When the smoke from the Australian bushfires turned the sky yellow at the beginning of the year, it felt like shit got real. Armageddon was upon us.

Koalas, iconic as cuddly charismatic megafauna as they get, innocents, caught burning on fences, screamed as fires raged. Bodies of Australia’s quirky animals, found nowhere else on the planet, lined highways dead. Rescue efforts were inadequate in the face of inferno – fueled by poor forest, land and political management, drought, arson, ecology and the effects of climate change. It was hard to comprehend, or to emotionally accommodate, the immensity of the fires and their damage, (a billion animals killed), though the impacts of ad hoc and systematic anthropocentric actions were on display. (We did this). The scale of harm and damage and death was hard to comprehend, but so utterly unsurprising. Social and online media feeds were full of photos of the sky – which was visible outside without the posts, and reflected a collective struggle to reckon with the evidence and scale of interplanetary change that’s been accelerating since the industrial revolution and especially since the Second World War.

Then the American targeting of Iranian General Soleimani and the Iranian downing of the Ukrainian plane shook our fragile sense of international security again. What a disturbing start to the year and the decade. Last year the Doomsday clock was at two minutes to midnight, and now it’s at 100 seconds to go.

But that’s all yesterday’s news now, though the fires still rage, because the novel coronavirus is the highlight of today’s media moment. Epidemics sell news and advertising, as well as hand sanitiser and facemasks, though meat exports and tourism may suffer.

Most of us are back at work now, and school returns over the next few weeks. We sink back into our lives with the start of the economic year. Holidays are almost done, and the abnormal destruction over summer, sinks into the background, becomes a complacent, new normal. There are more pressing issues to consider – work, school, deadlines, traffic jams, the Government’s road building announcements, the date of the coming election.

Almost half a billion dollars has been donated for bushfire recovery. But anti-Chinese sentiment has been an ugly reaction to the coronavirus. Our best and worst selves have been on display.

In Australia, fires still burn. Land and forests continue to be cleared for roads, farms, timber and coal mines. Kangaroos are still ‘culled’, and koalas are killed as business as usual. (Today I see photos on Facebook of up to sixty koalas left dead and dying after a bluegum plantation was felled in Victoria) Political certainties continue to unravel. The Brexit process takes another step towards the new unilateral political order.

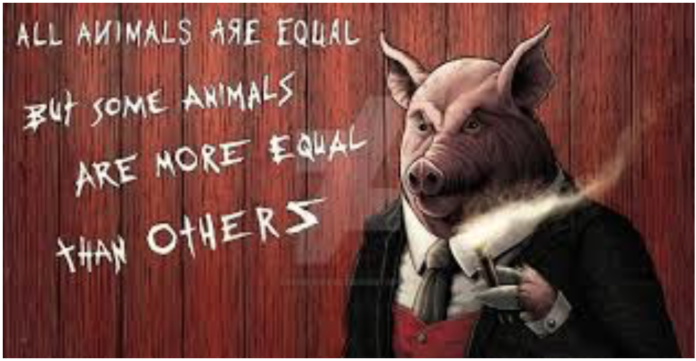

It’s been hard not to feel despondent at the damage we’re doing to our beautiful world. And meanwhile I think of the pigs. Because while at least the short media and public attention span has been on the impacts of impulsive, provocative and reactionary political leaders and the consequences of industrialisation on ecology and wildlife, entrenched abuses to farmed animals and nature mostly go unacknowledged.

If you were a pig, not a human, chances are you’d never see the sky. You might never feel the earth. You’d never be free. Your last moments would be in a slaughter house, filled with fear. While we all empathised deeply with burnt koalas and injured kangaroos, few give a thought to the lives of animals used for meat, who live far removed from natural habitats, enslaved for the human palate. It’s unconscionable what we inflict upon wild nature, but at least koalas live free.

70 billion animals are treated as economic units in farming systems around the world every year, and about 50 million of them are in intensive farms. They’re crammed so tightly to minimise costs that they are denied natural habits, habitats, social relations and lives. A pig is as smart as a dog, but society would be outraged if you treated a dog the way we treat millions of pigs. Intensive farming creates its own negative feedback loops – in polluted rivers and aquifers, in public health legacies (cancers, obesity and other diseases), in animal welfare sacrifices, and human and animal epidemics, causing the waste of animal lives as in responses to Mycoplasma Bovis, (hundreds of thousands of additional cows ‘culled’, on top of the approximately four million killed per annum in New Zealand as part of usual business), and the African Swine Fever – where across the world, millions of pigs are buried alive.

Western outrage to the conditions of the Wuhan meat market, selling wild animals from bats to koalas to wolves, is right in part. Xenophobic and racist responses are distasteful, and consistency would require a critique of our own methods for deriving meat and eating pleasure. Korean and Chinese dog eating festivals provoke the same western outrage. But double standards abound. It’s wrong to eat dogs, but ok to eat pigs. It’s wrong to eat or kill koalas, but ok to eat age old wild living fish – in fact, that’s sport.

The Biophilia hypothesis suggests we’re hardwired to care for soft, (young), big eyed animals, that our love for nature is an evolutionarily important element of human survival. And who would deny that koalas are cute? It’s been argued that the ‘cuter’ the animal, the more chance it has of being a conservation priority. There’s a risk of overstating that though – because – koalas (extinct by 2050?), Maui and Hector’s dolphins (around 57 Maui left, and some Hector’s sub-populations down to the 40s), even though there are none cuter. Lions, tigers, elephants, all the supposedly hot megafauna, dwindling despite our innate preferences for the furry, big eyed and cute…

Concerns about climate change and the treatment of wild animals are rhetorical hypocrisy and will fail our compassionate and humane potential if we don’t change the way we do things, the way we live, what we eat, how we treat the natural and living world.

But on a finite, interconnected, sensitive and dynamic planet, it’s clearer than ever, that if we don’t change what we’re doing, (the road to nowhere), we’ll head up where we’re going. That includes how we treat animals in the wild, as well as in farms.

So next time you think about koalas, think about pigs. And next time you think about bacon, think about pigs. And when you head off to work or complain about being stuck in traffic, think, what if you were a non-human animal; what if you were a pig? A change to humanity can start with what’s on your plate.

If you were a pig you wouldn’t want to live in PRC-controlled territory 🙂

Or in any factory farm anywhere in the world, including New Zealand

You’re probably correct in some way I just can’t help but clap back. Yknow dehumanising people has a greater destructive value than pushing human virtue into pigs. If animals truely do have human traits then under those circumstances humans can be discarded just as easily.

Deep but very true Sam

Christine i despair too at the way we cannibalise our natural world and the creatures who live alongside us.

Along with the climate destruction we are all responsible for we are determined to erase all living creatures in our pursuit of greed , comfort and excessive consumerism.

Very few people respect or are in tune with the natural world and the special relationship we should be protecting.

Humans remain the biggest threat too all animals and environments and the idea we are the smartest of all the life on earth is an oxymoron if you look at the way that intelligence is decimating our very existence and that of the living creatures who deserve the same rights as we have given ourselves.

I don’t know the answer in trying too change the current mentality but things are changing but not fast enough.

What we are doing too our natural world and the creatures who inhabit it must become central too the way we approach everything we do and that has too enter our conscience and become a priority in all of the things we do in our lives.

A sobering post but we need more like this too challenge the status quo.

Much appreciated Christine.

Environmental Ethics. Deep Ecology.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byQ86TjwCEQ

System Change. Now.

Stingrays or Mantra Rays might be even less attractive than pigs, and even less likely to ever try to communicate with a human, you’d think.

But here’s a vid of a Mantra Ray asking a diver to help remove some fishhooks, and waiting while he does so.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKPnFt90gEI (From last July)

We are by definition predators and masterful ones. That said I agree with your point about treating animals with more respect and not being as wasteful and destructive or cruel.

I used to hunt and if I’m being honest if the world ended tomorrow I would again but as my dad taught me you kill quickly and you never let anything suffer.

Very clear “Cheers! Thanks, guys!” message from a big old fella after the baby was rescued from a ditch. It’s well worth the 3 min wait through the vid. while they dig him out. Wild Elephants Salute Men Who Rescue Their Baby

“If you were a pig.”

You would be very weary of David Cameron hanging around?”

@ DP.

Ba hahha ahaha ahaha ahahah….

What if this particular existence was one of many?

Our entire Universe ‘as we know it’ is a single organism and part of an even greater organism?

And we can only see an unimaginably small part of it, and the farthest we can see is already millions and billions of years old anyway.

What of this particular reality was a post in an infinitely long fence?

The thing that intrigues me is the anomaly that is the collective ‘we’ are ‘here’ at all.

If our ‘energy’ wasn’t progressive and multidimensionally travelling?

What if we were born, as some believe, from a mystical conception to have one, often a bit shit life, then disappear into a void?

The answer’s simple isn’t it? We couldn’t be here to disappear so there goes that idea. Sorry, evangelist nutters. The fact that we’re here at all sets a precedence and I don’t think the precedence was set by a few scrawny, overly made up old ‘merican women or fat, creepy guys in polyester suits with terrible hair bashing bibles.

So? Why are we ‘here’ then? What explanation does any of us have?

What’s clear to me is that we’re on the move. We’re born, we gather about us our bones the meat and tendons to enable us to function then we head out the door … Why?

We’re quite complex organic machines refined by many iterations throughout evolution to best function for as long as possible given the reletavily frail nature of the architecture. A beetle can fall off the roof then run off. Could you?

But why?

I think it’s a learning and evolving thing.

As our ‘energy’ is born into exoskeletal meat and bones the new ‘We’ are off, yet again, to almost unknowingly accumulate as much information and experience as we can before our carcass dies underneath us. Like when the lawn mower blows up. Or breaks down. I’m never sure which it does?

So, it’s probably not a ‘good’ thing to do? To eat our fellow travellers?

It’s also probably not a great thing to race them, enslave then, prune them, preen them, dress them up in frocks and call them Fi Fi? Nor to bravely fight them in the distress we place them in for our visceral pleasures derived from seeing a grown man in tights stick a pointy thing into a fellow traveller? I don’t think that’s so flash, to be honest.

Imagine being in a plane and the person in the seat next looked delicious. And they knew you thought that and they knew they were your prey and they knew you’ll eat them the moment you get off your flight? What conversations might you then have during the flight? Would you ask them what their diet has been up to this point as you lick your lips? Would they, as your prey, be, in some way, compelled to tell you?

Have I just described our human/animal relationships?

We, all of ‘us’, are cohabiting on a hurtling biosphere but we humans eat our fellow passengers. How charming.

? One would a thought that we’d have evolved beyond that wouldn’t you? Maybe next time a-round…?

Comments are closed.