The rain sheets weeping over Opotiki. Tears for a fallen chief. The kohu descends. I ran to cover, turned on the radio. Twitter. Ranginui Walker has died. He will stay in Auckland.

‘Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou Struggle Without End’ sits next to Nelson Mandela ‘Conversations with Myself’ on the shelf next to me. Ranginui is up there, with Bruce Jesson and Keith Sinclair and Colin James, the thinkers and historians and tellers of the New Zealand story. The handful of public intellectuals worth listening to or reading would always include Ranginui Walker.

Ranginui is a national treasure, respected kaumatua, rangatira, scholar, one of the few who refused to take a knighthood when the National government brought them back in, a gentleman, a hit with the ladies, all round top guy in everyones reckoning.. but I never really liked him. And he didn’t really like me. Maybe my contrarian trash talk in the student magazine wasn’t his cup of tea? He knew the dangers of writing columns. He was always controversial. Admirably so. Inspirationally so.

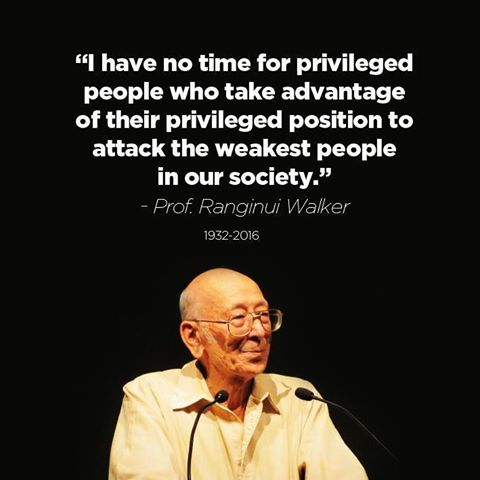

Saying upsetting things to smug audiences in the NZ Listener, Metro, radio, TV, lectures was simply what he did. As a professor at Auckland University – enjoying all the privileges of that European institution – he was afforded an impervious parapet to joust at the plebs. It was just delicious. He was perhaps how a Maori version of Malcolm X would have been if he had made it to middle age. Clear positioning, strident delivery.

He won a broadcasting complaint against the Top Marks show in the early 90s after those cretins became so furious with him they broadcast his address on air and encouraged Pakeha utu for whatever truth it was that they couldn’t handle. He may have been a prickly liberal, but he was loathed by the rednecks.

He is quite used to people not liking him. Not liking the subject may make this obituary a bit difficult, but no more so than dodging each other around trays of finger food at gatherings have been all this time. Seeing as he was into unflinching confrontation with the ignorant and a vivid account of the facts so this should be.

I never got to experience the warm and generous side of him that others have relayed. From my observations I found him to be a forceful and charismatic personality who didn’t suffer fools. A very sharp mind, a quick wit. At times ascerbic. A direct, Pakeha, way of presentation. Huge ego. Tough. He didn’t just want to spout he wanted to do something about it. He was a man of thought, a man of action. From all accounts his wife Deidre was instrumental in his operations. His clan now have enough degrees combined to start their own university so education must have been a strong priority for him.

Now he has passed. What are we to make of the man and his legacy?

Ranginui Walker fought for truth and justice, for Maori. He lived it his entire life. He grew up in the Waiaua valley east of Opotiki in the time of the first Labour government. That Opape block was designated an inalienable reservation at the time of his childhood, that safeguard was soon to be lost as the process of colonisation continued. He was old enough to have seen and heard the last survivors from the NZ government’s invasion and punitive occupation of the Whakatohea homeland of 1865. The experience of the invasion – Raupatu – that had reduced his tribe to obscurity and poverty was passed down first hand to his generation. Is it any wonder his sense of grevience was so palpable given the proximity to the eye witnesses to history.

He was a man for his time – Maori and Pakeha alike needed to hear the korero in the 1970s – and he was also a man of his time in the sense his ambition and expectations of Pakeha and the New Zealand regime and how to end it, achieve Tino Rangatiratanga and get the land back was a conventional acceptance of social pressure leading to gradual reform from within government. He used the tools of the Crown, such as the artifice of the Maori Council to secure victories. He was shrewd. He was at home in the halls of academe. Was this limiting, was this radical? Was Ranginui a necessary stage in the NZ story – a late colonial era messenger – a harbinger of the close of NZ and the beginning of Aotearoa?

I think Pakeha loved him more than Maori, certainly from the reactions on social media it would seem so. These include Pakeha who get his name wrong and edit books on NZ without including Maori and so on, so it is difficult to say how much genuine impact on Pakeha he had in practice. Certainly Maori had great respect for him and reverence, although his book on Whakatohea was polemical and self-serving which irked many from his tribe.

The Pakeha who hated him for addressing racism also loved to hate him. They needed to hear it, for the first time they were hearing it, and they didn’t like it. He was polarising. It was great sport in the contest for a nation. His analysis was cutting.

As a text on decolonisation however his great book offers bleak hope for radical change: only 500 more years of continued colonisation was my take-away. He writes from his position as having grown up in a totally colonised situation where the answers to his people’s predicament is not apparent in the existing literature. He had to write that literature for us.

The last time I saw him was down the road at Ohui Domain at the 150th commemoration of the battle of Te Tarata last year. He looked very KGB in black outfit and hat. Svelte/sinister. Resembling a Maori Monty Burns, he stalked briskly about. I chatted to his son Michael – like his father also a professor – outside the tent. We laughed – he’d made his way straight to the pae. He would lecture Treaty Negotiations Minister Christopher Finlayson across the confiscated whenua. He would rebuke the Crown party with facts, disarm them with logic. He would coolly dissemble the colonial apparatus. Chronologically. The brutal reality, generations dispossessed. And the Ministers, on behalf of New Zealand, would have to sit there and suck it up. Classic Walker. We loved it.

He said that Treaty relations would resolve themselves in the bedrooms of the nation. This was quite a famous quote I am paraphrasing and it suited the time of the 1980s and early 90s to repeat it. It was glib, sure, but it carried the caché of Ranginui’s mana and was considered incisive and definitive on the subject. It seemed to be self-evident that the proportion of Maori would increase at the time when the Maori population was growing. But not now after 30 years of mass migration. The tendency to gloat about the fall in Pakeha population and to lump the non-Europeans up as if that was supposed to be axiomatically beneficial to Maori or indicative of Maori influence should be put away too. These things aren’t true anymore. The colonisation juggernaught has skittled those comforting projections. Ironic to have heard him maintain these outdated lines that conceal the facts – all of which he would have railed against had he identified the fault in his opponent. The scenario of reverse assimilation presumed by many to be inevitable whereby Maori and Pakeha inter-marry and thus the majority of the population will end up with Maori whakapapa is weakening by the day. After the 1987 Immigration Act the immigrants coming in have now outnumbered the total Maori population, and any ‘bedroom solution’ is ever more distantly postponed. To discover the government’s chief cheerleader for immigration and the go-to official population expert, Paul Spoonley, was close to Ranginui was interesting. Both seemed eerily complacent on this front.

Ranginui has seen much in his long life and wrote and made history. He was around at the time New Zealand still used Stirling, he was around when John Key tried to change the flag. He saw so much change that it is tempting to think he had seen it all and that a Maori renaissance had already peaked when really there is so much of the journey yet to go. He declared in his book (1990) that we were in the post colonial era. I’m sceptical of that, it doesn’t appear so, it runs counter to the notion of struggle he outlined.

He won’t see in the Raupatu Treaty settlement that has eluded Whakatohea since the initial aborted foray into direct negotiations with Doug Graham in the 1990s. It has left the tribe relatively landless and without funds, having to borrow. The farcical mandate process is being shoe-horned in by TPK this month against challenges. He never made it to see that saga to a conclusion though he gave every impression he was behind the manoevrings of the trust board Hapu involved to get a quick mandate and settlement sooner rather than later.

He hasn’t seen his protegé Mihi Forbes’ report on Maori content on RNZ and what breaching the walls of that notoriously euro-centric bastion would look like. He won’t ever hear a Maori on a prime time show on Radio New Zealand. (Will we ever?)

He acurately predicted he would never see out the endless struggle he wrote about.

Maybe with this great man’s passing Maori and Pakeha will emerge from under his shadow and find a way to think about how the struggle will be won sooner than 500 years.

We are constantly poorer when we lose a great, but that is part of life, new greats will be born. We will however be far poorer as a nation if we forget Ranginui’s words and works. A life well lived.

He never seemed like 83 to me, the whole country is poorer for his absence, not just Maori

Indeed, Rae.

Ranginui Walker bridged the gap between Maori and Pakeha worlds, allowing us to move forward and better our understanding of each other. He may have said things at times that Pakeha did not want to hear – but they were things that needed to be said.

Walker was also opposed to immigration policy changes 1986/1991

http://www.waikato.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/74141/dp-37.pdf

Comments are closed.