When we discuss poverty, the two extremes seem to fall in two categories: beneficiaries and the uber rich. The “middle class” seems to be an amorphous blob which fills the gap between the two, and (according to the law of post-90s politics) is the demographic which politicians have to appeal for votes.

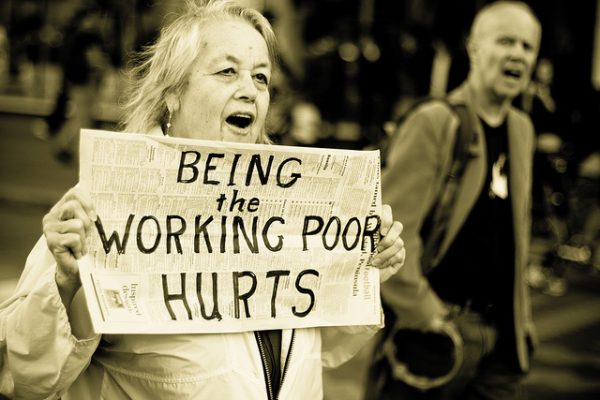

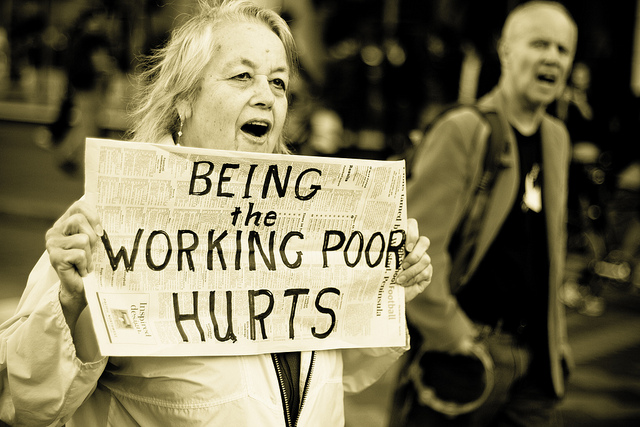

There is no denying the existence of the class structure. It’s not as clear as the Marxist interpretation of it was, considering the prominent use of credit cards, private debt, mass consumption, asset-rich and cash poor typecasts. But the foundation is still there, if not a little more convoluted. In fact, a relatively new academic term is now the “precariat,” which describes workers who have employment but are still struggling to climb the class ladder and never likely to.

It’s arguable that class division is even more unequal today, but with that top rung being a glimmering dream we now think is achievable through hard work, and so we marginalize the reality of a system that sets us back.

What I mean by the precariat are people who work full time as fall below the poverty line in New Zealand. And while we don’t have an official ‘poverty line’ in NZ (why not?) there are indicators the government use, such as the median household income. Even according to this, in 2013, 39% of households in poverty were had at least one or more people in full-time work. It’s worse now by some estimates.

Other international organisations condemn our child poverty rates – nearly 20% of children live their entire childhood in poverty. In New Zealand. With working families. The land of milk and honey, where suddenly we’ve run out of both and butter is at an extortionate price even though it’s made right next to us (hint: it’s because dairy is around 35% of our exports and worth fourteen billion dollars – why wouldn’t you cash in on that?).

The biggest problems facing the precariat (and frankly everyone) is how we don’t tax wealth, enable a corporate culture divorced form responsibility, and distribute benefits.

The simplest solution is a “Tobin Tax.” It’s the idea that labour does not produce, manufacturer or even make things, and so we need to stop taxing labour and start taxing capital itself. Why should we tax a minimum wage worker behind the checkout at Countdown who is about to lose his or her job due to automation in a few years anyway, and tax those who have large investments floating around gaining more money while there is actually nothing tangible gained or contributed from it. Wealth begets wealth, while the minimum wage worker has P.A.Y.E and secondary tax on their other job they need to keep afloat.

It’s one of the problems with housing; 70% of New Zealand’s wealth is tied up in housing, while home ownership rates are plummeting to record lows. It’s a great place for those with money to invest. New Zealand was recently considered a tax haven due to our lack of disclosure laws. Google, Apple and Uber don’t even pay tax here because of our lack of enforcement on capital gains, and sneaky business practices like profit shifting.

Ideally, this new government will at least make waves in the property market, with crack downs on negative gearing and speculation.

And so when we discuss class division in New Zealand today, and the growing gap, it’s not as clear as simply the workers and the owners of production. You don’t need to own production to generate wealth anymore, and management can’t be considered class traitors. The middle class is being left behind.

When we rely on business to create ans sustain jobs, there is the assumption they have a responsibility to us also, through an unspoken social contract. However, increasingly precarious work and a lack of corporate responsibility to provide decent, sustainable work exacerbates a class division. “The grind” isn’t a term used to describe intense physical work anymore, it’s now interchangeable with persistently low wages and a seemingly endless road ahead to feel like you’ve stepped up in life. This is made worse by globalization and the abuse of outsourcing that comes with it. We can’t help that our boss, or competition, uses cheap labour to produce cheap goods to cheapen the competition. What we can do is utilize the labour itself – and a union in London is doing just that, by allowing “joint employer” conditions in collective agreements. This idea is going through the courts now in tribunals in London. Workers who are out-sourced (and to a lesser extent contractors) are often paid less than employees, have less rights (like annual leave and kiwisaver contributions) and the company actually profiting form them doesn’t need to take responsibility at all. Often they get tossed around in a bureaucratic game of whack-a-mole when something goes wrong, and take no account of their work conditions.

Creating good employment means laying ground rules. You get ‘x’ hours, and you get paid ‘x’ amount. You get a decent contract with leave and entitlements. I understand the need for flexibility, but government bending over backwards for flexibility has slowly eroded workers value. Combined with automation and outsourcing, it’s left workers fighting over crumbs.

In a changing workforce, we need to adapt to modern class struggles. This means picking the battles, and being productive in how we change them. Railing against the concept of globalization or the free market will not help, because it has become almost a part of existence to acknowledge these things. What needs to be done is to curb the gross excess that it produces, and provide equity. Bouncing from extremes will not do that, but basing polices and legislation on fairness and practicality will.

For example, benefits. What irks me is the lack of incentives to transition to work. I’ve written about this before, and I still see it. Why would anybody wanting to find work and ween themselves off the benefit want to do that, for only a few extra dollars than if they didn’t work at all? Students and mothers alike face this problem. I discovered a person the other day who declined a pay increase to the living wage, because her entitlements (such as a accommodation supplement) would have been reduced to the point where her budgeting advisers said she would have actually lost money. Working for families is a bureaucratic nightmare also.

There is no doubt out welfare system needs reform, and a massive one at that. The epitome of the precariat is someone who works hard, improves their lives very incrementally, and is still reliant on the state to supplement a corporate for low wages. That’s what many government benefits are – subsidies for private individuals or companies who can deflate their expenditure. Surely we can do better. And there is little doubt a universal income would streamline much of this and create a more equal platform.

So if politicians are looking for votes, it’s becoming clear that the ‘middle class’ is becoming a misnomer. In a world of abundance, where 60% of the waste we throw away is edible and children are starving, we need to change the narrative. We need to talk about the growing class division; not about the means of production, but between the precariat and those who have excessive amounts of capital. The world is changing; and if we make it a better place we need to make changes that keep pace.

Damon Rusden is a chef, journalist and law graduate with an avid belief in civic education and accountability. He was also a Green Party candidate.

I am 73 and 11yrs ago I was feeling secure as I was entering retirement inside three years time, but since 2009 I have been living from hand to mouth, as the new older poor middle class.

Yes we have been forgotten by National and are hoping that the new Labour coalition will level the system for us all as to few rich folks are getting the biggest part of the pie now.

There is going to be civil war in No Zealand. A child can see it coming from a mile off…

more like an economic collapse i think

civil unrest by soon to be bankrupt home owners

Comments are closed.