This article was written by South African sports activist Mark Fredericks and gives an interesting insight into South African rugby which continues in 2017 to be riddled with racism and hypocrisy.

The lifting of the sports moratorium between 1991 and 1992, and along with it the retention of the springbok symbol for rugby has effectively reduced apartheid to a footnote. The bread and circus Republic of South Africa encourages the celebration of the inherent and structural inequalities in the country through sport. The elite sporting system in the country, which is built upon the foundations of the apartheid system of exclusion has been democratised allowing ‘undesirables’ into the system, after a suitable period of apprenticeship has been served within the incubators that served apartheid sport so well. The spiralling unemployment rate, which feeds the high crime levels, is exacerbated by a government that spends money on itself, and not on the needs of the people. Sport and mega events merely distract from the crises of a failed South African experiment. The first circus arrived in 1995 with the IRB Rugby World Cup, in 2003 the ICC cricket World Cup came and went, followed in 2010 by the FIFA Soccer World Cup – the bread however, has not. Now South Africa stands on the brink of hosting another circus in 2023. This celebration of inequality must be stopped.

SA RUGBY’S BID TO HOST THE 2023 RUGBY WORLD CUP TOURNAMENT.

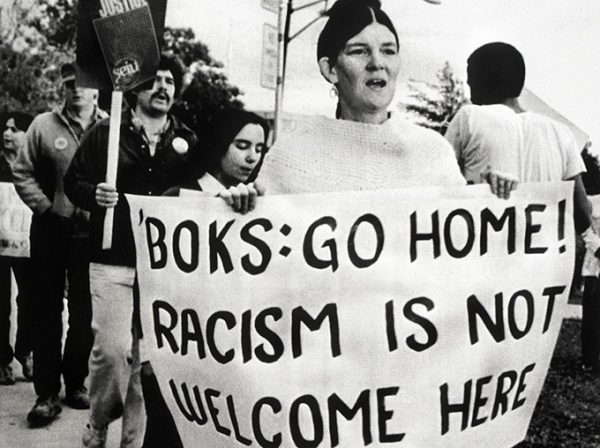

On the 15th of November 2017 the rugby nations of the world will vote on the hosting rights for the 2023 Rugby World Cup tournament. News reports indicate the South Africa has a good chance of becoming host for the second time, and expectations for success are high. Now it is no secret that the world rugby bodies strategically distanced themselves from the apartheid state, while supporting the racist South African Rugby Board. The SARB were never suspended from the International Rugby Board, and in 1989 the IRB even sanctioned an invitational team to play in the centenary celebrations of the SARB. During the apartheid era, the world rugby authorities ignored the legitimacy of the anti-apartheid rugby body in South Africa, choosing instead to work closely with Danie Craven’s SARB in efforts to normalise rugby relations in South Africa. In 1992 that normalisation was achieved, and upon Nelson Mandela’s personal petition, the reward was indeed great, and the 1995 Rugby World Cup tournament was awarded to South Africa. It was in this magnificent showpiece that the springboks were washed clean of all apartheid stains, and the green and gold emerged without apartheid blemish or racial taint.

The moment has been immortalised in John Carlin’s lopsided account of the tournament, and all that happened in uniting the nation in a memorable tournament of spectacular proportions. The world rugby authorities benefitted handsomely because it was the 1995 tournament that heralded the professional era, effectively killing the root of the game we all love. The tournament was the last time that rugby (any rugby) was to be seen on the public broadcaster in South Africa, as television rights deals had been sealed a year before the tournament even kicked off. Through this endorsement of the springbok, and the hailing of the apartheid heroes by the world rugby bodies – by inducting them into the World Rugby Hall of Fame (or is it hall of shame?) – World Rugby once again has displayed its disregard for the suffering of black people in South Africa. It regards the apartheid springboks as heroes, while totally ignoring the plight of those who struggled against apartheid through the game of rugby. And now, once again, the South African rugby hierarchy stands before the world presenting a case of mistruths, misinformation, and poverty pornography, as they bid for the rights to host the jewel of rugby tournaments in 2023 – the Rugby World Cup Tournament.

The World Rugby members would have watched a powerful 2 minute 25 second video clip which presented a vision of the country, that presents the face of South Africa as seen through the lens of Walt Disney. For those who missed the stirring presentation, here it is:

The video clip opens with a scene from a township – a common place of life and death for black South Africans. Originally designed as labour camps by Cecil John Rhodes, these cramped spaces are where black South Africans are mostly centred within urban areas. The normalisation of poverty and squalor is nothing to be ashamed of, and the way in which black faces are used when trying to sell rugby to the world brings back memories of 1995, when the face of Chester Williams adorned billboards all across South Africa.

As the video plays, the springboks bide their time before making their appearance, allowing for the sounds of Africa to call on the emotions of the viewer. The first scene, which shows a black player emerging from a shack, is accompanied by the sound of some African birdlife – a rarity in townships where there are no trees, and the most common sound would be the blare of hooters from thousands of taxis – and the sound of commuters on their way to work – even gunfire, but rarely birds. Without any shame, SA Rugby displays the lone rugby players’ stroll through the township, as he wends his way amongst dilapidated shacks. It is a place where he belongs, a township, surrounded by shacks, and death. The video clip does not show the recent call by the government of the Western Cape to have the South African army deployed in the townships, to combat gang warfare. The lone rugby hero thus faces a dangerous gauntlet if that scene was shot in Cape Town – our top tourist city. If you missed the news story, here it is:

The sound of an elephant in the distance heralds the arrival of a praise singer, as he stands on top of a mountain, crying out about Africa. The music and the visuals work together to tell an emotional story about a country that exists in the edit suites of the creators of the visuals, but not in reality. It is a projection of what is hoped for, not yet attained. The 1995 Rugby World Cup tournament yielded magnificent results for those upon whom the IRB/World Rugby body had already bestowed many blessings – the beneficiaries of apartheid. The promises of development faded as fast as a 5 – point lead against the All Blacks. The ZAR 2Billion television broadcast rights deal made the springboks and SA Rugby royalty wealthy, but it did nothing for rugby in the townships. The myth of white dominance of the game in South Africa was an easy myth to swallow, because the rugby unions of the world had always backed the white rugby horse in South Africa. For them the realisation that they had been playing in apartheid tests against an apartheid test team, which was sanctioned and recognised by the World Rugby body, was slightly discomforting. But the 1995 Rugby World Cup washed away not only the sins of the apartheid springboks, but also all of those teams who, through sporting contact, endorsed and supported apartheid rugby, and prolonged the life of apartheid.

The race to see the springboks back in international competition superseded any concerns or considerations of the deep physical and sociological aspects of apartheid. The race back into international competition even saw a smiling Nelson Mandela wave on team South Africa (Olympics, Barcelona 1992), months after the Boipatong massacre, as they marched without a flag, without an anthem, and with Mandela still unable to vote in any South African election.

None of these considerations are presented within the powerful video clip that everyone sat and swallowed emotional lumps over. The wording in the video declares:

Listen, listen…

Hear the sound of Africa.

It’s calling your name.

To a place where rugby is more than a game….

It’s a way of life.

Rugby is much more than a game. It is a tool that is used to conjure up fantastic social fantasies about a South Africa that does not exist in reality. The destruction of the social roots of rugby in South Africa, by the African National Congress and the rugby authorities in South Africa, coincided with the rebirth, or re-imagining of the springbok. The world rugby authorities threw their lot in with the elite establishments of South African rugby, no doubt mesmerised by the excellent track record of the integration of the game set by the racist South African Rugby Board. The players neglected by apartheid policies, who were never recognised by the international rugby bodies, have had their histories and cultures crushed under the weight of springbok mythologies. The townships depicted in the video clip, while used in a promotion of rugby as “a way of life”, are actually ghettos of death.

Where rugby united a nation,

And inspired the world.

Heed the call…

Come to the birthplace of humankind,

Wonderful words, wonderful sentiments, but far from being based in reality, these words are based within the realm of fantasy. Rugby did not unite the nation, it created the illusion of unity, and gave the media machinery enough visual fodder to repeat and reinforce the illusion, but unity was not attained. The birthplace of humankind actually holds the top spot as the world’s most unequal society, and this Monday past, there were protests against farm murders (actually a small percentage of the murder figures are from farm attacks), and it showcased the brittle nature of the rainbow nation. If any of you missed the story, here it is:

Where it all comes together.

Where rugby is number one.

South Africa.

Rugby World Cup 2023

What happened in 1995 was the normalisation of abnormality. It was the passing of the baton of inequality from white management to black management. The scenes from the video clearly showcase the pride with which our inequality is openly displayed. The Mandela years, which ran from 1994 to 1999, was the bloodiest in the history of the new South Africa with Interpol statistics recording 124, 564 murders (homicides) over that period (25,000 in 1995 alone). For some perspective, over the same period Ireland recorded 199 (1994 – 1999), and France recorded 5099. None of this has anything to do with springbok rugby of course, just as springbok rugby; despite being the flagship sporting symbol for an apartheid regime had nothing to do with apartheid. Sport and politics do not mix, except when the governments concerned are expected to dip into the coffers of taxpayer loot, and issue million dollar guarantees.

All, except the victims of apartheid, enjoys the post 1994 South African ‘sporting windfall’. Our disjuncture with reality, boosted by successes on the rugby fields in 1995 and 2007, further fuels the transformational delusion. As during apartheid, off field ‘tragedies’ rarely affected on-field performances; the weekend following the Marikana massacre the springboks faced off against Argentina in the Rugby Championship (18 August 2012) with no acknowledgement of the incident. A few days later, when facing Australia, the springboks observed a moment’s silence for slain boxing champ Corrie Sanders, (and Peter Maimane former Bok technical advisor) – despite not a single representative from SARU attending Maimane’s funeral.

Separating sport from other aspects of life in South Africa is an apartheid tactic, allowing for elite sport to be played in total isolation of the South African reality. The unification process was flawed through the assumption that ‘white‘ was right and better. The modality of the springbok production line has not changed. Springboks still come from the same elite schools, which produced springboks during apartheid, while township schools are routinely raided for the required racial quotas. The raided schools remain as squalid as they were under apartheid, these days just without their star rugby players, and the visuals are there in plain sight in the SARU visual presentation.

Judged on these criteria alone, the consideration of South Africa as a suitable venue for the 2023 Rugby World Cup tournament resembles the rebel tours of the 1980’s that prolonged the life of apartheid by giving the social order a semblance of normality. It is of further concern to consider that the IRB never apologised to the South African public for their endorsement of the racist South African Rugby Board, as well as their recognition of the racist springbok rugby team without any consideration of the players who were denied a playing and social space because of their unforgivable blackness. These endorsements gave then, as it does today, impetus to the continuation of the exclusionist nature of South African rugby development. It is utterly delusional to assume that the springboks are capable of holding the mantle of ‘Rainbow’ team, when the very ethos of the rugby system is based on excluding those denied by apartheid. Even the historical output in terms of books and biographies regurgitate the ‘glorious’ history of springbok achievement, while excluding crucial historical facts pertaining to the policies, which favoured ‘white’ players and denied ‘blacks’.

The IRB/World Rugby body has played its part in entrenching deeply rooted racial prejudices within South African society by recognizing apartheid sport, and the placing of apartheid heroes into a World Rugby Hall of Fame. The favorable consideration of South Africa as a preferred host candidate also showcases that it is indeed possible to enjoy ‘Normal Sport in an Abnormal Society’, as long as the abnormality does not affect the profits, and the glow of the social reputation of World Rugby. As the presentation video plays out, there’s a beautiful scene of a young girl running with a rugby ball under her arm as two young boys give chase. The video does not reveal that SA Rugby did not send a women’s team to the Women’s World Cup, which was held in Ireland earlier this year due to the state of the women’s game in South Africa. Not only that, but the state of the vulnerability of women generally in South Africa, whether a resident or a tourist, is cause for some concern. There are roughly 60 – 70, 000 rapes reported in South Africa annually. Many rapes are not reported because of threats, and the dismissive attitude of the South African police services. The little girl depicted in the visual does not point the viewer in the direction of the status of the female person in South Africa as a recent story about 87 young school girls revealed – for those who missed the story, here it is:

Now as we all know, this issue has nothing to do with rugby. The alleged molester was/is not a rugby player, but it depicts the normality, and daily reality of life far away from the pristine fields where the rugby matches in 2023 will take place. The tournament will lend credence to a social system that has failed the citizens this country on the whole, and after the tournament, as social conditions deteriorate further, those nation building springboks, as Pienaar and Venter did in 1995/6, will leave South Africa to further their careers abroad.

The entire post-apartheid society is built on the retention of apartheid privilege – as Mandela himself confessed:

“You must remember that the best way to introduce transformation is to do so without dislocating any aspect of our public life.

What is the role of the IRB/World Rugby body in recognizing the struggle against apartheid? Is it only to look after the welfare of the game at the extreme elite level? Does it not matter that the endorsement of racial and class divisions as embodied by the springbok and its overarching structure will inevitably lead to the downfall of the game in South Africa completely? And for that matter, in South Africa, the game is probably the least of our concerns. We have an economy that has been downgraded to junk status, yet our government has guaranteed millions for the tournament – as they did for the 2003 ICC Cricket World Cup, and the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup. The benefit has not filtered down to those depicted in the visuals, and yet the video presentation has leveled the playing field in a digital fantasy, bringing to life the vision of apartheid sages Verwoed and Malan, when they spoke about ‘separate but equal’, and allowing for the development of ‘each group according to their character and ability’ – in other words, ‘equality through separation’.

These are but some of the facts that I would like to bring to the attention of the World Rugby body members. I do so full in the knowledge that none of these issues have anything whatsoever to do with the game of rugby union, in the same way that the 2023 SA Rugby video presentation has nothing whatsoever to do with the realities of life and death, on and off the rugby fields in South Africa.

Mark Fredericks is a South African sports activist