The Nonsense of the Knowledge Based Curriculum

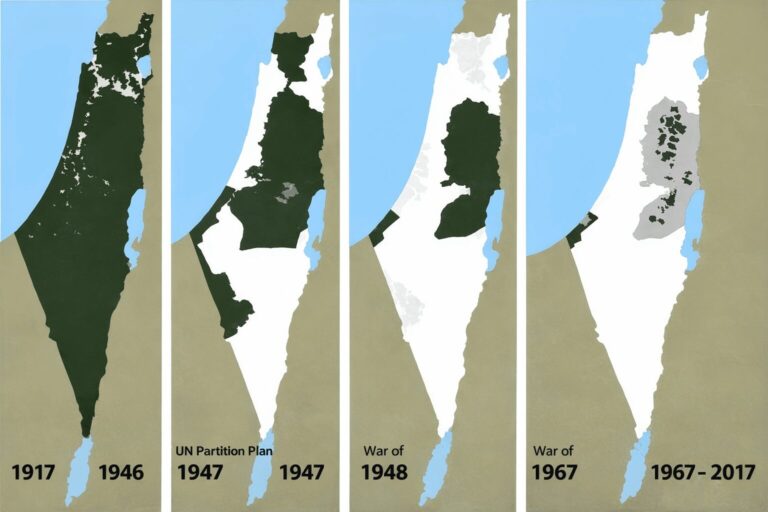

One of the mantras of the current government’s education policy (or, more precisely, Erica Stanford’s education policy), heavily based on the beliefs of Dr Michael Johnstone and Dr Elizabeth Rata of the New Zealand Initiative, and beyond that, the Atlas Network, is the ‘knowledge based curriculum.’

This immediately raises many questions, the prime one being what knowledge are we talking about?

Knowledge as defined by the neoliberals is going to be vastly different than the knowledge defined by those with a different world view.

Knowledge defined by people with a very strong Anglo-Saxon bias is different from knowledge defined by people with an European bias, let alone those with an Asian or Pacific or New Zealand world view.

Which of these is correct?

Knowledge defined by those who believe in the values of 19th century England (Elizabeth Rata) is different from those who believe in knowledge that meets the needs of the 21st and 22nd century.

Further, much of what is called knowledge is not fixed, it is always subject to reinterpretation and revision, so there is no absolute knowledge over time, other than at a very basic level. This is not to say that children shouldn’t learn basic principles e.g., in science and mathematics, but we need to be mindful that much of what we believed in the past was overturned by new discoveries.

The danger here, and I believe that this is very much the case with Erica Stanford’s vision, is that the knowledge which is identified as necessary for children to learn is selected on an ideological basis. You may not be uncomfortable with that, however put the shoe on the other foot, and ask yourself how comfortable you would be if the defined knowledge did not fit in with your world view. Mandating knowledge, other than basic principles, is a slippery slope towards mind control.

Another factor to be considered is the sheer quality of knowledge in the world. Either the knowledge based curriculum is forced to select what knowledge is essential, using what criteria? Alternatively the curriculum will be so full of knowledge it is impossible to teach and even more impossible for children to learn.

It sees that the Ministry of Education, being subject to Ministerial requirements, is struggling to put together a coherent knowledge based curriculum.

This article spells it out and I will comment on sections of it.

Not much logic in draft curriculum’s sheer amount of ‘knowledge’

‘There’s no question a lot of ‘knowledge’ is covered in the material. Indeed, the greatest barrier to teaching the new curriculum is the sheer quantity of knowledge that students will need to learn each year. Across all subjects, content is divided into year levels – each packed with key’ knowledge’ that needs to be taught.

For example, in the first year of schooling there are more than 80 learning objectives – covering knowledge areas and associated practices – just in the new maths curriculum.’

This takes me right back to the 1990s when the curriculum documents were overloaded with achievement objectives, and schools were stretched trying to cover them all. They had no option as the Education Review Office would descend at three yearly intervals to demand evidence that the curriculum was being implemented.

Failure to provide this brought with it a possibly that the school would be found to be non-compliant. Back in those days, newspapers were able to access and publish ERO reports and that was something schools wanted to avoid at all costs. Shame and blame was deemed to be a way to ensure schools complied.

The need to cover such a number of learning objectives also brought with it a couple of big negatives, both detrimental to children’s learning. The first one being that teachers could only spend a couple of weeks at most teaching a particular unit, for example in Science, before having to terminate that and move on to the next one.There was insufficient time to do anything but a once over lightly teaching and learning programme.

The second one, that used to really bother me as a principal, is that teachers were so busy focusing on getting through the scheduled teaching programme, for which they were accountable, that they didn’t have the freedom to make use of unplanned significant events which often provided the basis for impromptu learning experiences – experienced teachers will know that these are often the most successful and enjoyable learning opportunities for children.

I recall a day when mid afternoon one winter, it started snowing heavily for about an hour, this was most atypical of the area and was something the children had never experienced. How many teachers dropped what they had planned and immediately planned learning opportunities about the snow for the children? None. Too busy working through the curriculum to drop it for real learning opportunities.

‘Add to this that an estimated 50 percent of primary schools have multi-level classes, which means teachers will need to juggle a set of knowledge with half their class and a different set with the other half. Previously, this could be addressed by choosing topics that could be studied by multiple age groups – but this won’t be possible now.

Someone has no idea about how teaching and learning works in multi-level classrooms.

However, consider this next section in light of my previous comments about selecting which knowledge should be included.

‘Then there’s the ‘logical order’ problem. In the draft science curriculum for year 1, an example of the sort of knowledge five-year-olds are logically required to know is “Theophrastus (c.371–287 BCE) described plant forms and structures. His botanical texts were used for centuries as primary references”’.

Five year olds are expected to learn that? Why?

Try this:

‘Or we can look at the history strand of the social sciences curriculum. A (logical?) decision has been made to start in the distant past and then move forward. Under the title ‘The first humans’, five-year-olds will learn that “Homo sapiens evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago. They used tools and fire and lived in groups”’.

I’ve known some pretty smart five year olds, however that it would have been way beyond their developmental stage.

‘I find it amusing that, in the same year, children will learn in maths “A sequence of events can be described using everyday language (e.g., before, after, tomorrow, yesterday, next, and last)”. If they are struggling with yesterday, how will they understand 300,000 years?’

Who exactly is writing this stuff?

Now to reinvent the wheel:

‘As the ministry’s website says, “The science of learning is the study of how people learn”. The science of learning tells us students learn best when they feel safe, when they are well fed, when they can connect their learning to their experiences and what they know, and when they have a chance to revisit previous learning to embed it in their memories.’

Ok, can someone please tell me how many five year old children can connect learning about homo sapiens to their previous learning experiences? I’ll wait.

‘For example, in the two hours a week teachers will have to dedicate to the four strands of the social sciences, year 4 children (nine-year-olds) will learn (under the heading ‘Military and warfare’) the “importance of hoplites” and the “significance of key battles in the Persian Wars (Marathon, Thermopylae, Salamis)”’.

Naturally all nine year olds have the experiential base to connect this learning to existing learning. And naturally this knowledge will be essential for the rest of their life.

Or alternately, ask yourself why it was deemed that this deemed essential knowledge? Or who was responsible for including this? Elizabeth Rata, by any chance, the academic who believes in 19th century classical education?

Science is no better.

‘Likewise, in year 2, students will learn “materials take up space and have mass” and that “mass is the amount of matter present in an object”. I challenge you to take a minute to think about defining mass and matter, and the difference between them, to a six-year-old in a way that sticks in their long-term memory.’

I’d be prepared to wager that a significant proportion of adults couldn’t define the difference between mass and matter, even if they learned it at some stage during their secondary schooling, let alone as a 6 year old.

‘Instead of delivering a logically ordered curriculum grounded in science, it would seem the new curriculum does the opposite. It is badly organised, illogical, and there is too much ‘knowledge’ – some of it random – for students to be able to build on their previous learning.’

It appears to me that this curriculum is being written without any consideration for how children learn, the way learning differs for children of various ages. Expecting a 5 or 6 year old, who is most definitely not able to handle abstract concepts, to learn and understand about the difference between matter and mass, is ridiculous. I’d argue that this would stretch the average 12 year old.

Do these people have any understanding of pedagogy, of the developmental stages children go through?

And we need to be mindful that this is the so-called ‘tip of the iceberg’. What else is there to come?

It is also apparent that the authors, and more particularly those behind this, have no understanding of memory, especially how things get fixed into long term memory.

A little test to ask yourself – how much do you remember of all the things you learnt in your schooling, both primary and secondary? Get the point?

As Einstein wrote:

‘’The wit was not wrong who defined education in this way: ‘Education is that which remains, if one has forgotten everything he learned in school.’

There is so much wrong with Erica’s education agenda. I (and others) can keep pointing this out, however it is up to all of you to fight back.

It will be current and future children who will pay the price.

Are you happy with that?

Dropping a tennis ball and cricket ball on your foot would be an easy way to explain mass and matter. I’m not sure if dropping them on a foot would be politically correct though.

“The science of learning tells us students learn best when they feel safe, when they are well fed, when they can connect their learning to their experiences and what they know, and when they have a chance to revisit previous learning to embed it in their memories.”

The problem with revisiting previous learning is children don’t have much previous experience and memories to create those connections. You have to jump start knowledge by simply accepting starting presumptions, and knowledge that has to be force fed — basic vocabulary, basic maths, times tables.

Its like a very well known MMA coach said, at the beginning of your training he’s going to be a fucking dictator, just do as he says. and drill and train the core skills. After that the expression comes. This does not mean no fun, times tables can be made competitive. But even if it is not fun, that’s not the purpose of education. The goal of education is to embed skills for survival.