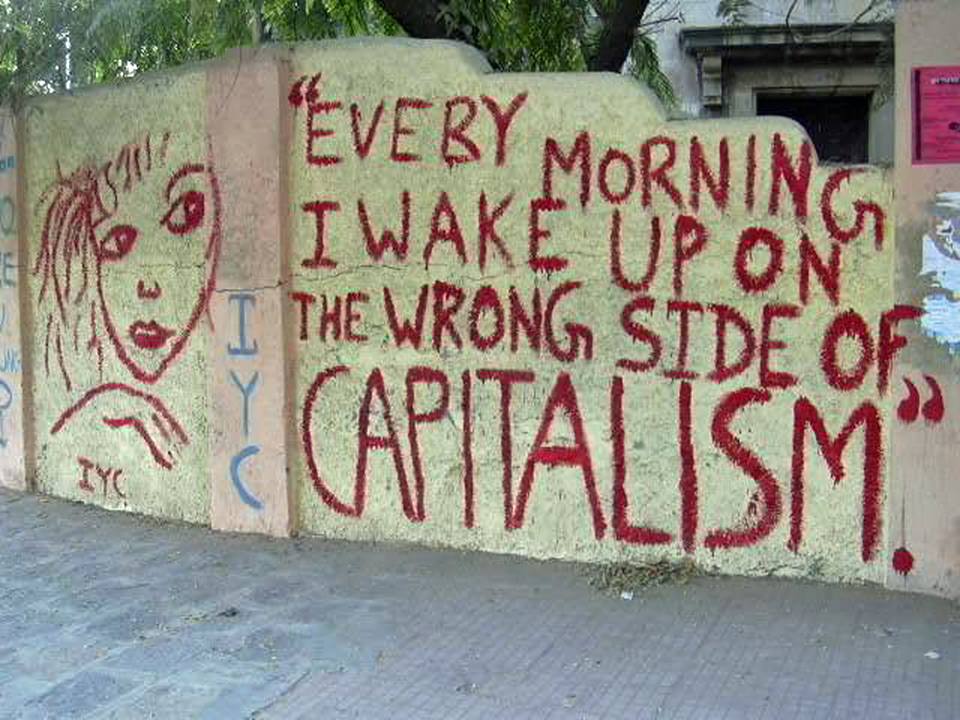

While we don’t use the c-word ‘capitalism’ much these days, Winston Peters created a bit of a stir by mentioning it in his coalition announcement speech. And former Green MP Catherine Delahunty, on Backbenchers (television), said that we must address it. These days we sometimes prefer the putative synonym ‘globalisation’ when we want to make an ideological point about the capitalism that many ‘progressives’ see as driving us to economic, social and ecological ruin.

While part of the reason we relegate ‘capitalism’ to the shadows is a lack of literacy in and interest in political economy, the bigger issue relates to the absence of history in far too much of our thinking. Indeed, the word ‘globalisation’ is commonly used to talk about ‘now’, with a sense of history going back no further than the 1980s.

Capitalism is one of the biggest – it not the biggest – ism of human history. It’s a reality, not a policy. Nobody in the year 1300 said, “lets revolt against feudalism and replace it with capitalism”. Capitalism was an outcome made possible only by a Malthusian event – the Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century – so large that the fundamental relationships between classes of people (in Europe especially) were splintered. Enough social and economic space was created for a new ism to quickly evolve in place of feudalism.

Karl Marx’s nineteenth century analysis was about capitalism, its evolutionary success, and its internal contradictions. His analysis was largely a development of the classical economics (c.1810s) of David Ricardo (in the history of economics, Marx is widely understood as a post-Ricardian) and James Mill (father of John Stuart Mill). Classical economics is itself a development of the classical liberalism of John Locke (c.1690s) and the economic liberalism of Adam Smith (c.1770s). While Marx did mention a benign post-capitalist order – he called it ‘communism’ – he understood that it could only arise from the collapse (indeed, realistically, the Malthusian collapse) of capitalism. And he presumably understood that benign communism was only one of a number of possible unknown isms that might arise beyond the collapse of capitalism.

(We might note that not only are we just a few months away the bicentenary of Marx’s birth; this year is the bicentenary of the publication of the most historically significant – though not the most popular – economic tract ever published, Ricardo’s ‘On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation’.)

There are alternative non-Marxian ways of critiquing capitalism, or what we think of as capitalism.

What we have today, and have had in various iterations since at least the time of John Locke, is semi‑capitalism or skewed capitalism, a stunted version of capitalism succoured by the ignorant rich because it skews the income distribution in their favour.

What political progressives need to be doing is opposing semi-capitalism, in favour of a fully-rounded capitalism: productive, efficient, equitable and environmentally sustainable (the four goals). For capitalism itself to be sustainable, it needs a mechanism to stabilise income distribution (probably at a ‘Gini coefficient’ for income of around 0.30 [30%], much like New Zealand’s income distribution in the 1970s). We need a capitalism with a thermostat set at ‘Gini-30’.

Modern semi-capitalism includes a market mechanism of resource allocation and an underused ‘Pigovian’ method of using taxes and subsidies to address merit and demerit goods, and externalities. In its most benign form, it is based on private property rights, consumer sovereignty, and enlightened self-interest. In semi-capitalism, governments are important, and they are there to enforce property rights. The Pigovian welfare principle extends to third-party property rights – tantamount to public property rights – while also nudging consumers into more informed expressions of consumer sovereignty.

In addition to the familiar global market mechanism – which could maintain economic efficiency (one of the four goals) if we lived in a Gini-30 world – we need a capitalism that builds into its core the important but very distinct concepts of public debt and public equity.

Private businesses and households – taken collectively and globally – always spend less than they earn. They always have and they always will, notwithstanding the converse of this in post-1980s’ New Zealand history. This universal practice of precautionary saving is better understood as an insurance premium than as a nest-egg to be spent at an end-of-life party. By definition (given that, in the private-public dichotomy, there are only two sectors) the only way this private‑surplus habit can be accommodated is through public sector financial deficits. And public financial deficits accumulate as public debt. Public debt is utterly central to functioning capitalism, because public financial deficits offset private financial surpluses. If both private and public sectors are genuinely trying to run financial surpluses at the same time, the only logical conclusion is the complete collapse of capitalism. It’s a mass‑casualty financial race to the bottom.

It is modern Japan that has pioneered the use of public debt as a stabilising force that broadens semi‑capitalism. The Japanese public prefer to lend to their government – at zero interest rates (with the shared understanding that individuals will only withdraw these savings in the same context as if making an insurance claim) – than to pay increased taxes.

New Zealand is not a country that should be seeking to enlarge its public debt at present. Mounting private debt is keeping this local branch of the semi-capitalist global economy ticking over, and is generating the tax revenue that gives the New Zealand government its present surpluses. While there may be an efficiency issue in New Zealand – the consumption and investment legacies of private deficit spending in New Zealand may be less valuable than the alternative legacies of public deficit spending – there is no stabilisation case at present for the New Zealand government to compete with the New Zealand private sector for loanable funds.

Public equity is the crucial component of the Gini-30 thermostat. We can think of the economic pie as being divided into two substantial portions (‘halves’, but not exact halves). One half represents the fruits of private equity – labour and private capital. The other half represents public equity.

We are slowly – and very stutteringly – developing ideas of private equity. I saw this article in the New Zealand Herald on 14 December (Robertson walking tightrope between paying for policy and controlling debt) in which four [sic] or five capitals are being promoted by the New Zealand Treasury (no less) in “world-leading” research as the basis for future prosperity. These capitals are not news to me.

Twenty years ago I published A New Fiscal Contract? Constructing a Universal Basic Income and a

Social Wage (Social Policy Journal of New Zealand). Last week I published, for the AUT Policy Observatory, the report Public Equity and Tax-Benefit Reform in which I explicitly referred to the ‘Six Capitals’ of Jane Gleeson-White’s 2014 book Six Capitals, or Can Accountants Save the Planet?. Of these six capitals, three – natural, intellectual, socio-cultural – are inherently public. The remaining three capitals – human, manufactured, financial – each have substantial public domain components (education, physical infrastructure, monetary/banking system including central banks such as New Zealand’s Reserve Bank).

This preponderance of public capital means that one ‘half’ of the economic pie – alternatively understood as ‘output’ (GDP) or ‘income’ – is inherently public income. Our main task is to account for this public half as if it was available for public distribution. However, we should not be trying to measure the unmeasurable.

(On the matter of measurement-mania, there are two cynical ways to reduce a country’s poverty metrics: 1. Give people trapped just below the poverty-line a few dollars more so that they are trapped just above the poverty line; 2. Reduce the median income [ie increase inequality] so that more poor people come within 60 percent of that median.)

What capitalism needs is a public income pool that complements the private income portion. If the Gini coefficient is above 0.30, then the public income pool is too small (meaning the private ‘half’ of GDP is relatively too large). This would mean that the government is levying too little as income tax, and distributing too little income from the public pool. The appropriate remedy of democratic capitalism would be for the people’s representatives to levy more, and to distribute more. Conversely, if the Gini coefficient is below 0.30, then the public pool is too large; the income tax rate should be cut and public equity dividends reduced in favour of higher private after-tax incomes.

We can see here that public equity acts as a systemic thermostat to regulate income distribution at around the desired Gini setting. This is the requirement that can make capitalism sustainable. In doing so, it can allow individuals to manage their hours of labour (ie hours committed to the marketplace). Individuals, by choosing to work fewer hours would reduce the private components of their incomes. If large numbers of people choose to work fewer hours – and this is not matched by other people choosing to work more hours – then the economic pie would shrink (possibly, but not necessarily, a bad thing) and the public income pool would reduce markedly. This would in turn cause more people to revise upwards their commitments to the labour market.

Full democratic capitalism extends our present Pigovian semi-capitalism through its acceptance of both public debt and public equity as means to remove semi‑capitalism’s ultimately fatal skew. Do we try to bring forward a Malthusian resolution that will lead to some other ism replacing semi‑capitalism? Or should political progressives seek to build a full-bodied sustainable capitalism that recognises the relationship between capitalism’s private and public domains?

And that ladies and gentlemen is the history of money every one should know.

I see a few problems with Keith’s analysis.It does not take account of the fact that there are finite resources in the world.Whether you like it or not, our economic system has to intelligently share these resources among the population to be ultimately sustainable.Capitalism does not do that, nor has it ever.By and large, there is no advanced capitalist economies in the world in which inequality is not growing. So a method must be created to solve this or society will eventually explode into revolution.Let us examine a school as an example of an economic entity. In N.Z. at the moment, and there are exceptions to this, the salary differential from those entering the teaching profession to those becoming Principal are at the order of 3 to 6 times the rate. Imagine a change to a salary differential of twenty to one, or fifty to one, as we see happening with our Corporations and Public Service , but utilising the same amount of resources. What do you think would happen in our schooling system? Our economy is like a highway with rules constructed for the super rich and no speed limit. The answer is obvious.For the greater good and indeed for the survival of society, rules need to be implemented so income levels are controlled within intelligent sustainable parameters.And so also for the accumulation of wealth. No amount of fiddling will alter this basic immuteable prescription !

Good analysis of the reality of Capitalism Pete.

Capitalism is only workablel if some are taken advantage of by others and this is fact.

Imagine if the whole population went for the same bussiness oeration and sold all others their product at the same price.

First you would have over supply, and no cost cutting if they carteled the price as petrol outlets do so no competition would frourish and an over supply and stagnation would evolve into lower prifits and then some would go bust.

We all cant live this way so a better way would be to produce enough and distribute those commodities amongst the countries people firstly and sell the eccess to overseas buyers.

Workers would run all companies like Co-operatives again as we did post depression as we gain global recognition in the 1950’s as one of the best countries to live then…..

“Private businesses and households – taken collectively and globally – always spend less than they earn. They always have and they always will, notwithstanding the converse of this in post-1980s’ New Zealand history. ”

Surely this is an aspiration rather than a common achievement historically. I would suggest that the period from WW2 to the 80’s when households were able to spend less than they earned was the historic abnormality. Not ” the converse of this in post-1980s’ New Zealand history”. Now of corse households are on average spending more than they earn as household debt multiplies.

” By definition (given that, in the private-public dichotomy, there are only two sectors) the only way this private‑surplus habit can be accommodated is through public sector financial deficits.” Again surely this is not an absolute inevitability but simply an inevitable consequence of money supply being almost all made out of bank issued debt. There is no physical reason why private surpluses have to be at the cost of public deficits, it’s an entirely self imposed construct of society.

If we are going to experience a collapse next year as you have predicted it is because of this stupid nature of the monetary system we all put up with. It is resources, human, natural and constructed that are the legitimate limits to our wealth private and public, money to facilitate their interactions is an arbitrary invention , and pretending/ accepting that it’s supply is a limitation at least to public sector is wrong. Both morally and practically.

D J S

You can calculate actual private financial balances for any country as the current account balance minus the government balance. In NZ at present the current account balance is negative (deficit) and the government balance is positive (surplus). So the NZ private balance is strongly negative.

For the world as a whole, the current account balance is always zero, so the private balance is simply minus the government balance. Globally, government balances are deficit balances, and I know of no time in history when they were not.

In the world economy, by definition, all financial balances add to zero. So if the world is divided into two sectors, the financial balance of one sector must be minus the financial balance of the other.

My claim is that the private sector is usually the active party, so therefore the global government balance will always be determined in large part by the financial predispositions of the private sector. If governments try to run financial surpluses when the private sector is also trying to run surpluses, then both sectors will be thwarted and the global economy will tank.

“For the world as a whole, the current account balance is always zero, so the private balance is simply minus the government balance. Globally, government balances are deficit balances, and I know of no time in history when they were not.”

Obviously but this ignores the reality of how those balances are distributed and controlled. Unfortunately we do not have a single world currency and we try to even things up through exchange pegs or floating currency rates….these have not prevented distortions between economies…your example of Japan evidences that.

NZ can be said to have been living beyond its means for several decades and at some point will find itself having to default despite a floating exchange rate….that dosnt change the worlds balance sheet but its impact on the inhabitants will be significant….i.e. Greece.

So if we are to avoid such a fate then not only must the GINI be controlled but also the use of FX to enable a foreign trade balance ….and thats where the political problems begin.

You can calculate actual private financial balances for any country as the current account balance minus the government balance. In NZ at present the current account balance is negative (deficit) and the government balance is positive (surplus). So the NZ private balance is strongly negative.

For the world as a whole, the current account balance is always zero, so the private balance is simply minus the government balance. Globally, government balances are deficit balances, and I know of no time in history when they were not.

In the world economy, by definition, all financial balances add to zero. So if the world is divided into two sectors, the financial balance of one sector must be minus the financial balance of the other.

My claim is that the private sector is usually the active party, so therefore the global government balance will always be determined in large part by the financial predispositions of the private sector. If governments try to run financial surpluses when the private sector is also trying to run surpluses, then both sectors will be thwarted and the global economy will tank.

How do you establish that the world current account balance is zero?

That seems to imply that total debt = total savings or surpluses. How do you establish that or do you just assume it? i strongly suspect that world total debt exceeds total savings by a wide margin.

D J S

Financial balances, and the balance of payments, are zero-sum games; by definition, not by assumption.

A country’s current account balance is its current receipts from the rest of the world (exports, interest, transfers) less its current payments to the rest of the world (imports, interest, transfers).

For the world as a whole, there is no ‘rest of the world’, so the Earth current account balance is always zero.

However, if someone establishes a colony on Mars, for many years that colony would run a current account deficit, meaning that Earth would then run a current account surplus. The zero-sum constraint would then apply to the solar system, not the world.

In Star Wars, the zero-sum constraint applies to the whole galaxy!

Thanks for your reply Keith

It’s clear enough that the international situation is a zero sum game, but what about internally which was the focus of most of your article? So net in each country rather than between countries.How do you establish that all debt both public and private is balanced by all savings,surpluses , or reserves?

D J S

Deficits are not the same thing as debt (but they contribute to debt). And the main focus of my article was global, not NZ domestic. However ‘policies’ are domestic, given that governments are domestic.

Strictly speaking, in proper accounting, all liabilities (eg debts) must be matched by assets of equal value. So when a liability is discharged, an asset disappears also. And when an asset is realised, a liability is discharged.

Every item of debt is owed by one party (as a liability) and owned by another party (as an asset).

All of the public debt in the world is represented in the global balance sheet as private sector assets (wealth). If you own a government bond, that’s a part of your wealth.

Thanks again.

Sorry to keep on but others may get something out of this too ,notwithstanding Historian Pete’s fair comment below.

So when in the article you refer to Public deficit cf private deficit (current account not overall balance) , Rather than thinking government account re the banks cf private account re the banks, you are including the banks as part of the private sector. Am I getting this right? And “assets are financial assets i.e. loans rather than real estate or plant which might be thought of as collateral ?

Cheers D J S

Banks of course are private businesses. But they are special kinds of business – intermediaries – which hold both government and private debt as assets on their balance sheets.

Pure financial assets are loans and derivatives and the like. Other assets – including real estate – are equity. But equity assets have many of the same characteristics as debt assets. If a person sells their house for a million dollars, and spends all the proceeds on new goods and services, then that’s goods and services that could otherwise have been enjoyed by workers spending their wages. So the ownership of that house, when liquidated, represented a liability met by the working class.

For policy of the sort you propose, income equity, the owners of capital would have to allow the state to expropriate part of that they regard as their private wealth for the purpose of redistribution to those who lack wealth.

The fate of Keynesian reforms proves otherwise.

The attempt to tax profits to fund state spending to boost consumption and entice capitalists to invest in production does not work unless profits are guaranteed. The GFC proved that printing money to induce capitalists to invest in production presupposes profitability. Failing that, capitalists use new money for speculation or personal consumption.

When we ask what is needed to restore profits, it becomes clear that that includes not a policy of income equality, but further radical cuts in workers share of value, social wage, basic rights, and the destruction of the structuring (more cuts) of the value of fixed capital (plant closures, M&As etc) by the most powerful monopolies.

Therefore, there can be no income equity under capitalism because the long term dynamic of capital (especially the form of capital under which we live, state monopoly capitalism) is towards greater and greater destruction of value (wealth) and of the sinking of the working population who become redundant in production into ‘misery’.

Karl Marx called this the “General Law of Capitalist Accumulation” Chapter XXI Capital Vol 1. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch25.htm

As for capitalism ending in some “Malthusian resolution” Marx has this to say:

And now for the good news!Last Thursday, a group of leading inequality researchers, includingThomas Piketty,Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, published its 2018 World Inequality Report,which shows that the United States is far more unequal than the advanced economies of Western Europe, as well as the rest of the world.

The researchers reported that the income share of the top 1 per cent of U.S. income earners rose from 10 percent in 1980 to 20 per cent in 2016, while the income share of the bottom 50 percent fell from 20 percent to 13 percent over the same period.The bottom 90 percent controls 27 percent of the wealth today, compared to 40 percent three decades ago. Add to this the effect of Trumps tax cuts for the rich.This amounts to the death of social mobility in the U.S., which in past epochs always leads to social chaos.

Add to this the extinction of Democracy, with two Oligarch run Political Parties plus an out of control Deep state,controlling the Congress, an economy run substantially by an unfettered corrupt financial system with non existent regulatory controls, a Fed chaired by a cocktail waitress, an out of control Military/ Industrial complex, Generals proliferating in the halls of Government, and corruption ruling the day in just about every Industry in the country. The pharmaceutical /Food/ medical industries are poisoning the populace.Couple this with a deranged President- Herr Trump,and out of control militarism.And unfortunately, given the impact of the U.S. economy and military presence ,we are captive passengers on this juggernaut as we head for the inevitable collapse of the U.S. Empire!

In this context, public equity versus private equity is perhaps a rather minor consideration!!!

As I love irony I can’t help but comment on the “Invisible hand of the market place” as coined by Adam Smith in the 1700’s. The general idea is that individuals persuing their own self interest under capitalism will end up doing what is best for society” as if guided by an invisible hand.” But the Gods are attracted to hubris, and in the U.S. with the military industrial complex, the invisible hand has instead picked the pocket of the U.S. people,producing shoddy aircraft like the F-135.The U.S spends ten times the amount of the next country, but has ended up with vaste quantities of sub standard equipment. The NSA has ended up totally dependent on Russia for space travel as the Russian rockets are better and less expensive than the U.S. ones. Somewhere in the Celestial Economic Cosmos, Karl Marx and Adam Smith are no doubt having a Christmas drink and snorting with amusement at the latest folly of the Exceptional People of the Greatest Western Civilization !!!

H P

The perfect example of the workings of the invisible hand are right now demonstrating themselves with bit coin. A completely valueless figment providing no possible benefit to mankind whatsoever is attracting most of the loose investment funds in the world . So much for the invisible hand.

Keith

I’ll start here again to give more space.

In this passage “By definition (given that, in the private-public dichotomy, there are only two sectors) the only way this private‑surplus habit can be accommodated is through public sector financial deficits. And public financial deficits accumulate as public debt. Public debt is utterly central to functioning capitalism, because public financial deficits offset private financial surpluses.”

There doesn’t seem to be a banking sector as separate from either public or private.

In this…” there is no stabilisation case at present for the New Zealand government to compete with the New Zealand private sector for loanable funds.”

There does seem to be a separation , as ‘loanable funds’ to either basically means the banking sector , and by my assumption a third entity in the narrative. Just as you describe it in your last, a special private intermediary.

So in the sense of the first passage Iv’e taken above, are you including banks within the private sector or not?

Banks’ profits, if unspent, contribute to private sector surpluses.

Otherwise banks are pure intermediaries, with both public and private customers. Best to think of them as pure intermediaries, which makes them irrelevant in the public-private dichotomy.

Of course banks actively participate in the process. All debts that they create through their lending are balanced by equal and opposite credits. If they lend to governments, those loans add to public deficits while at the same time adding to private surpluses.

Does that help?

A bit thanks.

It clarifies by implication that you article includes the banks as part of the private sector,but though you might think it’s best for me to think of them as pure intermediaries I am not able to oblige as I know very well as you do that they are ultimately the source of nearly all if not all loan monies to private and public, and that these bank loans circulate to become nearly all if not all the credits as well. So they are overwhelmingly the creators and the directors funds to both. far from being passive intermediaries.

But thanks very much for the interaction . I’ll leave you in peace now .and Happy Christmas

David J S

Comments are closed.