With no tsunami and not much Coronavirus to report this week, the media has been dominated by the gore and horror of Court reports.

Media headlines would indicate we live in a bloody and violent society. In recent weeks, trials have been held for a man who shot an alleged drug dealer colleague in the head from behind (“in self-defence”), then chopped off his legs with a chainsaw and stashed him in a deep freeze he’d bought for the purpose. Meanwhile he went on a Tinder date and took his son out for dinner. Elsewhere, a trial is being held where a street fight turned extra nasty, and a man died after he was struck several times with a wood-splitter. In another trial a meth addict bashed his friend to death with a cricket bat. A man killed his partner and the mother of his baby in a violent rage.

With all the spectacle, barbarism and unfolding drama it feels like ringside seat at the Colosseum. It’s all stompings, smashings, gunshots, bodies discarded in the bush, hidden in car boots, abandoned, while loved ones despair. Behind the headlines these are real people, perpetrators, victims, families. This is real individual and social harm.

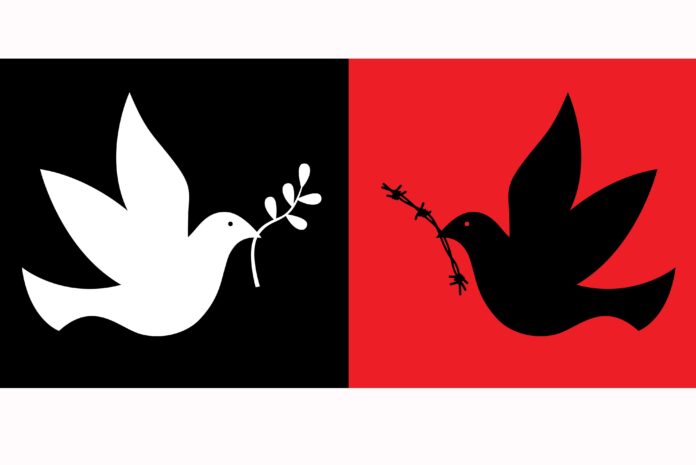

Those left behind, and wider society look for justice. But whose justice? And justice for whom? The Stuff Homicide Report highlights links between socio-economic deprivation, drugs and alcohol, family violence, and historical and contemporary violence and crime. The prevailing binary narratives of victims and villains, of good and evil, bely the many degrees of crime and criminality and oversimplify the questions of culpability and guilt. There are so many victims in a violent society, it’s hard to know what justice looks like, much less how it might prevail.

Much is rightly made of the fact that the justice system is racist. Not (colour) blind at all, it’s stacked against generations of young Maori and Pasifika, who are overrepresented in jails, but underrepresented in the judiciary – in both its personification and its system. It’s a punitive model that gives effect to society’s urge for revenge and punishment, but does little to heal, restore or prevent. Convicts say that they become so institutionalised that when time for parole review comes round, they feel ‘gate fever’ and sabotage their chances of release so they can stay inside. Jail doesn’t prevent prisoner access to drugs, gangs, violence or crime. It seldom provides redress to harm. Victims of crime and their families may never recover.

Our desire for retribution is strong, but there are no winners even when the most heinous killers are ‘locked up and we’ve thrown away the key’. We have one of the highest imprisonment rates in the world – higher than western and eastern Europe, and in the ranks of punitive countries such as the US and Iran. We have disproportionate rates of imprisonment for property, violence and sexual crimes. Recidivist rates are also high. There’s evidence of mistreatment of prisoners – solitary confinement that breaches UN standards, neglect of prisoners suffering from cancer, suicidal tendencies or other pathologies. If they, and our society didn’t have pathologies to start with, they probably wouldn’t be there, but prison doesn’t seem to help.

At the end of last year there were 8,500–9,500 people in prison, 3000 of them on remand – as yet unconvicted of any crimes. 52% were Maori though they make up about 16.7% of the NZ population, and 32% were European. 11.5% were Pasifika, and 4.5% other ethnicities including ‘Asian’. 6.6%, a growing proportion, of the prison population are women, and 1.4% are juveniles. In addition to the victims of crime, and the victimhood of the criminals themselves, there are 23,000 children with at least one parent in prison. Many of these children may maybe living in the cycle of violence, poverty and deprivation too. When Al Jazeera interviewed a young Gisborne boy Sirius in an expose of crime and punishment in New Zealand, Sirius’ ambition was to go to jail so he could see his dad. In jail, and with fellow criminals and outcasts, many find the family they never had.

So while I see news reports fuelled by violence; facts reflecting the violent fiction that fills mainstream media entertainment, I see a system that fails the innocents in our society – as it fails those who are part of intergenerational violence and criminalisation. I see a system that doesn’t seem to prevent crime, as the threat and reality of prison is an inadequate deterrent. I see a judicial system that is unequal in its distribution of costs, a wider system that sensationalises and normalises violence, that lays its sentiments on people of white skin, and prejudices those without; That lays criminal ‘justice’ on socio-economic injustice and inequity; That looks for punishment not redemption. It’s a system that takes a simplistic approach to addressing the effects of crime but invests too little in its causes (including drug laws and addiction treatment). But it reflects society’s lust for vengeance, security, a villain to hold to account. And certainly, people should be held to account.

Grace Virtue was a ninety year old, a kindly grandmother who let three fourteen and fifteen year old girls into her house to use the toilet. They punched her in the face and stole her money to buy smokes and lollipops. The girls were recently sentenced to two and a half years in prison, and home detention. Mrs Virtue’s son said ‘”There are no winners. We are all losers and the biggest loser is Mum … it all seems so pathetic.” Victim’s families, the UN and the NZ Minister of Justice agree the system is broken. But it fills vacant slots in the news.