GUEST BLOG: Tadhg Stopford – RBNZ confessions

The Reserve Bank of NZ doesn’t decide what Money builds

New Zealand doesn’t have a monetary policy problem. It has a credit governance problem.

New Zealand has become what Bernard Hickey calls a “housing market with bits tacked on.”

That description is accurate. What is missing is the cause.

Because this outcome was not an accident of markets.

It was the result of a change in the rules.

There is a quiet error at the heart of our economic debate.

We are told the Reserve Bank controls the economy through interest rates.

We are told, that by adjusting the Official Cash Rate (OCR), it can raise or lower inflation, cool or stimulate activity, and steer outcomes.

That framing is neat. It is also wrong in a way that matters.

Because the Reserve Bank does not decide what money builds.

Start with what the OCR actually is.

The OCR is a short-term policy rate. It is an anchor. A signal. It influences the financial system.

But it does not set the full price of borrowing.

As the Reserve Bank itself acknowledges, lending rates are shaped by a wider structure:

- offshore wholesale funding costs

- bank balance sheet constraints

- risk margins and competition

- regulatory capital rules

The Reserve Bank moves the reference point. Markets and banks determine the actual price.

Even on its own terms, control is partial.

And even then, price is only part of the story.

Because the more important question is not:

What does money cost?

It is:

Where does money go?

In modern economies, most money is created by commercial banks when they lend.

The Reserve Bank itself is explicit on this point: banks create the majority of money through credit creation.

That means:

Banks do not just intermediate money. They create it — and allocate it.

And they do so according to incentives:

- collateral availability

- regulatory treatment

- risk-adjusted return

The Reserve Bank also acknowledges something else:

It does not direct that allocation.

That sits with private institutions.

In New Zealand, those incentives overwhelmingly favour housing and existing assets.

So the system works like this:

The Reserve Bank sets a reference rate. Banks create the money. Banks decide where it goes.

And what it builds is largely outside public control — or strategic national interest.

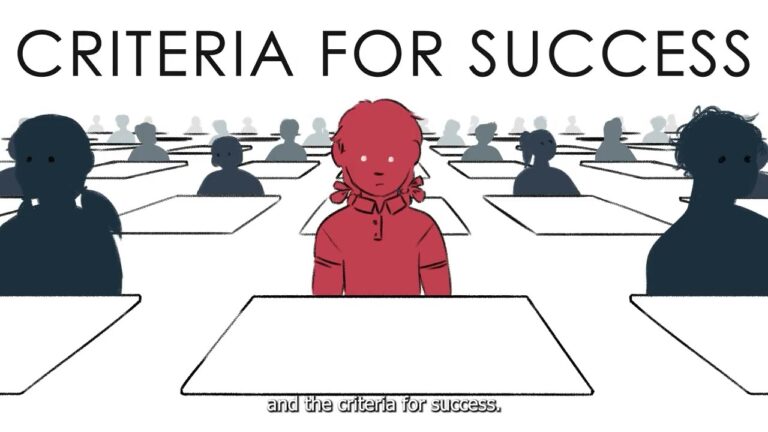

Now consider how success is judged.

Monetary policy is anchored to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This is the metric used to define inflation, and therefore success.

Again, the Reserve Bank is clear: CPI is the target.

But CPI does not measure the full cost of living.

It excludes house price inflation. It does not capture the lived weight of financing costs. It is designed for consistency — not completeness.

Alongside it sits another measure: the Household Living-costs Price Index (HLPI).

HLPI tracks what households actually pay — including interest costs and essentials.

The divergence between these measures is now well documented.

Which creates a structural blind spot:

Policy can succeed on CPI while households experience rising pressure.

Now look at how adjustment actually happens.

When inflation rises, the OCR increases. Borrowing costs rise. Household cashflow tightens. Demand slows.

Eventually, CPI falls.

This is the mechanism the Reserve Bank describes.

But the path is not neutral.

The burden of adjustment falls disproportionately on households — especially those with debt. Meanwhile, the structure of the economy — what is built, where capital flows — remains largely unchanged.

Inflation is reduced. But capacity is not necessarily increased.

The system stabilises itself. It does not necessarily improve itself.

Put the pieces together.

The Reserve Bank influences the price of money, but does not determine it. Banks create credit and allocate it based on private incentives. Policy success is judged using a measure that does not fully reflect lived costs.

These are not contested claims.

They are embedded in the system’s own description of itself.

And the outcomes are not mysterious.

Credit flows into housing. Asset prices inflate. Household debt rises. Productive investment struggles to compete. Essential costs remain under pressure.

These are not failures of effort.

They are consequences of design.

That design has a history.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, New Zealand rewrote the legal architecture of its economy.

Through reforms to:

- the Reserve Bank framework

- the Public Finance system

- state asset structures and mandates

what had once been a more integrated model of public finance and development was replaced.

Sovereign credit creation and allocation were no longer normal tools of government.

Price stability — defined through CPI — became the central organising principle.

The state was fragmented into agencies with narrow mandates, rather than a unified balance sheet with developmental purpose.

And critically:

The question of where credit should go was left largely to private balance sheets.

This is what is often described as “Ruthenasia.”

Not simply a set of policies.

But a shift in the constitutional rules of the economy.

From that point, the trajectory is not hard to follow.

If the state does not allocate credit, and banks are incentivised toward asset-backed lending,

then credit will flow into housing.

If inflation is measured in a way that excludes asset prices and underweights financing costs, then that dynamic will not be fully visible in policy.

If adjustment is achieved through interest rates, then households will absorb the burden.

The system did not drift into its current form.

It was legislated into it.

None of this requires conspiracy to explain.

The system is internally coherent.

It prioritises:

- price stability as measured by CPI

- financial system stability

- decentralised credit allocation

Within that framework, the results follow.

But systems are not sustained by tools alone.

They are sustained by incentives.

The current framework produces stable signals. It maintains institutional credibility. It aligns with global norms.

And it distributes responsibility in a way that is difficult to challenge.

No single actor controls outcomes. No single metric captures the full picture. No single decision appears decisive.

That diffusion is not accidental.

It is what allows the system to persist.

Around it sits a network of aligned incentives:

- banks whose balance sheets benefit from asset-backed lending

- advisory and consulting ecosystems aligned with existing frameworks

- regulatory and policy careers built within the current paradigm

- international institutions reinforcing common standards and constraints

None of this requires coordination.

It only requires alignment.

In that environment, change becomes difficult not because the system is hidden, but because it is normal.

The language is familiar. The metrics are accepted. The outcomes are explained rather than questioned.

And the gap between what is measured and what is lived is treated as noise, not signal.

This is the real constraint.

Not a lack of intelligence. Not a lack of data. Not even a lack of tools.

But a system of incentives that rewards continuity and fragments responsibility.

Which brings us back to the central point.

The Reserve Bank influences the price of money, but does not determine it. Banks create credit, but allocate it according to private incentives. Measurement defines success, but does not fully reflect lived reality.

And the surrounding institutional structure makes this arrangement stable.

So the question is not whether the system works.

It does.

The question is:

Who does it work for, and what does it build?

Because a country is not shaped by how carefully it stabilises its indicators.

It is shaped by whether its systems are capable of:

seeing reality clearly, directing capital deliberately, and taking responsibility for the outcomes.

At present, we do the first partially, the second indirectly, and the third not at all.

That is not a technical problem.

It is a constitutional one.

And until it is addressed as such, the system will continue to function as designed—

producing outcomes that are predictable, defensible, and increasingly difficult to live with.

The system is not broken.

It is delivering exactly what its incentives produce.

RBNZ interview referenced: https://youtu.be/IE8EQnOBqqw?si=CcTBIxWEsuPRzGFS

Tadhg Stopford is a historian and teacher. Support change by purchasing your CBD hemp CBG at tigerdrops.co.nz