Three types of money are in existence – Gold, credit money and token money

Monetary policies are run by the Central Banks, with the US Federal Reserve operating like the world’s central bank. Their principal tools are setting certain interest rates they can control or influence and creating or reducing the supply of token money. But token money is only one type of money in existence today.

To understand what is happening we need to understand the interaction of three types of money in existence today – token money, credit money and gold. Gold which is a product of human labour has emerged as the universal equivalent of all other commodities as a measure of value. All societies with a developed system of commodity production and exchange need a universal equivalent to function. Gold can also be hoarded for its intrinsic value, especially in times of monetary disorder.

Gold does not disappear in a crisis. It always retains its value through any crisis. Capitalists and central banks hold a portion of their wealth or reserves in gold because of these special properties.

The second form of money is token money issued by the state, dubbed “fiat” money by economists. So long as the currency is not “over-issued” relative to the existing quantity of gold, the currency – whether it be dollars, pounds, yen, or rupees – can retain its value so long as it is backed up by a state power which can impose taxes and use force on those it wants to do its bidding.

But if the currencies are “over-issued,” they lose value in proportion to the over-issue. In normal circumstances, a doubling of token currency will result in a halving of its individual value. In other words, the currency price of gold will double. This is the origin of general price inflation we saw during the 1970s and early 1980s. Then US President Richard Nixon declared “We are all Keynesians now” and believed he could finance the Vietnam War without massive cutbacks in social spending in the US through budget deficit spending. The inevitable result was a steady devaluation of the US and other currencies and endemic inflation worldwide.

The first casualty of this policy was for the US dollar to cut its link to gold at $35 an ounce in 1971. Keynes and Friedman claimed that policymakers would then be “free” of the gold “shackle” as it was dubbed by opponents of the gold standard. However, being free of the shackle only encouraged further devaluation. The price of gold hit $120 an ounce in 1976. Soon we had “Stagflation” inflation and economic stagnation at the same time. By the late 1970s, there was a flight out of the US dollar into gold that saw the “price” of gold soar to nearly $600 an ounce.

The progressive devaluation of token money is reflected in the virtually constant increase in the “price” of gold in US dollars since going off the gold standard in 1973

To prevent a total collapse of the currency, the US Federal Reserve had to stop further accelerating the rate of growth of the dollar it created, which, in turn, boosted interest rates to record levels of 20% for the Federal Funds Rate and drove the country into a deep recession. Bad as inflation was – especially for real wages of the working class, which was being paid in debased currency – from the viewpoint of the capitalist economy the worst result was this rise in the rate of interest which wiped out the profit of enterprise. Inflation dropped from 14.8% in March 1980 to 3% by 1983. By the mid-1990s gold stabilised for a period at around $400 an ounce.

The amount of token money that can be issued is governed by the total amount of gold bullion in existence in the world. This usually expands at a relatively steady pace of, say, 2% a year, so it is a relatively safe bet that token money can also be increased proportionately. But gold production also has its own cycle which runs counter to the normal industrial cycle and impacts interest rates and places objective limits on token money and credit creation.

If there were no objective limits to the creation of token and credit money there would never be a crisis of generalized overproduction every ten years or so like we have seen throughout the 150-year history of developed capitalism.

These crises have been analysed and explained by Karl Marx as being generalised crises of overproduction relative to the ability of the market to absorb these commodities at prices that guarantee the producer at least the average rate of profit. Overproduction is reflected in growing inventories, factory shutdowns, and unemployed workers. If token money or credit could be expanded at will forever, then there could be no such crises. That is why pro-capitalist economic writers can’t explain why they happen.

Monetarists don’t understand the different forms of money. They treat gold, credit money, and token money as essentially the same. Keynesians also don’t understand the different forms of money and why gold retains its essential role as a measure of value in economic life. Both Keynes and Friedman predicted that the price of gold would collapse once the state was stopped from being able to exchange their currencies at a fixed rate for gold. Of course, the opposite has happened, as Marx predicted it would.

Monetary authorities don’t understand the exact total of token money they can issue without devaluation. They operate to a great degree on trial and error. They don’t know what they are measuring the currency against, but the consequences of over-issuing become apparent very quickly in a rising price of gold, a broader leap in commodity prices in terms of the devalued currency and then a general rise in prices. This forces the central bank to increase interest rates, cut back on the currency being issued, or purchase previously issued currency to neutralise it. Failure to take action can lead in some extreme circumstances to hyperinflation and a currency collapse.

Credit money

The third form of money is credit money. Under a developed system of finance and credit, this credit money is created and centralised by the banks through making loans. They can use deposits of token money created by the central bank as a base from which to expand lending many times over the actual sums deposited amounts of customer deposits. So long as everyone doesn’t want their money back at the same time the merry-go-round can continue. This is called fractional reserve banking.

But banks are profit-making competitive businesses. They have a built-in tendency to seek more and more creative ways to create and extend credit to maximise their returns. Derivatives that serve as a kind of insurance against loans going bad are the latest example of that. Eventually, as inventories of unsold commodities pile up and credit tightens a breakdown happens, which will begin at the weakest links of the credit chain. A credit crisis and collapse of at least the most over-extended institutions then follow.

Credit money is not “real” money like gold and can disappear completely without a trace. The over-issuance of credit must be periodically neutralised for the system to restore balance. If there is no reduction in credit money then it is essentially being converted into token money. This will fuel an inflationary surge sooner rather than later with the inevitable consequences of a spike in interest rates leading to a deeper credit contraction, the very thing that conversion of credit money into token money is designed to avoid.

In the current crisis, the Federal Reserve has been forced to prop up bank deposits as the currency system is threatened on one side while staving off the collapse of the dollar-centred international monetary system on the other. These are contradictory goals.

The point of capitalism’s recurrent crises is to bring aggregate market prices back into line with aggregate values. Before a crisis hits, prices have inevitably been inflated by leverage. Before 1971, crises took the form of price deflation. Since the decoupling with gold, currency prices can increase, but capital still gets devalued in terms of “gold prices” as the currency itself depreciates. The 2007/08 debt deleveraging was short-lived, as the ruling class bailed itself out and passed austerity onto everyone else. The debt bubble and the discrepancy between aggregate market prices and aggregate values, however, remained and grew.

Law of value operates through the “Invisible hand”

There are laws that capitalism must obey. The first great economic thinkers associated with the birth of this system were Adam Smith and David Ricardo. They explained how the system worked. Smith coined the term the “invisible hand”. As the pro-capitalist site Investopedia explains: “The invisible hand is a metaphor for the unseen forces that move the free market economy. Through individual self-interest and freedom of production as well as consumption, the best interests of society, as a whole, are fulfilled. The constant interplay of individual pressures on market supply and demand causes the natural movement of prices and the flow of trade.”

This invisible hand is based on the law of labour value that Smith and Ricardo both accepted and that Karl Marx incorporated into his writings and took to their final, most scientifically developed form. Marx showed in “Capital” that prices (exchange values) are the form that labour values take. But as always there’s a contradiction between appearance and essence. Aggregate market prices can diverge from aggregate labour values (or at least what they would be if they accurately represented labour values). During a boom, prices drift above values.

Marx corrected the classical labour theory of value to show that a commodity’s price did not oscillate around a “natural price” based upon actual labour time but around a “price of production” that took account of the ratio of labour and capital relative to the average, and the turnover time. An individual commodity goes to the market to see what claim it can make on society’s finite amount of labour time. In total, aggregate values equal aggregate production prices. However, the credit system divorces the act of purchasing from the act of paying.

Lenders can lend more than they have – they leverage. This pushes up aggregate market prices above their respective countries’ labour values. Claims are being made on future labour time that may never be realised. In a boom, everything appears to be going swell, and leverage continues to increase until the “Minsky Moment” – a sudden collapse in value and some lenders start to panic that they may not get their money back.

We then get credit crunch, financial crisis, and recession. The law of value acts. Marx’s theory, contrary to myth, fully integrates the market, as the value of a commodity cannot be known until it comes to the market. That is, it isn’t the actual amount of labour time inherent in the commodity that gives it value, but rather the amount of society’s finite labour time it can claim in the marketplace.

When there was a gold standard, that meant deflation followed inflation. Now currencies (token money) get devalued (as measured by gold). Thus the stagflationary 70’s still saw prices fall as measured by weights of gold. Before fiat money, the devaluation was obvious in price deflation. With fiat money, we get currency devaluation, as in the 1970s, 2008, and again today. In all three periods, currency prices in gold rocketed. In “gold price” terms there was deflation. And the reason gold still features in financial markets is that it takes a certain amount of labour time to produce an ounce of it. It is still a measure of value, as distorted as it may be due to speculation.

With Marx’s theory of value (not the same as the classical labour theory of value), you have an objective theory of the business cycle based upon the excessive creation of credit money leveraging aggregate prices above their value equivalent (the market extended by debt), that results eventually in a credit-crunch, financial crisis and recession.

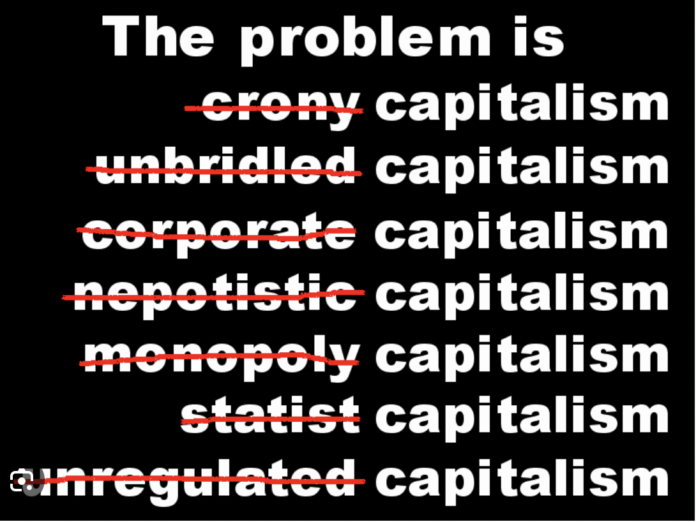

Pro-capitalist economists who run Central Bank and government policies can’t understand capitalism’s recurrent crises when they have the wrong, subjective, marginalist theory of value. Price and value are always equal in marginalist theory. With the wrong theory of value (marginalism), you have the wrong theory of prices; the wrong theory of money, and you can’t even build an objective theory of the business cycle (hence Keynesians blame the ‘poor animal spirits’ and monetarists blame central bank mismanagement). Whatever policy is used it can’t fix capitalism’s recurrent crises. At best it can delay them or moderate their impact at the cost of creating even bigger crises down the road.

Right-wing Mike wants more migration to price Kiwis out of housing and suppress their wages. Don’t be like Right-wing Mike.

The still “temporarily closed” gold window at the Fed, if reopened after fifty years, would now have to pay out gold bullion at a rate of almost $80,000 per Oz. — based on the M1 level of issued (paper) dollar currency, divided by the current gold reserves in Ft. Knox. The value was supposed to be fixed by the Coinage Act at $19.39 per Oz., before the dollar was eventually devalued to $35 per Oz., until Nixon closed the window.

The gold markets have long been manipulated to prevent the dollar-gold exchange rate from tanking this badly, in order to prop up dollar confidence. Paper contracts in gold — which set the gold price — are now issued well in excess of actual bullion reserves (currently about 3½-to-one, and at one stage 16-to-one), meaning a “bank run on gold” is now possible at the Comex. and Loco London exchanges. This means at some point there will likely be another Gold Pool Collapse, as happened in London in March 1968.

Gold is a mineral of surprisingly great abundance.

Limiting access to gold is what gives gold most of its value.

Is atmospheric carbon not the new regulator of prosperity.

Yes the private central banking rort has been exposed on many occasions….

Everyone who has attempted to interfere with it….dies…remarkable!

Comments are closed.