Education is much more than ‘The basics, done well’.

The debate over “the basics” in education has intensified in recent years. While literacy and numeracy are undeniably foundational, the question remains: is schooling simply about minimum competency, or about unlocking the full potential of every child? This article explores that tension through history, policy and contemporary debate.

In a comment on my recent article “New school year, new educational nonsense”, Mark wrote’

‘If we get the three Rs right and nothing else, students will at least leave school equipped with the skills to be productive citizens and get a decent job and contribute to society.

The problem there is an issue with the three Rs at the moment and that is where massive focus should be directed. I have seen it first hand in students not even being able to get direct access to polytechnic engineering programmes because of inadequacy in this areaThe other 10% to 20% is a nice to have, but let’s concentrate first on getting the basics right.

You appear not to deny the importance of the three R’s and I don’t deny the importance of a well rounded education. But much of the remaining 20 percent relies on competency in the three Rs.

My daughter did a philosophy degree along with her commerce. She loves literature and philosophy, developed from being an avid reader from her very early years. The enjoyment of reading naturally arises only if one has the ability to read well. At the same time while not being exceptional at maths, and not being much interested in it, she has firm capabilities in numeracy developed at high school (she want to an excellent school that concentrated on this, she did Cambridge exams) and this has served her well in her finance career.

Are these not the kind of opportunities you want for all students, regardless their socio economic background? Yet they are readily achievable without requiring a huge amount of resource, so long as the dedication is there among educators.

The Soviets and Chinese communists, regardless of whatever else you think of them, achieved spectacular results in raising literacy levels in their respective countries, on far fewer resources than we in what is still one of the wealthiest countries in the world. This laid the essential foundation for industrialisation.’

The Three Rs: Necessary but Not Sufficient

It’s nice to read a well thought and reasoned comment like this, as it provides a platform for discussion to explore the issue further.

Quite obviously, competence in reading, writing and mathematics is a prerequisite foundation for everything in life, and I’ve never written otherwise, nor has any reputable educator. This has always been the case in New Zealand education.

Mark’s comment thought that students need at a minimum to ‘leave school equipped with the skills to be productive citizens and get a decent job and contribute to society’ needs to explored a little further. This is a minimalist goal, certainly necessary, but in my opinion falls short of a more lofty aim, that was very expressed by the first Labour government (although written by the the then and very visionary Director of Education Dr. Clarence Beeby),

Clarence Beeby and the Vision of Education as a Right

“The Government’s objective, broadly expressed, is that all persons, whatever their ability, rich or poor, whether they live in town or country, have a right as citizens to a free education of the kind for which they are best fitted and to the fullest extent of their powers. So far is this from being a mere pious platitude that the full acceptance of the principle will involve the reorientation of the education system.”

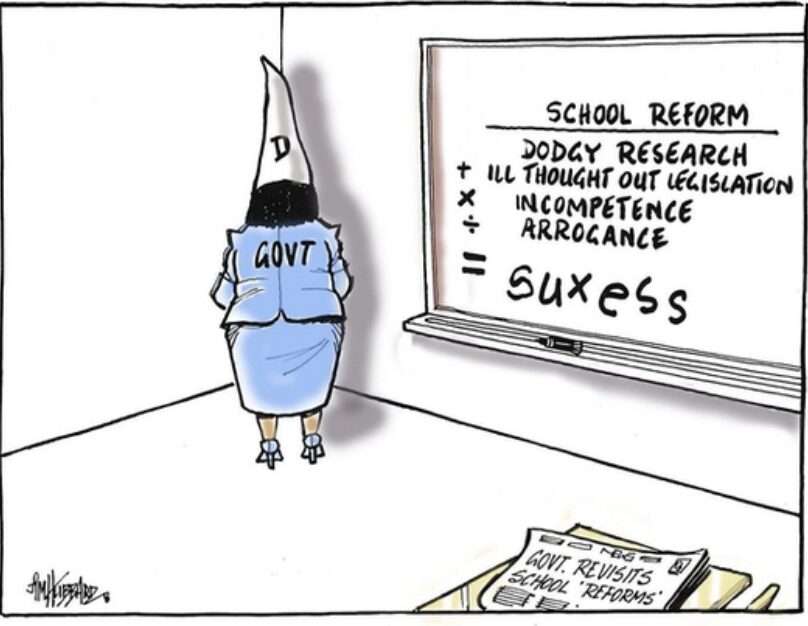

Compare that vision to the catch phrase of ‘the basics done well’ that is the current government’s policy. The major concern is that the basics at all costs focus will limit children’s education and achievement of their full potential. And to repeat the point I made earlier, this does not state or even imply that competence in the basics isn’t important.

Are Literacy Standards Really in Crisis?

Mark also says that “there is an issue with the three Rs at the moment and that is where massive focus should be directed.” Yes and no, actually. The issue isn’t as bad as is being made out, but there’s no political advantage in admitting that. Yes, things can always be better and continual efforts need to be made to achieve this. How doing away with literacy specialist teachers, as the government has done, is going to assist with this is beyond me.

‘For Caroline Morritt, a former specialist literacy teacher, 2026 is about pivoting to a new working life after a Government decision to disestablish the role she loved.

Morritt spent the past eight years as a resource teacher – literacy. Employed by the Ministry of Education, she supported primary school students – including those with significant learning difficulties such as dyslexia – to read and write and provide professional development for their teachers.

She gained a masters degree in literacy over four years while in the role and supported 20 primary schools across Banks Peninsula and southwest Christchurch.’

Actually, the reason for dispensing with reading experts is quite clear – while as in Caroline’s case they are highly qualified in literacy, their approach does not fit in with Erica Stanford and the New Zealand Initiative’s ideology of structured reading.

“Ministry of Education acting deputy secretary (curriculum centre) Pauline Cleaver said professional development for teachers in structured literacy – an evidence based approach to teaching children how to read and write and mandated for schools from 2024 – would be delivered by 15 private providers contracted by the ministry.”

Note the move away from Ministry of Education employees to the private sector. Once we were told to worry about professional capture, now we really need to be worried about the creeping privatisation of education.

Inequality: The Real Driver of Educational Disparity

The ‘elephant in the education room’, that a right wing neoliberal government will want to ignore at all costs, is that the most dominant feature of children’s educational achievement is inequality and especially poverty. This has been established by numerous educational research programmes, in New Zealand and overseas. Differential funding of schools, based on the socio-economic backgrounds of their students, acknowledges this, but it still avoids admitting the real issue – poverty and everything that goes with it.

A government that was truly concerned about educational disparity would invest heavily to ensure that poverty and inequality/inequity is addressed, except that according to the Prime Minister we can’t have that, because it is socialism.

Until the socio-economic issues are addressed then educational disparity will remain. The minimal efforts made by the last Labour led governments to address childhood poverty, while better than nothing, won’t have made an iota of difference. Comprehensively addressing this issue will require a complete overturning of current economic ideologies, something way beyond the scope of this article.

Mark wrote:

‘Are these not the kind of opportunities you want for all students, regardless their socio economic background? Yet they are readily achievable without requiring a huge amount of resource, so long as the dedication is there among educators.’

Yes, that’s what the Labour vision said, however the big proviso is that dedicated and committed teachers (by far the great majority – there are very few who don’t give their all to doing their best for their students) don’t have a magic wand and can not undo the problems caused by home background issues.

There was an article the other day about the problems schools are having with the unpreparedness of children to start school at 5 years of age – that was becoming an issue 15 years ago before I retired, when principals started asking their colleagues about the problems with their new entrant children. It seems this has gotten worse – for example five year olds arriving still wearing nappies, not because of medical reasons, but due to poor parenting. Unruly behaviour is another one, children who are out of control and who seemed to have never had to learn how to behave. I could tell you some horror stories about how children were treated at home and how they arrive at school.

When you compare these children to those who arrive very well prepared for school then the achievement gap is already a gaping chasm and in spite of schools and teachers’ best efforts, usually impossible to close. Mark’s daughter clearly has done well, I’d suggest that much of the credit for this should go to her parents for providing her with the foundational attributes necessary for her to succeed at school and in life.

Revisiting the Beeby Vision in the 21st Century

Back in 2003, Steve Maharey, who later became by far the most knowledgeable and visionary minister of education this country has seen since Peter Fraser, delivered a speech entitled The Beeby Vision Today.

I’ll highlight selections; however I really encourage you to read this for yourself; and while doing so, run a mental comparison of Maharey’s erudition against Education Minister, Erica Stanford.

‘Beeby was a visionary thinker. His famous quote establishes a public good and right-of-citizenship basis for the education system.

It was, in this sense, an inherently social-democratic statement (even if Beeby had originally conceived of it as a social rather than political vision).

Beeby’s vision formally commits the state to enabling every child, each citizen, to reach their potential.

Stated simply, it was about, as he put it, “making the education system responsive to the needs of the individual kid.”’

The background to this statement:

‘The First Labour Government, with Peter Fraser as Minister of Education, had already initiated sweeping changes. It had readmitted 5-year-olds to school, re-opened the training colleges, set up the Council of Adult Education and begun an ambitious school building programme.

Perhaps most symbolically, Fraser had in 1936 abolished the proficiency examination at the end of standard 6.’

And:

Apart from noting how the Beeby statement actually developed it is worth recalling what education was like at the time.

“If we take a historical snapshot of the education sector during the early post-war period we can see that while the idea of equal opportunities was strong, in reality only a small group of New Zealanders progressed through to upper secondary schools and further education.

Nearly 3,500 children were in kindergarten;

Close to 275,000 in primary education;

Just over 50,000 in secondary education;

18,700 in trades training; and

Close to 13,000 attending university to which students could go if awarded a place.

The system was dominated by a series of examinations. University Entrance, previously supreme, was now joined by School Certificate. Those that made it through both would go on to University.

As the difference between the numbers attending primary school and secondary and those in further education shows, the system was based largely on a ‘sorting out’ strategy.

The system still operated very much as a series of filters, providing for each individual the point at which they should conclude their educational experience.

As people exited the education system they moved off to find a role for themselves in a low skill, low wage, commodity producing economy. For the majority of women, of course, this meant work in the home.

Much of Beeby’s effort was devoted to ensuring that those filters worked in the fairest way and did not ‘sort’ people out of the system prematurely.’

I discussed this sorting approach in my previous article ‘Reindustrialising Education, Taking It Back to the 19th Century’

Having discussed the history, Maharey then focussed on the needs of today’s children as they prepare for life in the 21st century.

Since that speech in 2003, we now need to consider the needs of many children being born now who will see the 22nd century. Do you think Erica’s vision goes that far? How will reindustrialising education meet their needs?

‘The kind of society our education system serves is also very different.

Our overall goal as a nation is to lift our skill and knowledge base to equip all New Zealanders for the demands of the 21st century.

This includes coming to grips with what it means to live with the new technologies that are central to the information age we live in.

The education system needs to respond to the distinct expectations and aspirations of Maori communities and individuals. This is not simply a matter of ensuring that Maori get the same educational opportunities as Europeans. It is often a matter of developing new programmes and providers.

Increasingly, Pacific Island people are also demanding more from education, both in terms of opportunity and in terms of offerings that reflect their own experiences.

The education system is critical to meeting the hopes and dreams of new migrants as well. It can be the key to their successful settlement in New Zealand.We also have a different kind of economy now. We are no longer an offshore farm for Britain. We have needed to, and still need to, build a new economy to meet different global circumstances. This means adding value to goods and services while developing the systems that allow us to constantly innovate.

Literacy and numeracy are now essential for all New Zealanders.

We need as a society and individuals to be able to respond to environmental challenges not faced by previous generations.’

Education for the 21st — and 22nd — Century

Looking ahead, Maharey set out the following goals for New Zealand Education:

Two months ago the Government released an overarching policy statement, Education Priorities for New Zealand.

The document begins by referencing Beeby’s vision. It then sets out two key goals for the education system.

The first goal is:

An education system that equips New Zealanders with 21st century skills.

This goes well beyond narrow technical skills. We are talking about skills that focus on creative and innovative thinking, and skills that will help us to relate to each other.

The second goal is:

To reduce the inequalities in educational achievement to ensure that all New Zealanders can reach their potential.

Our education system produces good results on average, and our highest achievers are amongst the best in the world. But there are too many New Zealanders that the system does not yet work well enough for.’

Maharey goes on to outline the then Labour led government’s plans to implement this. Read this for yourself and as you do so, compare it to the a significantly narrowed educational vision of the current and past National led governments, and to the prescriptive ‘one size fits all’ back to basics approach of Erica Stanford, the government she represents and of the ideologically based agenda, sourced from overseas, that underpins it.

The contrast between these visions is stark.