Economist, author, and commentator Shamubeel Eaqub says he’s angry we’re building housing for the landed gentry and not enough affordable housing. The housing crisis has been building for decades, and it’s only going to get bigger over time if we don’t take action. At the recent Community Housing Aotearoa IMPACT conference, Shamubeel talked about what needs to happen to relieve New Zealand’s housing crisis.

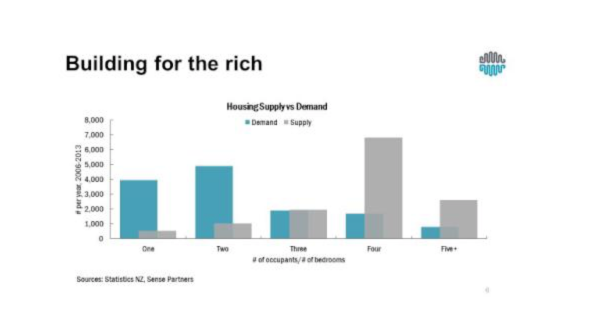

“We know the answer in a housing crisis is pretty simple – build more houses. But more specifically, we need to build more social and affordable housing. We’re pretty good at building large and expensive houses – we’ve got plenty of those, and that’s the problem.”

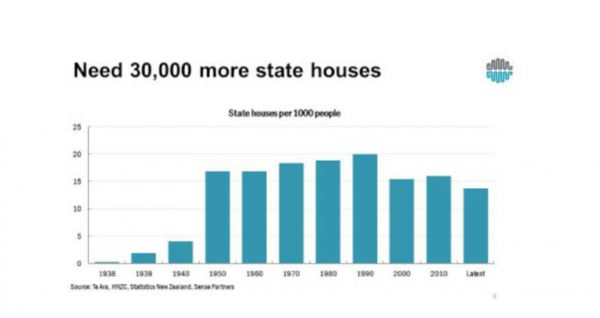

“I’m angry, firstly, that Housing New Zealand has been systematically neutered over the last 30 years and is now short of some 60,000 houses.”

The community housing sector, says Shamubeel, is far too small to meet the challenge of the shortfall resulting from the defunding of Housing New Zealand over the decades. Shared equity has to be one of the pathways New Zealand goes down to give people access to housing security.

“We know that inclusionary zoning in planning practices can have a positive impact in areas where we’ve mucked up affordability. We’ve seen it work in Queenstown, and there’s research now to show affordable housing doesn’t bring down the value of neighbouring properties.”

Fixed rentals need to be available for people who will remain renting in the future, he says. And we need to think about the lobbying we do as citizens to improve conditions for long-term renters because we won’t be able to provide ownership to everyone.

Shamubeel is generally angry that the social and economic consequences of the housing crisis are growing. He points to Auckland where social service workers can’t afford to live in the city anymore, let alone those in precarious living situations. He worries about what it means for New Zealand’s social fabric when we don’t care enough about what happens to half of New Zealanders.

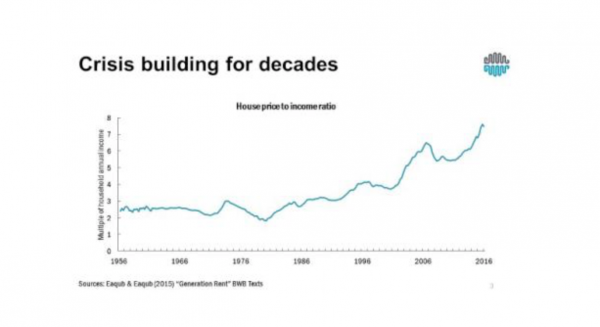

Shamubeel has plenty to be angry about: things have got much worse and this is not new, he says.

“House prices relative to incomes are higher than they have ever been before, and this has been rising for thirty-odd years.”

The consequences, he says, are mortgage slavery for those that can buy property and the rise of the landed gentry as we build for the rich.

“Houses are being owned by a smaller and smaller share of New Zealanders.”

Those who are renting are increasingly living in situations of poverty with no rights to security of tenure. They are suffering the consequent effects on household wellbeing, such as access to schooling.

These sorts of changes are going to cause generational discontent because of the generational gap in access to good housing.

“Housing shows the inequality that New Zealanders are experiencing – we are defined now by whether we are young or old, own homes or not. The reality is we need to build more houses to take account of the population changes we are facing but if you look at what we are building, they’re largely McMansions.”

It’s the buying and selling of houses that’s the problem, he says, and that we’re building for the rich.

“Profit-making housing providers aren’t the answer. They don’t want to build housing for poor people because it doesn’t make financial sense for them to do that.”

“The problem is that New Zealand has not been building enough houses overall since the 50s, 60s and 70s. The game that’s been running since the 1980s has largely been about the buying and selling of houses for speculative purposes.

“There would be no housing shortage if we had made the types of housing policies that valued supply of new houses for everyone in New Zealand, not just one part of the population.”

We shouldn’t be surprised that the supply side of the housing market is broken, he tells us. Profit-making housing providers are not the answer because they don’t want to build houses for poor people.

“There will not be housing built for poor people unless there is a public-good intervention – let’s not pretend otherwise.”

Shamubeel believes we need 30,000 more houses just to get us to the number of houses needed for Housing New Zealand, which hasn’t had any significant new build for decades. But there is no plan to get us there.

The number of building consents is decreasing, banks are turning back from lending for new housing, yet we have a housing crisis.

“It’s outrageous that we have a housing shortage, and yet we are going to have a downturn in building. A perfect storm is heading our way. We are about to face a housing bust over the next two years that is going to hurt like hell”.

Banks won’t be the answer in this storm as they become more risk-averse and won’t be looking at speculative building, or large and complex projects. They won’t be the solution for building more houses in the next 10 years.

Yet, there has to be other options in these constrained environments to help people get into secure tenure. We have to be very targeted, and the most immediate, most scalable, and the best tool in our toolkit is shared-equity programmes. But they would need to be scaled up significantly. Much better rentals are needed though Shamubeel thinks it will be hard to move from where we are as the political system is not yet ready for that.

“Given the significant bust we know we are going to face, we should be expecting a very counter-cyclical, fiscal stimulus of government spending, funded by borrowing to build lots and lots of state houses. That is the only credible solution to significantly increase the supply of social and affordable housing in New Zealand.”

We know from history and experience that capital grants for community housing will work, yet the lack of them is holding up development in the sector.

“There’s no moral leadership, and New Zealand will be characterised by a bust in housing in the next few years,” he says. “It’s only through government investment and capital grants that this will change. Our best chance is to work with local councils.”

The community housing sector has a big role to play in providing solutions. Influencing local government may be one of our best answers because local leaders can see that their citizens are suffering. We should be using inclusionary zoning to help close the gaps – it can be done immediately, and local authorities are deciding on their district plans now. We need to ask how we can access funds through the NZ Super Fund, Kiwi Saver, and global-equity funds to scale up shared-equity programmes.

“There is so much anger in me because I think we’ve left so much of this to boil over for so long. We’re too afraid to do more, but it hasn’t been enough to meet the needs of New Zealanders. We’ve got to do a lot more. We no longer have time to take things gradually – it’s time to sort out New Zealand’s housing crisis in a much, much bigger way.

We have to do something and we have to do it now, he says, and we need to stop thinking about the ‘us versus them’ and the ‘haves and have nots’ and get some more empathy into what is happening to people in New Zealand, and make a change.

Shamubeel left us with a quote from Martin Luther King.

“The urgency of now…this is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.”

Shamubeel Eaqub authored “Growing Apart: Regional Prosperity in New Zealand”, and co-authored “Generation Rent” and “The New Zealand Economy: An Introduction”.

States the problem but fails to see it.

What it means is the collapse of society as has always happened under capitalist regimes.

Again, states the problem but doesn’t see it.

It’s not the owners that are dropping into slavery but the renters who end up working hard their whole life for others to get more.

The problem is ownership and the way we allow that to provide people with income from doing nothing.

Banks, because they control the money in the economy, are part of the problem that causes our economy to be dysfunctional.

There are but they destroy capitalism.

Load of bollocks but that’s what I expect from traditional economists who haven’t woken up to the fact that the economy doesn’t work the way they were told at university.

The government never needs to borrow no matter how big its deficit:

The government never has a lack of money.

And we know from our own history that the government simply printing money and using it to build state housing works as well and that it’s cheaper.

No we don’t. In fact, NZ Superfund, Kiwisaver and global-equity all need to be canned because the hypothesis behind them is delusional.

Heard of CFT contracts? They are banned in the US and other places.

Here’s a trade idea you can hoop on. The moment you see CFT’s banned in your jurisdiction is the moment to go all in on proffesional learning platforms.

You can say thank you now.

Nope but that’s not surprising as the abbreviation could be any possibility of tens of thousands of combinations.

In other words, if you’re going to say something you should make it clear just what you’re actually talking about otherwise people will just assume that you’re an idiot.

O,k. Ok. Ok. Here’s an easier one.

for one million standardeesta +1millionz.

Do you know what a CFD contract is?

Riiiight, so you’ve still got nothing to say.

Oh then. I give up :D:D:D 8p-)

Ps. Precious earth is a rear commodity NZ could never collect enough to deny access to New Zealand’s sea lanes.

Comments are closed.