GUEST BLOG: Ian Powell – How did our health system get into this poop

Last month (17 November) I gave an address to Kapiti U3A (Third Age) in Waikanae on the provocative subject of How did our health system get into this poop and how might it get out?

The first part of this subject, with some subsequent refinements, forms the basis of this blog post. The second part will be the basis of a subsequent post.

I began with a reference to the following quote attributed to a satirical senator of ancient Rome, Gaius Petronius Aribiter (who I have quoted occasionally in other posts and addresses):

We trained hard—but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we were reorganised. I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganising, and what a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while actually producing confusion, inefficiency, and demoralisation.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s adoption of a universal health system occurred as a result of the adoption of the first Labour government’s Social Security Act 1938.

For context it took another decade until the National Health Service in the United Kingdom was founded while Australia did not get its Medicare based universal coverage until 1984. The United States is still waiting!

Before universal coverage

Prior to colonisation the health system for Māori was based on hapu, their basic economic unit. It was largely self-sufficient coping with its own resources and supporting those in need, the elderly, sick and disabled.

As primarily British migration took off there were none of the support institutions (charity and the infamous ‘poor houses’ of their ‘home country’) to call upon.

Instead migrants had to make do. It was not until the early 1880s with the introduction of refrigeration that New Zealand was to become an export as well as domestic consumption economy.

In 1885 the Hospitals and Charitable Aids Act established a national system under the jurisdiction of specially constituted boards. This system continued with various refinements until 1938.

Universalism foundation

The Social Security Act 1938 introduced what became known as the ‘welfare state’ from the ‘cradle to the grave’.

In respect of health broadly it universalised and enhanced existing measures, introduced public hospitals and ensured that payments were not required for their care.

After a bitter battle with the medical profession (in those days led by the British Medical Association), a compromise was reached for primary care. This was not the medical profession’s finest hour!

Arnold Nordmeyer a key architect of Social Security Act

Under the compromise general practitioners were able to charge fees for service co-payments in return for receiving a government funded general medical services benefit (this continued although, in the 2000s, the benefit was changed to capitation based on patient enrolments with co-payments regulated).

The 1938 Act provided the foundation of the health system up to the adoption of the Pae Ora Act three years ago year. There was a structural separation between community-based and hospital-based healthcare. Public hospitals were run by statutory hospital boards.

Changing structures following changing culture shifts

This structure developed and continued until the 1980s with the arrival of 14 area health boards replacing the much more numerous hospital boards but also assuming responsibility for population health. These new health boards also had the potential over time to be involved in primary care.

They were gradually implemented over six years from 1983 beginning under a National government and completed under a Labour government. This was bipartisan decision-making.

Simon Upton was the health minister who introduced competitive market forces to drive the health system (unsuccessfully)

In 1993 the National government departed from bipartisanship by embarking on a new ideological direction. It introduced a new system based on competitive market forces as its prime driver.

This replaced cooperation which had underpinned public healthcare delivery since 1938. The structural divide between primary and hospital care was restored.

Public hospitals were run by crown health enterprises. These were state-owned companies covered by both the Commerce and Companies Acts. Consequently they were required to compete with both each other and the private sector.

Largely due to the fundamental contradictions of using a competitive market to provide a public good (with no ability to control demand) and increasing public unpopularity, this system was abandoned by the Labour-Alliance government elected in late 1999.

Annette King was the health minister who ended the competitive market experiment and established district health boards

On 1 January 2001 the Public Health and Disability Services Act came into force. Competition was out the door and cooperation returned. Twenty-two district health boards (DHBs) were established (subsequently reduced to 21).

To some extent DHBs were a return to the thinking behind the establishment of area health boards. Arguably they were similar to what area health boards may have evolved into had they been allowed to continue. But DHBs went further.

DHBs were characterised by being responsible for the whole of community and hospital based healthcare for geographically defined populations.

This included undertaking health needs analyses for their populations. It also marked a return to bipartisanship over the new structures.

The most common structural feature of a DHB was one or two 24/7 acute and non-acute base hospitals and the primary and other community care providers within its geographic boundary.

David Meates was the chief executive of the DHB (Canterbury) that progressed an engagement culture and integration between community and hospital care the most

This structural feature was directly relevant to a specific legislative function. DHBs were to focus on the integration of care between community and hospital.

Canterbury was the DHB that pioneered this focus the most and became a recognised world leader because of its success.

Culture and function before structure and form

All these structural changes followed an explicit cultural change. It is a mantra for those with this experience that culture change always trumps structural change for sustainable effectiveness.

Unfortunately it is too often not a mantra for governments, at least in respect of our health system.

Form (and structure) should follow function (and culture)

The universal health system created by the 1938 legislation involved a cultural shift away from charitable health.

It covered hospitals (secondary care), population health and primary care. Boards were established to run public hospitals while the health department assumed responsibility for the rest.

The structure of area health boards followed a culture change involving integrating more smaller and larger public hospitals, linking population health with treatment and diagnostic healthcare, and providing the potential for future integration of healthcare provided in communities and hospitals.

The replacement of area health boards with crown health enterprise operated public hospitals followed a cultural change involving introducing commercial competition as the health system driver.

This restructuring was consistent with the cultural change. The only problem was that the cultural change was nonsensical. Healthcare accessibility is a public good, not a tradeable commodity.

DHBs were the structures established to enable a return to cooperation rather than competition as the system driver, pick up from where area health boards left off, and to integrate healthcare between communities and hospitals.

Getting into the poop

Unfortunately putting cultural change before structural change was reversed by those responsible for the design and implementation of the Pae Ora Act (Healthy Futures) 2022 and the entities it created.

Getting into the poop

Our public health system was already in the poop before this latest restructuring. Much of the 2010s was characterised by relative underfunding (‘light austerity). But there was more to it than this.

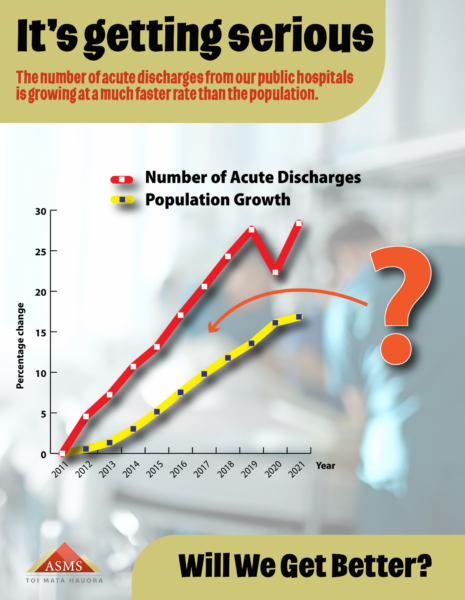

Since around 2014 the rate of acute hospital discharges has increased at a greater rate than population growth. This is a turning point for hospital occupancy by creating ‘bed-blocking’.

Consequences of acute hospital charges increasing at greater rate than population growth

Too many acutely ill patients have to stay in hospital beds longer thereby restricting access for non-acute patients requiring inpatient treatment. Longer wait times and overcrowded emergency departments are the most visible consequences.

This situation is not just due to population growth and aging. Impoverishment is increasing and becoming entrenched. More sick people are now sicker people.

It is also compounded by severe health professional workforce shortages beginning with hospital specialists in the late 2000s but, by the mid to late 2010s, extending across all occupational groups including nurses.

Fatigue and burnout are the unsurprising consequences. Perhaps also unsurprising has been the indifference to these consequences by successive health ministers.

Principle of Subsidiarity

But there is a further factor. The restructuring introduced by former health minister Andrew Little had more in common with the insight of Gaius Petronius Aribiter.

There has been a largely unacknowledged principle which had underpinned our universal health system since 1938.

Principle of subsidiarity underpinned our health system from 1938 to 2022

The principle is called subsidiarity. It has historical ecclesiastical origins, not always the best.

More important, for around a century, it has been the foundation of the relationship between local and central government internationally, including in New Zealand.

The underlying premise is that things should be done locally (or regionally) except when it is best done centrally.

But, in this relationship, central government is the ‘higher authority’ (just as the church was to families in the principle’s early ecclesiastical history).

Subsidiarity is also the principle that governs the relationship between the European Union and its member states.

Overwhelmingly healthcare is provided locally through general practices, non-government organisations, and hospitals.

Since the 1938 legislation, from hospital boards to DHBs, there has always been an influential level of statutory authority located closer to where most healthcare is provided.

Pae Ora Act 2022 ended principle of subsidiarity underpinning health system

The Pae Ora Act ended this principle of subsidiarity first by abolishing DHBs without any localised statutory alternative.

This meant the loss of a statutory local voice, at least behind closed doors, on behalf of geographically defined populations that DHBs were responsible for.

New Zealand already had, before their abolition, one of the most centralised health systems in economically developed economies.

It has now verticalised this centralisation by transferring decision-making further upstairs and far away from where most healthcare is provided.

The new entity Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora) was established in part to replace DHBs and to assume their roles for the provision of healthcare to their communities.

Health New Zealand also had transferred to it the Ministry of Health’s funding and planning responsibilities. It was formed by forced transfers of those who never chose to go there.

Further, the large majority of staff overnight had to adjust from district and horizontal to vertical accountabilities. The inevitable outcome, compounded by continual internal restructuring has been a stressed, confused and unhappy workforce.

Heather Simpson review abandoned

Despite Labour government claims to the contrary, this restructuring was not based on the preceding Heather Simpson led review of the health system established in 2018 and completed in 2020.

Heather Simpson’s review including continuing with the central roles of district health boards (ie, subsidiarity)

First, it overturned the review’s support for continuing with DHBs (ie, it abandoned the principle of subsidiarity).

Second, it radically changed the role of the proposed Health New Zealand by taking the huge additional operational responsibility for the provision, configuration and delivery of local healthcare that had previously been undertaken by locally based DHBs. This was never envisaged by the review.

Consequences

Andrew Little was the health minister who, by removing its underpinning principle of subsidiarity, substantially increased the poop that the health system is now in

With the absence of a cultural change to underpin this structural overhaul (other than a nebulous reference to health inequities), the restructuring was allowed to establish its culture. The restructuring was to verticalise an already centralised system.

In other words, whereas the Simpson review was about cohesion, the restructuring generated a culture of command and control.

The consequences include continuing the failure to address the impact both rising acute demand impacting on both general practices and hospitals and widespread entrenched workforce shortages.

Using business consultants to devise a new health system is like asking Wayne Brown to author a book on etiquette

The public health system we now have was largely devised by business consultants. This is akin to the wisdom panel-beaters designing traffic roundabouts or Auckland Mayor Wayne Brown authoring a book on etiquette.

The main beneficiaries are business consultants (or panel-beaters but perhaps not book publishers).

Compounding this fundamental error was the incompetent decision to restructure the whole health system in the midst of the pandemic instead of working to fix these key pressures on the system.

We now have a committed workforce that has been destabilised by substantial restructuring which has been poorly explained and lacks a convincing intellectual construct. It feels disrespected and devalued with the inevitable outcome of demoralisation.

Those closer to the ‘clinical frontline’ were already fatigued and many burnt out. Those further away from this frontline, but essential to its performance, are devalued and demoralised living in an environment of continuing job insecurity.

The restructuring initiated by former health minister Andrew Little (and Jacinda Ardern’s kitchen cabinet) is responsible for substantially increasing the poop that Aotearoa’s health system now finds it in.

Part Two of this blog will discuss how the health system might get out of the toxicity of this stench.

Ian Powell was Executive Director of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists, the professional union representing senior doctors and dentists in New Zealand, for over 30 years, until December 2019. He is now a health systems, labour market, and political commentator living in the small river estuary community of Otaihanga (the place by the tide). First published at Otaihanga Second Opinion.

How did our country get into the poop we now have poop everywhere in all facets. We have a poop government pooping on all but the sorted and they are about to poop on the environment more with their new RMA.

Greens/Labour get round that table now and agree to offer the voters meaningful, intelligent options to the status quo. It won’t be difficult but will require compromise, respect and the will to move NZ into a much better run country – it sure can’t get any worse! Our health system is in disarray, run by a Banker; our education system has been hi-jacked by another without educational capabilities or any consultation; our people have never seen such poverty with many fleeing; unemployment is rife and our lovely NZ is going to the dogs. If we continue down this CoC-up path, we will quickly be owned by another country. Is that what you want? There are no longer any controls – just lies, cheating, bullying and misinformation. So voters step up big time and actually comprehend what is really going on and the likely end results. Surely you must be able to see the majority of great decisions that have been adopted by NZ were Labour inspired and enacted – surely?

If anything, you are too kind to Andrew Little, who turned into a control freak when in government, while having no idea on how an effective health care system actually works. He seemed to be captured by the bureaucrats who wanted to build glass palaces and forgot who he was elected to serve.

Plus 1 to that comment.