So What is the Purpose of Schooling?

In a comment on my recent article The best Education Minister NZ ever had, Mark wrote the following:

“Any education system ultimately succeeds or fails on whether its students can read, write, do mathematics, and understand science. On these measures, NCEA is letting our students down—especially a significant proportion of both Māori and Pākehā.

Humanity landed on the moon, built skyscrapers, and created modern civilization under traditional, structured teaching methods. What evidence, Mr Allach, is there that the methods you propose can build a civilization greater than what the West has achieved, and the East is in the process of achieving and perhaps surpassing?

And yes, if something cannot be measured, it does not count. Otherwise, we could delude ourselves into believing we are doing fine when in reality, we are not.”

Mark made some good points here that are very relevant and need to be discussed, so here goes – note that my expertise and experience was in primary education, and so I will be writing from this background.

I’m not qualified to write authoritatively about secondary education. Just because a) I went to secondary school, b) my kids went to secondary school, and c) some of my grandkids are presently at secondary school, doesn’t make me an expert, so take that into account when reading the following.

First, it goes without saying that competency in Written (and Oral) Language, Reading, and Mathematics is essential. Defining what that level of competency should be is another matter, but at a guess I’d suggest the end of primary schooling (which includes Intermediate Schools) or the first year or so of secondary would be about right.

Why do I set this level? Because that is the level that most adults will use in their lives – when was the last time you used algebra to solve a problem, unless of course you are in a career where this is part of your work? When was the last time you wrote a long treatise about something, or even a long letter? Get the point?

Students who have the aptitude and interest to go further in academic subjects should have every opportunity but I question whether this should apply to all. NCEA was developed to address this, to provide non-academic minded students with opportunities to receive credits for their studies. Clearly NCEA needs to revisited after 25 years, but I’m adamant it should not be replaced by a winners/losers reversion to the past, as Maharey commented.

Consider your own post primary education and how relevant it is to your present life.

Mark also highlights the need for science understanding. I am in full agreement with him.

The tragedy of the primary school curriculum changes over the last 35 years, exacerbated by the last National led government’s focus on National Standards, and the present government’s narrowing of the curriculum, is that proper hands on science has almost disappeared from the classroom. There’s no time anymore, as teachers are obliged to spend the bulk of the day on the basics.

I say ‘hands on science’ because true science is a process of curiosity, investigation (experimentation and document research) and the drawing of conclusions. The didactic approach of ‘The Science of Learning’ ideology would reduce science to children having facts poured down their throats, which is pedagogical nonsense. The obvious thing, for a start, is that learning received passively (i.e., where children sit at desks and are fed ‘facts; and ‘knowledge’) tends to go in one ear and out the other. Again, here’s a little test for you – how much do you remember of the things you were expected to learn during your schooling? Do you remember swotting for an exam, only to find that whatever you’d learnt was gone a week or so after the exam?

There’s a wealth of research that shows understanding and memory retention is far higher where children are actively involved in their learning and where the topic makes sense to them and therefore interests them – this is the personalised learning that Maharey mentioned.

Picking up on Mark’s paragraph about humanity landing on the moon, etc. Yes it is true that modern science, mathematics, and technology has created our world and will create the future world, as well as solving problems we cause along the way. As Mark says, the East is going to take over the leadership here, without doubt – just look at China’s road and rail network for example.

I’d suggest, however, that the percentage of students who will go on to work at that level, regardless of country, is actually quite low. The opportunity needs to be there for all those with that level of interest and potential to achieve their goals, for the good of the society and the country (which immediately begs the question why we force them to take out huge student loans when it is the country who will benefit).

But what about the rest? Are they to be discarded into the ‘drop kicks’ and ‘bottom feeders’ pile just because their skills don’t fit a narrow academic focussed agenda?

And what place is there in the ‘The Science of Learning’ for the Arts? While science, mathematics and technology have given us the physical world we live in, the contribution of the Arts is equally vital. Where is the emphasis on that? Would you like to live in an “arts’ free world? Various future focussed dystopian books have explored this e.g., Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four.

And the big omission is the development of originality and creativity – these attributes are vital to children’s future lives – it is easy just to regurgitate learnings but being able to apply these in new and different ways is very important today and in the future. Many of the points Mark made about how science etc have developed today’s world have been developed from an original and creative thought and insight. Again ‘The Science of Learning’ and the ‘Knowledge Rich Curriculum’ does not facilitate this.

Maharey noted in his article that New Zealand students continue to score near the top of the scale for creativity, something which those people who maintain ‘New Zealand education is failing’ overlook.

Mark added a further comment:

‘“But only in the sense that what is relevant and of interest to a learner is used to motivate them to engage. In short, it is just good teaching.”

If we only do things that interest and motivate us, that is poor self-discipline.

The most important thing one can teach kids is not to do things they like or want to do, but to do things they do not want to do. That is self-discipline, to sacrifice now for reward in the future.

Motivation is crap as it is a transient unreliable ‘feeling’. Self-discipline is key. To keep going even when one feels crap.’

An ideal of the schooling system is that students leave it with the desire to keep learning and the skills to do this for themselves. I was going to say education system, but to be accurate schooling and education aren’t the same thing. Schooling is merely one way in which people can get an education, and this is nearly always overlooked. Children being forced to learn (if that is actually possible), whether they are interested or whether they like it, is an excellent way to ensure the desire to learn is extinguished, and sadly, it is my observation that this applies to the majority of our adult population.

Which brings me to my next point – for the first time in history virtually all human knowledge is available at our fingertips, through access to the internet. Anything the ‘knowledge rich curriculum’ can provide is but a very very minute fraction of what is available. Surely a modern schooling system should train students how to make best use of this, to teach them research skills so they can find what they need and, most important of all teach them critical thinking skills so they can appraise and evaluate what the internet delivers. Learning how to ask the right questions is a vital skill.

This is especially so now that ‘artificial intelligence’ (it’s not) otherwise known as large language models, are starting to dominate and through their integrated chatbots, delivering increasing amounts of dubious and unreliable answers to questions. Students must learn how to critique and evaluate these – a new version of literacy that is of vital importance.

So the aim of our schooling system should be to equip students with a sufficient level of competency to enable them to meaningfully participate in life, and that will enable them to continue their studies in the school system in which ever direction they choose. On top of that they should retain the desire to continue learning after they leave school, and have the necessary skills to do this.

… is to make lifelong social connections. So much time is wasted at school in “attainment” and not enough spent on “achievement”.

Good comment and I have no problems with most of what you write.. There’s a big difference between the science of learning and ‘The Science of Learning’ espoused by Stanford, Johnston and others. When I get time I intend to write about this referencing Dr Guy Claxon who explains the difference. The theory of Constructivism makes the case that all learning needs to connect with knowledge the learner already has – yet another reason why a prescriptive one sized fits all curriculum has problems. And I could go on … Thanks for the comment though.

Please do. I appreciate your thoughts. Commentary on education and learning is important … mostly we conflate the two and take it all for granted but a lot happening in this space, a lot not happening, and a lot that could be done much better.

Allan, I think you’re misrepresenting Johnston’s views. From what I’ve seen, he doesn’t present a narrow perspective at all. I was at a conference where he spoke earlier this year and was surprised by his balanced approach. I can only assume that much of the criticism aimed at him isbecause of his employer.

In contrast, Professor Guy Claxton seems to frequently stray from what the evidence suggests. His “learning powers” framework is not strongly grounded in the findings of cognitive science. Furthermore, his book, The Future of Teaching, resorts to strawman arguments and even personal attacks on what he calls the “DIKR cabal” to advance his agenda.

The issue is here is not ideologies, but between ideas supported by evidence and those that are not.

Mass education. Formal learning. Informal learning. All important, not quite the same. Historically, mass education emerged out of a specific context. I’ve seen a cartoon somewhere that cynically illustrates this purpose, kids being fed into a meat grinder and coming out the other end ‘knowledge rich’ and disciplined ready for their working lives – working for capitalism. I think all the kids in the cartoon were boys as the thinking of the time relegated girls to life of domestic servitude. But except for being more inclusive perhaps not much has really changed with mass education. It serves a socio-economic purpose.

But we shouldn’t knock mass education. Look at what it has given us in terms of life opportunity. It beats working in down the pit, lurching around on a whaling ship, or hammering in railway spikes. Life before mass education was pretty grim for many and surely its is a good thing.

Yet it’s not a level playing field – and never has been. That’s a story in itself.

But mass education – and all its components, the curriculum, pedagogy, testing and assessment – is not quite the same as ‘learning’ itself. For most mass education provides the basics – at least that’s the goal. Literacy. Numeracy. Hopefully some critical thinking. Yet learning happens everywhere, not necessarily only in mass / formal education. And it is lifelong. It can happen in apprenticeships, where young people are emersed in a community of practice and learn from doing with feedback from those who know more. This still happens.

But imv we are now obsessed with formal education and assessment. Measurement allows for accountability. Granted the world has changed. The old guilds have largely gone and arguably there are fewer opportunities to learn on the job. Entry qualifications are required, even if you’re cutting hair or working as an arborist. Yet, how many employers complain that newcomers with qualifications often know very little – learning on the job is still very much a thing.

Getting mass education right is important. But beyond the ‘basics’ surely ‘transfer’ of learning is the magical skill. And lifetime learning, the goal.

Your article questions the need for all students to learn subjects like algebra, suggesting that a basic level of competency is enough. However, a knowledge-rich curriculum isn’t about teaching obscure facts; it’s about building the foundation for higher-order thinking. Cognitive science shows that skills like critical thinking and creativity don’t exist in a vacuum. They are deeply tied to background knowledge. Daniel Willingham, a cognitive scientist, states that you can’t think critically about something you don’t know anything about. Limiting what we teach limits what students can do in the future.

You advocate for “hands-on science” and criticise the “didactic” approach. This reflects a common misunderstanding of what the science of learning recommends. It is not about passive instruction. Rather, it is about direct, explicit instruction that is grounded in how the human mind works. Research by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark has demonstrated that “discovery learning,” with minimal guidance, is less effective for new learners. The cognitive load placed on students trying to “discover” a solution often leaves them with little capacity for actual learning. A truly effective classroom blends careful teacher guidance with opportunities for deliberate practice and application.

You rightly point to the importance of creativity and the arts, but you mistakenly present them as being in opposition to a knowledge-rich curriculum. Creativity is the ability to combine and apply existing knowledge in new and innovative ways. You cannot be creative without a rich store of knowledge to draw from. A knowledge-rich curriculum provides students with the raw materials they need to be truly creative.

Your point about motivation is also key. While student interest is important, it is also transient. As Mark noted, self-discipline—the ability to do what is necessary even when it is not immediately engaging—is a vital skill. Developing this discipline by teaching students to persevere through difficult but important material is one of the most valuable things we can do for them. It equips them not only with knowledge but also with the resilience needed to be a lifelong learner.

Some good points. But “misunderstandings of what the ‘science of learning’ recommends”? I dont quite follow.

Isnt the science of learning infact a plurality of perpectives, a plurality of theories, a plurality of sciences. One could legitimately argue learning has little to do with depositing information in blank minds (one theoretical perspective underpinned by one particular science) but entails interaction and building on what one already knows (another theoretical perspective underpinned by a rather different science). Its just an example. When it comes to the science of learning there are a number of theoretical perspectives. Not one. A number of sciences. Not one.

On the ground teachers generally don’t think too much of ‘theory’ and I suspect expert teachers intuitively or purposely mix it up in the classroom. If they can. Although it is also said that many teachers simply teach as they were taught.

But formal schooling is a politicalised context and is prone to ideological capture, both left and right, progressive and conservative. The turf war over explicit teaching vs discovery learning is testament to this.

The right conservative grouping have commandeered the phrase ‘science of learning’ to fit their own narrow minded agenda, hence my differentiation, borrowed from Dr Guy Claxon, between the science of learning (although he later modifies this to the sciences of learnings) as opposed to the formal and very restricted ‘THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING’ used by Stanford’s favoured gurus. That implies there is only one science of learning, the only true way to enlightenment and salvation.

Bozo, thanks for your reply. I think we are closer to agreement than you think. You’re right that there isn’t one “science of learning,” but it is a field that has moved beyond pure theory to become an evidence-based discipline. It’s not about “depositing information in blank minds,” a caricature of instruction that the science would never endorse. Instead, it’s about using empirical evidence to understand how people actually learn.

This body of knowledge is what allows expert teachers to be “intuitive.” Their intuition isn’t a magical skill; it’s a deep knowledge of both their subject and effective pedagogical approaches. It is this knowledge that allows them to make informed decisions in the moment and adapt their teaching to the needs of their students.

Finally, you’re right to call out the “turf war.” The debate over explicit instruction is so much more than left vs. right or progressive vs traditional. It’s about what works best for all learners, especially those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds and do not have a rich store of background knowledge from home. A commitment to evidence-based practices is a commitment to equity.

I once – for an assignment – had a look at the reading ages of New Zealand newspapers. It averaged out at about 14 or 15 years. that was about 30 or 40 years ago It’s probably gone down a bit since then. I still think students should be able to read a newspaper, even though they are perhaps on the way out. Because they do actually produce news by sending people out to find stuff out, and they do check their facts on the whole.

And part of being educated as being aware about what’s going on about you in the world. Conservatives are trying to overturn this by ignoring the parts of history where – to say the least – White people didn’t do good.

Thank you for that lucid explanation Allan. I think that Mark has a simplistic view of things. “Motivation is crap as it is a transient unreliable ‘feeling’. Self-discipline is key. To keep going even when one feels crap.’”. Self-discipline is important, and yes, we sometimes have to do things that we don’t enjoy. However if we don’t enjoy an activity, we have to believe in its purpose. It is the job of the teacher to either get the student to enjoy learning, or failing that, to show the student that the learning has a purpose. That is not always easy, especially when the learning is of a general or abstract kind, like pure mathematics. Hats off to the teachers who succeed in that.

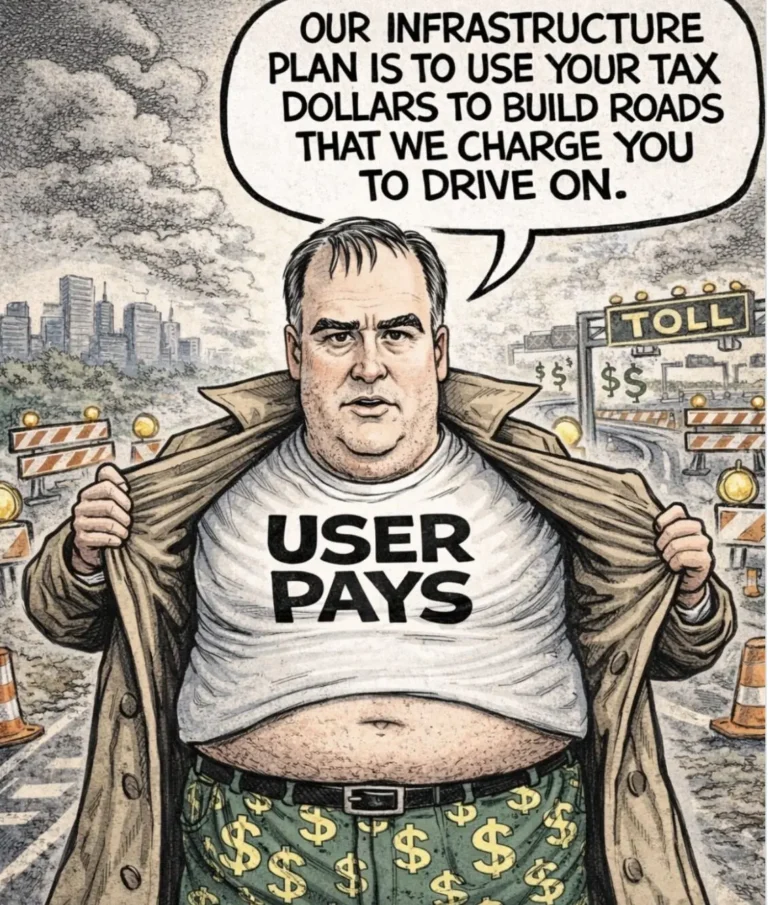

In my case I started out as a forestry worker, acquired qualifications, and ended up as a tutor in a forestry training school where we worked to NCEA unit standards. It was a system that served its purpose well enough. The necessary math and general science component was directly linked to tasks undertaken in forestry. That could be used to motivate the students. The “hands on” stuff was crucial. Getting students out in the field and teaching them proper techniques in practical situations. One of my big disappointments was when, after the neoliberal restructuring, the administration of the centre decided to move away from education in the field to classroom based education because “it was cheaper”. That forestry training centre which used to attract students from all over New Zealand and beyond, has now virtually collapsed. I am told it is down to a handful of students. That is how a false economy ends up.

In secondary schools you need chemistry and physics labs if you are going to teach science seriously. They are not cheap, but they are indispensable.

Many of the students we taught had struggled in or even failed School Certificate, but thrived on a vocationally oriented course, and valued the fact that they came out of it with a formal qualification that gave them esteem and a chance at a worthwhile career.

The main problem that I observed with the unit standard approach is that by seeing the field as comprising a number of separate tasks one risked losing the high level understanding that comes with a systematic education focused on broad principles and more abstract ideas. There is also a risk that in concentrating on specific ways of doing things one can blunt the capacity for inquiry and innovation. But all in all, the NCEA unit standards system served a purpose for individual students and for the industry.

“And what place is there in the ‘The Science of Learning’ for the Arts? While science, mathematics and technology have given us the physical world we live in, the contribution of the Arts is equally vital. Where is the emphasis on that? Would you like to live in an “arts’ free world? Various future focussed dystopian books have explored this e.g., Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four.”

Good grief. I work in the “arts”, and every day I use maths and science. They’re not seperate. Go spend some time on a film set and watch the “math and science and technology” at work.

Not to mention more obvious fields like architecture and design, unless we’re saying that the fibonacci sequence is no longer part of maths. Or that music theory is divorced from it.

Yes, by all means point out the generalization but I guess ‘working in the arts’ is a broad church. The technicians at Weta Workshop and the people in front of the cameras don’t do the same things. Likewise publishers and writers. Gallery directors and artists. Sound engineers and those on stage.

Thanks for the comment. Forgive me, I only wrote the article but I can’t see anywhere where I said there’s no place for maths and science in the arts. Can you please point me to that section? Someone needs to back in time and tell Escher not to bother using mathematics in his wonderful art work, or go even further tell Brunelleschi not to bother developing linear perspective or the great architects and castle builders of the past not to bother either.

You also said: “when was the last time you used algebra to solve a problem, unless of course you are in a career where this is part of your work?”. I’m in “the arts” and I use algebra (a lot). Many other people that I know in artistic fields use it as well. Plus of course non academic fields like many trades use basic algebra all the time.

You appeared to seperate science, mathematics and technology from the arts as if they were somehow different. They’re not. As if emphasising the importance of maths etc would give us an “arts free world”.

Forgive me, but I only read your article.

All I did was to point out that the current curriculum proposals don’t mention the arts at all. The recent senior secondary curriculum announcement removes art history from the list of subjects. Anything else you take from this is up to you

100% – at retirement age I’m looking seriously into enrolling in a BA and studying Philosophy and English Literature. Something I should have done at 17