Summary of the June, 207, CTU Economic Bulletin

The share of income that working people receive from all the income generated by their work – the labour income share – is important for many reasons and has long been of interest. It is a

measure of income inequality because the richest people in the country tend to make most of their money from “unearned” income from wealth such as dividends, interest and capital gain rather than work – the capital income share. If the labour income share is falling it can mean that wages are not keeping up with rising productivity. It is also a way to compare wages (and the cost of labour to employers) between countries. New Zealand’s labour income share fell steeply after the 1980s – one of the sharpest falls in the OECD. The share going to wages and salaries is low compared to most other OECD countries.

Current official data goes back to 1972. What happened before then and how it has changed over our history. Has New Zealand’s labour income share always been low? Other income inequality measures show high inequality in the early part of the 20th century, falling during the 1940s and 50s with the welfare state, stronger unionism and collective bargaining and progressive tax systems, but rising back to high levels since the 1980s. Is the labour income

share similar?

In short, there was a rise in the income share for wage and salary earners between the 1940s and 1970s and a steep fall from the early 1980s. The fall resulted from a combination of wage freezes, radical restructuring of the economy and the state, deregulation and individualisation of employment relationships and deunionisation. It brought the labour share far below the OECD median and comparable economies.

Part of the reason for the pre-1970s rise was the fall in self-employment (dominated by farming), many becoming employees. By 2016, the self-employed had their lowest share of income since 1939. The largest beneficiary was corporate profits which rose to a 19 percent share in 2016, a level reached before only in 1940 under wartime conditions.

Labour productivity and real wages (wages after taking account of inflation) appear to have been closely in sync only during the period 1947 to 1974 when New Zealand’s industrial conciliation and arbitration system of collective bargaining extended by awards was working relatively well. From about 1990, under the deregulated employment conditions resulting from the Employment Contracts Act 1991, real wage growth fell behind productivity growth.

The only period in which labour’s share increased relative to capital, was the period from the late 30s to the 1970s. This is not the result of Labour’s policies such as the welfare state, but of the return to profit of international capital resulting from the state restructuring of capital coming out of the depression and World War 11, both of which destroyed massive capital and created the conditions for a new cycle of capital accumulation – the post-war boom.

With the end of the post-war boom as the Tendency for the Rape of Profit to Fall caused a crisis of overproduction, falling profits meant that the wage share had to fall. Thus there is no such thing as a ‘fair share’ of wages vs profit, only the class struggle over the share of value produced by labour.

Ken Douglas head of the CTU around the time of the Employment Contracts Act of 1992, notoriously justified the fall in the share of labour to capital as the division between labour and capital of new productivity, as if capital is productive and deserves a share.

But capital is not productive. All productivity comes from labour. Not only the living labour that produces new wealth, but the stock of expropriated past generations of dead labour accumulated as wealth in the hands of the capitalists that is invested in new technology.

Taken back to basics, labour productivity is the same thing as the rate of exploitation = s/v. Surplus value is that which is expropriated as the source of profit. Variable capital is the value of the wage or of labour-power measured as ‘socially necessary labour time.’ Increasing the rate of exploitation in a period of capital accumulation can cause both actual profits and real wages increase. But that also depends on the class struggle or the balance of power between labour and capital to divide the share of value.

Talking about sharing productivity is therefore a giant con trick which represents capital’s projection of its own class interests masking the origins of its profits as expropriated labour. It is premised on the myth that capitalist growth is permanent and that rising productivity allows both wages and profits to rise like competing yachts on foils.

The share of self-employed suffers the same fate or declining share in income. It is subject to the same laws which govern capitalist accumulation and the cycles of booms and busts. That is because the labour of self employed is a form of disguised wage labour hiding behind contract law. Most self-employed are ex-wage workers who were made redundant in the 80s and 90s as a result of the Rogernomics restructuring. They don’t work for productive capitalists but for the banks from which they borrow to buy their tools of trade. But as contractors and sub-contractors their income is squeezed down by big capital, which explains the phenomenal short life of most small businesses.

All of this proves that income shares are not the result of government policy but the capitalist cycle of expansion and decline of profits which determines the rate of exploitation of labour in the last instance, and also the relative power of labour and capital in the class struggle to determine income shares from the same value produced by the working class.

The biggest factor in worker’s lives is their pay!! When the Contracts Act started, workers lost pay and work conditions to the point where their lives were completely changed.

They lost wages.

They lost overtime.

They lost tea breaks etc.

They lost regular hours of work.

They lost time to be with family as they tried to find extra hours of work.

They lost the ability to be club members of sports and recreational things because they were now cash and time poor.

Substance abuse and violence escalated.

People sold assets to survive.

People dropped insurances.

People stopped saving and started borrowing (credit card use)

Now we have inequality at inhuman levels.

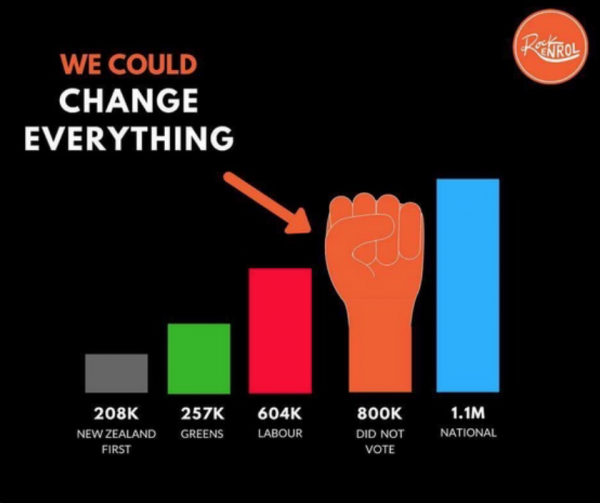

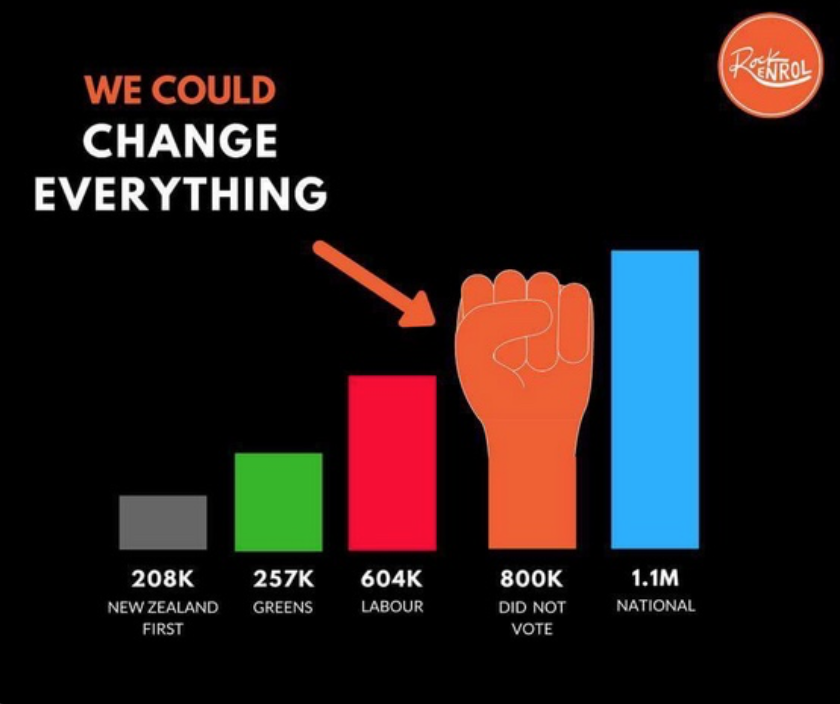

So we have suicides, violence, lawlessness, and political disengagement.

So, I don’t agree with your summary paragraph at the end of your article. Democracy is not related to wealth cycles. Wealth cycles only impact on people if their share of working wealth is deliberately undervalued by those who wish to clip the ticket on the way.

Currently in NZ we have a system which barely rewards the work, with the resulting injuries to society. Also productivity is low as there are few incentives for workers to strive, as they are in survival mode.

Change the level of reward and conditions for work and enterprise, and improvements will follow.

Comments are closed.