Anxious and bewildered: The appeal of Jacinda Ardern

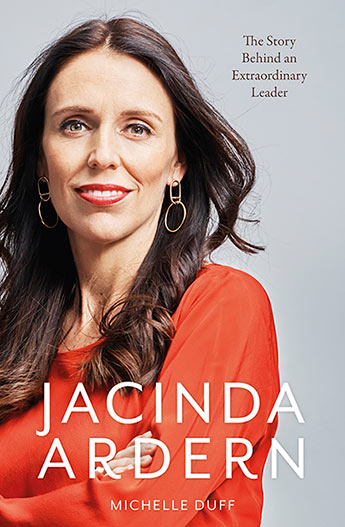

A good political biography is rare in New Zealand literature. Barry Gustafson’s acclaimed study of Michael Joseph Savage, ‘From the cradle to the grave’ (1988), is hard to beat. Rich with narrative, and backed by meticulous research, it makes for a compelling read. But most importantly: there is no hint of political bias or sensationalism. Gustafson, a former Labour candidate, approaches his subject with cool detachment. The result is an intimate yet critical account of a larger-than-life prime minister. Can the same be said of Michelle Duff’s new book, ‘Jacinda Ardern’?

Those wanting a behind-the-scenes account will be disappointed. Duff’s book is less political biography, more social commentary and personal memoir. But it does offer a fascinating insight into the sub-culture that gave rise to ‘Jacinda’. Duff obviously sees a reflection of herself in the Prime Minister. The book is really about their parallel lives: two young, middle-class Pākehā women from provincial New Zealand, struggling in a man’s world and troubled by the legacy of colonialism. If nothing else, Duff has captured Ardern’s symbolic meaning. To her supporters, she personifies all that is good about politics. At the heart of their belief system is an unyielding faith in humanity and the redemptive power of collective action. In short, there is no problem that cannot be solved by moral leadership. We see it in the Prime Minister’s rhetoric on climate change and the ‘Christchurch Call’.

British philosopher John Gray calls this humanistic philosophy ‘meliorism’. It is the idea that social progress, like scientific knowledge or technology, is real and cumulative. That is, our politics and morality are gradually evolving. Each generation is better than the last. Take, for example, the treatment of homosexuals in New Zealand. As a society we have come a long way since the 1960s, when sex between men was illegal. Now we have marriage equality and more tolerance of gender diversity. There may still be a long way to go but meliorism sees this progress as inevitable. Thus, we have come to view the expansion of personal autonomy and individual freedom as a universal law of civilisation. Sooner or later, all societies will get there. This is not just a political theory. For many, it is blind faith.

As Gray argues, the ‘inevitability’ of such progress is a delusion. What is gained in one generation can be lost in the next. The election of Donald J. Trump has probably set back the liberal progressive cause by decades. Over the Atlantic, Brexit has fatally undermined the European project. It is not clear that the damage can be undone. Yet, social justice activists and centre-left politicians cling to a belief that they are on the ‘right side of history’. The forward march of progress will resume – once the angry white masses have had their privilege checked. Ardern’s unlikely rise to power was the beacon of hope they were looking for in a world of Jordan Peterson and 4Chan. As Duff writes on page 82: “It felt, for a short, breathless moment, as though it wasn’t just Ardern who had won the election. It felt as though it was all of us.” Later in the book, reflecting on Ardern’s celebrated speech to the UN General Assembly in 2018, Duff recalls that it “finally felt like the good guys might win.”

And still there is nagging doubt throughout the book. Duff spends many pages wrestling with social and political realities that no feel-good speech can overcome. Citing the New Zealand Election Study, she is dismayed to learn that more Pākehā women voted for National (38%) than voted for Labour (30%) in 2017. For Duff, the most obvious explanation is that white women vote to protect white male power because they are dependent on white men. Presumably this logic would explain the ethnic and gender composition of Ardern’s Cabinet. Duff also laments the fact that our female prime ministers have all been “Pākehā, cis-gendered, able-bodied, straight”. The complexities of ‘intersectionality’ are further highlighted in Ardern’s callous treatment of former Greens co-leader Metiria Turei for admitting to historic benefit fraud. Turei’s only real crime, we are told, was to be poor and brown.

But Ardern’s status as a symbol of progress was affirmed when she became our first prime minister to give birth. This alone has brought gender equality much closer, according to Duff. “Individual women,” she writes, “are feeling empowered to demand rights they never felt entitled to.” Nevertheless, many inconvenient truths remain. Almost two hundred thousand children live in material hardship under Ardern. Some forty thousand people are homeless. And a lot of women still work in jobs that are grossly underpaid. Most New Zealanders profess a belief in fairness and equality. But few accept that colonialism and patriarchy are to blame for these injustices. Having so eloquently described what ‘Jacinda’ means to her, Duff leaves much to be desired. We end the book where it began. What makes Jacinda Ardern get out of bed?

Ardern represents a cosmopolitan liberal milieu that is increasingly anxious and bewildered. Her major success in 2017 was to renew faith in the progressive liberal cause. Duff’s book is a testament to this. However, it is less clear what Ardern makes of it all. Perhaps the most revealing quote in the book is from a 2014 NZ Herald interview in which Ardern discussed her religious background. She cited politics as a key reason for leaving the Mormon Church. “It’s faith of a different kind, isn’t it?” Ardern’s belief in the New Zealand Labour Party does have something of a religious quality. If Labour is the Church, she is the Messiah. Her victory in 2020 will depend on whether she can persuade her followers to ignore reality and keep the faith.

Ryan Potts is an avid book lover.

Maybe I’ll buy a copy for those insomniac moments in the early hours……

I’d recommend Roughan’s nauseating hagiography of Sir John for that. Unless you’re a fan, in which case you’ll probably spend most of your time wanking over it.

simonm so beautifully and succinctly worded. Johns book( he aint no Sir) is a wank fest!

I could find far more interesting things too ” wank over ” than this diatribe.

There is more to politically success than winning and staying in power. You have to change things for the better. Function before form.

On a side mote I don’t think society has improved morally (I know that article isn’t speaking to this directly). The same problem of how we treat people that think and act differently to us remains. In the 1960s it was homesexuals that were persecuted by the ‘moral majority’. Who falls into the groups may have changed, but I’m not convinced that the ‘them and us’ mentality has changed at all.

I agree with John Minto. https://thedailyblog.co.nz/2017/08/07/jacinda-washed-her-hands/

Ardern is a PM of convenience, selected not elected, and timeous for the hijab and tear moment followed by “we will ban” and “you will obey”.

She did a bit for the poor recently talking talk for the poor that didn’t check out. Her critics piled in on her. Strange woman. Mental duality. Passionate ‘old NZers’ can’t take her seriously. I include the Governor of the Reserve Bank.

The last generation of us who grew up in the Welfare State are fighting for democracy and she’s resisting. After us just power politics without justification. And thus no allegiance due — witness the increase in gang members.

I find her silly. Everything is in the hand of Helen Clark. A woman known for not breaking … from the establishment.

The elite all agin us, and we’re right. Easier to take here in NZ than America with Bernie. Hate how difficult it is to restore democracy. A ruling class who believe in meritocracy above all, their own merit by a truthful path(?!). If you don’t know the least you’re in the wrong here in NZ. Soul v. immediate reward.

Comments are closed.