The panel on a sustainable world at the hui in October 2018 on What an Alternative and Progressive Trade Strategy for New Zealand argued for major changes to address pressing environmental issues. Economist Geoff Bertram explained how a trade strategy could help to address climate change.

Geoff is a Senior Associate Institute for Governance and Policy Studies Victoria University of Wellington and has written extensively on climate change, macro-economics and regulation.

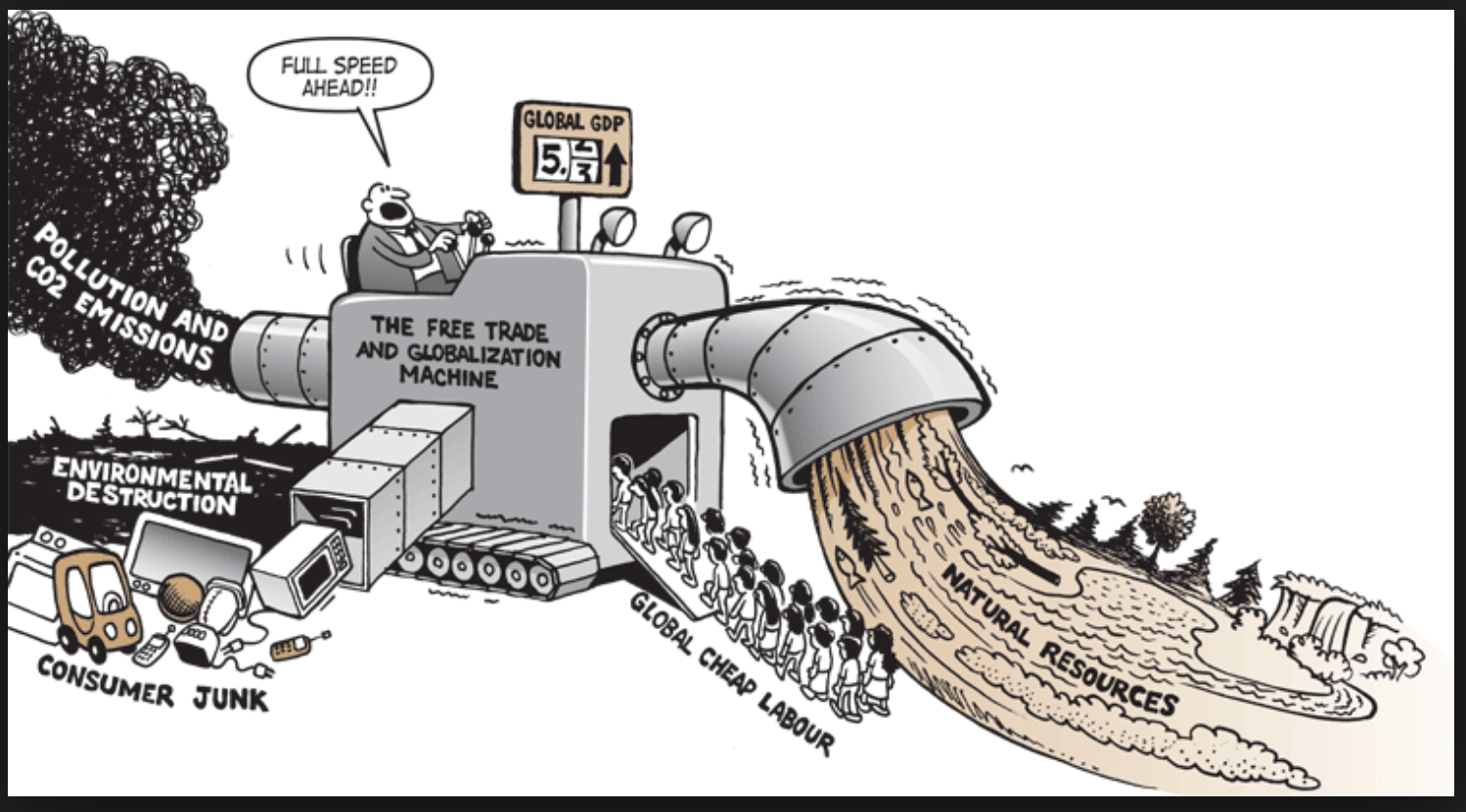

I want to make it clear that whatever else is in a progressive trade strategy, climate change is unavoidable as a central topic. Either because the global economy will be coping with the consequences, or because it has done dramatic stuff to meet the targets. The central business challenge is to save the planet. That may sound trite, but we are talking about enormous opportunities in business, investment, employment across the global economy. The problem at the national level is that the talk is all about the competitiveness impact on trade exposed sectors, especially agriculture. So government is simply neutered by exemptions to biggest polluters of heavy industry and agriculture. That can be amazingly persuasive to people who have not thought about trade theory.

I want to talk about how to handle that in a progressive setting. Getting a global price on carbon, or even at a national level, is central to getting structural shifts in the economy. It is unlikely that we will get a globally harmonised carbon price in the foreseeable future, so we have to be looking at nationally set carbon prices, and we have to look at the consequences of high carbon prices for the trading sectors in this economy, that is our export sectors and to some extent our import-competing sectors.

Because there won’t be global harmonisation there has always been a strong case for border adjustments. To understand that you have to look at the way we apply GST in NZ – we mark up prices of goods and services bought here to provide revenue for the government. With a carbon tax you mark up the prices of things that are being traded in the NZ economy to capture the externality of carbon emissions. So the goal is a little different but the instrument is the same, it’s a tax. What do we do with GST? If NZ exporters had to export with 15% added on to the price they would be considerably less competitive. At the border as things leave, the tax comes off and they go out at the pre-GST price. Stuff coming in arrives without the GST added and is competing with local products so they put GST on after it crosses the border. This is not rocket science.

But we are talking about the space for democratic national action, which was also talked about earlier today. What kind of space is needed for states to address the climate change challenge? If they are going to use carbon taxes, how do we need to protect their ability to do that? I want to emphasise that if we have border adjustments in place for carbon tax, all this stuff about trade exposure is gone – you don’t have to exempt anybody or run around having lobbyists telling you about how the Tiwai point smelter will close, etc. You trade in the real world outside our borders on the prices that prevail out there. This is fully consistent with the principle of free trade. It keeps the playing field level, while enabling individual economies or groups of economies to use carbon taxes to pursue zero carbon economies.

There are 2 other points: 1. Bill Nordhaus has been proposing carbon clubs of nations who get carbon taxes harmonised and form a trade area with a single tariff to protect them from dumping from high carbon economies. That principle of dumping has always been there in trade literature. It’s always been the case that dumping is a breach of the spirit of free trade. We are talking about countries that sell untaxed high carbon goods into an economy where low carbon strategies are being pursued, in which case you put an anti-dumping duty on when they come over the border. At same time, exporters from low carbon countries that are fully competitive, aside from the carbon tax they pay on them, have to be able to sell their goods free of the carbon tax in overseas jurisdictions that have high carbon policies.

A carbon club can start with one country: a lead country does it and invites others to sign on. Ideally others will. Maybe no one does. But there is no downside. For example, Tuvalu could be the first mover. When there is a critical mass, the club has its own dynamic and grows. There is nothing to lose. Incentives to join will become stronger as climate change pressure comes on and the damage from not joining becomes bigger over time.

This is not an ideal world. You can see this is second best response to the inability of the global economy to get a harmonised global price in place. The moment it does that you can let the border adjustments off. It’s a pity that there’s positives and negatives of Trump. He is weaponising tariffs as geopolitical manoeuvring in an offensive against China. It does mean, though, that the strategic use of tariffs and subsidies to pursue strategic objectives is now back on the trade agenda and progressives don’t need to be fearful of that. Once you have those options being played around with you can harness them to progressive objectives.

More broadly, Russel Norman talks about global citizenship and opens up the challenge that local identity and a place to stand is where a lot of progressive politics will come from. I want to stand back and sketch some big picture stuff to identify the 2 strands that have to go into progressive trade policy. One is the Maori, tangata whenua stance and the Treaty, and the other is the progressive tradition in the white settler society. If you think back to the 1940s when Labour was in power and Peter Fraser was Prime Minister and NZ went off to the UN founding meetings and so on. Social democrats in NZ had an internationalist vision of constructing a better world order, coming from a strong place to stand under the First Labour government.

If you look back, we had a global economy that was dominated by the old empires and Rod Oram talked this morning about asymmetric power. But power is asymmetric. That’s what power is. If you get symmetry, power loses its bite. Power against countervailing power gives you balance. In a sense that’s what happened in the 1940s – the great powers ruled the world and sent their navies around to enforce their will. That was broken. Decolonisation took large chunks of the world out from the control of the great powers. We moved into an internationalist vision of a global economy in which people could realise their own identities within their own spaces.

Then in the following half century we have a new imperialism. It’s the imperialism of transnational capital operating with, instead of navies, ISDS and international trade agreements, and so on. And the opportunity for progressive movements is in wanting to get countervailing power back into the system. That means trade agreements which respect national democratic spaces for protecting values that matter to people, while seizing the opportunity to exercise global citizenship on something that is collectively important to us like climate change. We need new international architecture that will take us there. It’s a new conjuncture, but social democrats ought to be standing there simultaneously holding their national spaces, because like it or not the nation is the repository of countervailing power in the world system still, while stepping out to create something new collectively. That’s my little manifesto.

Question from the floor: If we have a border tax adjustment for exporters, how do we keep the pressure on them to cut their emissions if they are exporting to countries that have high emissions?

Geoff: This is second best policy, how a nation can operate within its own borders. Second best, where others aren’t being global good citizens. A ring fence enables an efficient national policy without it being overwhelmed form outside.