Analysing Ukraine: Starlink down, Ukraine attacks

The land campaign is evolving quickly, primarily driven by Russia’s recent communication problems: the loss of Starlink, and their decision to ban Telegram. The impact of these issues is greater fluidity on the frontline. Ukraine taking advantage of Russia’s problems to mount local attacks, and Russia taking advantage of Ukraine’s re-positioning of forces to mount their own offensive operations. It is a rapidly evolving and interesting period that highlights the important role of digital communications on the modern battlefield.

Meanwhile, NATO’s Ukraine Defence Contact Group meeting at Ramstein on 12 February confirmed a US$ 38 billion aid package for Ukraine. A demonstration of Europe’s continued commitment to support Ukraine’s campaign.

Ukraine’s new Defence Minister Mykhailo Fedorov provided noteworthy insight into discussions at Ramstein, and into Ukraine’s plans. Federov confirmed Ukraine’s strategy when he wrote on X that “The president set a clear task for the Defense Ministry: build a system to stop the enemy across all domains — air, land, and sea — and strike the aggressor’s economy asymmetrically.” Ukraine’s approach to the first objective; stopping Russia on land, in the air and at sea is to pursue automation. Ukraine aims to leverage its tech advantages to build better surveillance, digital communication networks and drones that can offset Russia’s ‘mass.’

Although Ukraine’s programme is currently focussed on defence there are indications that in the longer-term Ukraine is keen to transition this technology into offensive operations. The Kyiv Independent observing that “At the Ramstein meeting Fedorov presented 18 strategic defense projects planned for 2026, including expanded funding for domestically produced missiles and the creation of specialized drone assault units.” A transition that Ukraine has already managed in the naval battle, and that it is starting to experiment with in the ground battle.

Ukraine’s second objective, striking Russia’s economy asymmetrically involves a combination of long-range drone and missile attacks on Russian oil infra-structure, including tankers. It also includes an information campaign to encourage other nations to limit the activities of Russia’s ‘shadow fleet.’

The meeting at Ramstein was followed immediately by the Munich Security Conference, the world’s largest annual security conference. Although, Ukraine’s President Zelensky attended and met with US Vice President JD Vance, the most important activity was on the conference floor where attention focussed on Vance and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s speeches.

Vance and Rubio, both reinforced the Trump administration’s position on Europe. Vance aggressively and Rubio in a more measured and placatory tone but the message is clear; that US support for Europe is now conditional and less certain. The Brussels Times observing that “Today, as leaders again gathered at the Munich Security Conference over the weekend, the uncomfortable truth remains unchanged. The tone in Washington may fluctuate, but the strategic direction does not: Europe will increasingly have to rely on itself for its security.” A very uncomfortable position for NATO and for Ukraine, especially as this week’s tri-lateral peace negotiations in Geneva ended without tangible results. The BBC reporting that “Talks between Russia, Ukraine and the US aimed at ending Moscow’s war in Ukraine have concluded without a breakthrough.”

The strategic situation

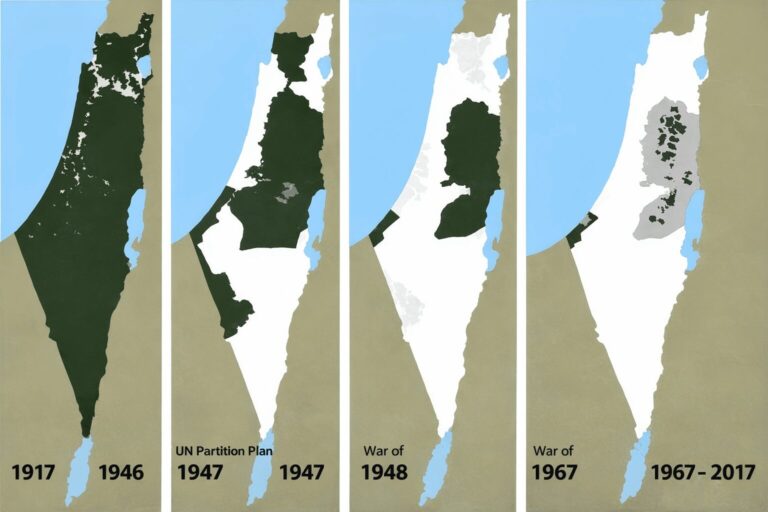

At strategic-level two trends are hardening into facts; that Russia is not ready to negotiate and that the US is unlikely to increase support to Ukraine. The assessment that Putin is unwilling to negotiate was recently supported when Reuters reported discussions with key leaders in the European intelligence community. The article anonymously quoted one national intelligence chief’s assessment that “Russia is not seeking a peace agreement. They are seeking their strategic goals, and those have not changed.” The article also points out the difference between the optimistic talk of US negotiators and the realistic assessments of European intelligence chiefs.

Russia’s unwillingness to discuss a ceasefire is influenced by US policy because only America has the war stocks and defence industrial base to immediately defeat Russia. If the Trump administration decided to put US muscle behind Ukraine, it is likely Putin’s position would change.

Putin’s strategy – to outlast Ukraine’s supporters – is incentivised by current US policy. The Russian military is still powerful enough to continue its slow, ‘broken backed’ war against Ukraine for the foreseeable future. A situation that US aid could change immediately because American war reserves and defence industry capacity is so much larger and more easily deployed than NATO’s. However, the once powerful Russian army is a shadow of its former self. Now Russian soldiers creep forwards using old tanks, civilian vehicles and mules, maintaining a painfully slow advance that Putin ‘spins’ into a narrative of inevitable victory.

The counters to this strategy are to either; inflict a catastrophic operational-level defeat on Russia, or to destroy the Russian economy. Ukraine’s strategy is to concentrate on the latter, and so it aims to ‘hold’ Russia’s advance on the battlefield while its drones, missiles and diplomats attack Russia’s economy. This choice of strategy probably reflects Ukraine’s lack of manpower, and that is does not have the reserves to risk trying to inflict a catastrophic defeat on Russia. Instead, it uses the advantages of defence to slow Russia’s advance and inflict attrition. Every destroyed tank, armoured vehicle, soldier or mule needs to be replaced to maintain momentum, and each asset costs money to replace.

It is noteworthy that the European intelligence chiefs quoted by Reuters had different assessments of Russian economic capacity, one stating that Russia’s economy is “not on the verge of collapse,’’ while another discussed the potential for Russia to face very high economic risks in 2026.

However, in my opinion Russia’s eventual defeat is inevitable because its economic and military losses are not sustainable in the long-term. Notably, the Atlantic Council reports “Russian casualties have recently reached record highs of more than 30,000 per month. For the first time in the war, this means Russia’s losses are now higher than monthly recruitment levels.” Federov has stated that Ukraine’s aim is to inflict 50,000 casualties per month. A casualty rate that would attrit Russian forces by approx. 20-25,000 soldiers per month.

Additionally, Ukrainians are clearly committed to resisting Russia and are building a world class defence and tech sector to protect their nation. The big question is how quickly can defeat be imposed upon Russia, and unfortunately the answer lies with the Trump administration. A regime that does not appear to value Europe, or Ukraine. Europe on the other hand, understands the threat and continues to support Ukraine. The length of the war will be determined by how quickly Europe can generate the support that Ukraine needs to catastrophically defeat Russia, or crash its economy.

How Russian communications problems are shaping the land campaign

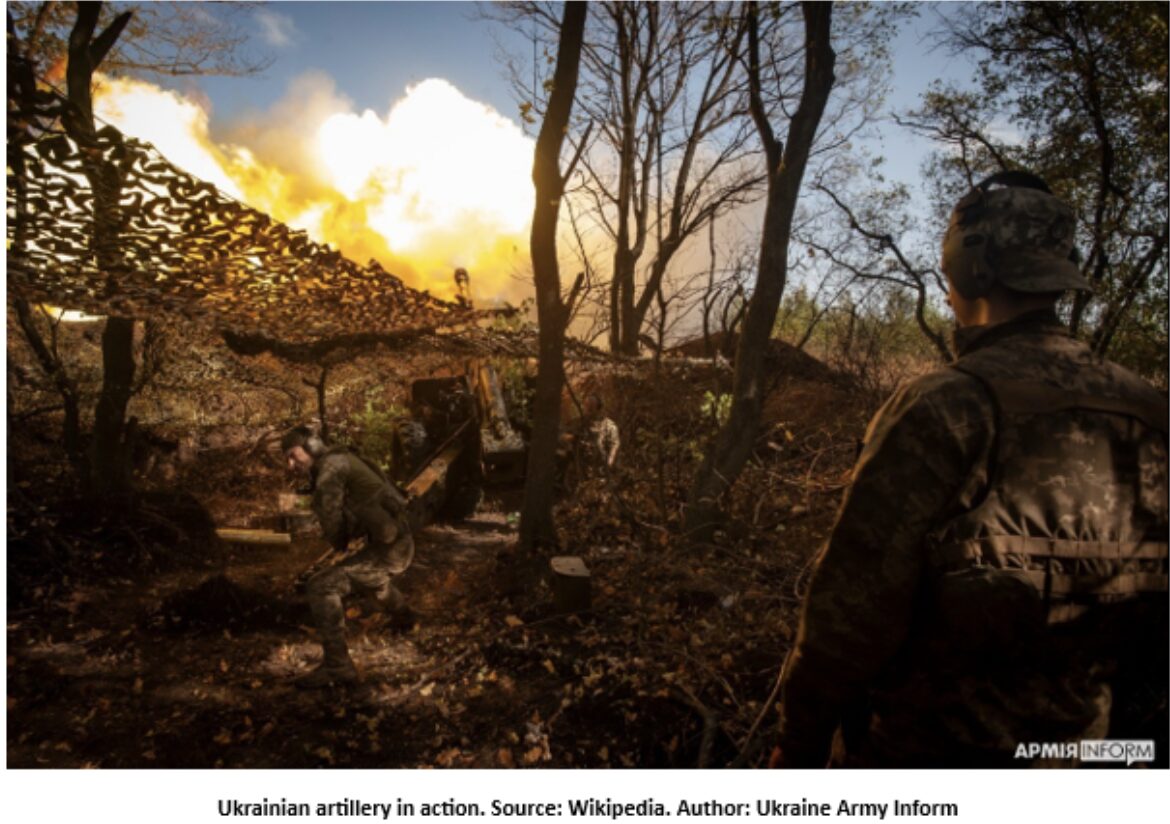

In my previous post about Ukraine, I discussed Russia’s loss of Starlink service in Ukraine. Like Ukraine, Russia relies on digital communications to support its ‘kill web’ of drones, missiles and artillery. Digital communications allow immediate transfer of large quantities of information between the web’s ‘sensors’ that spot targets, and its ‘shooters’ that attack targets.

The lethality of modern militaries is based on their ability to transmit huge quantities of digital data carrying information between ‘sensors’ and ‘shooters.’ Starlink is an effective way to transmit large quantities of data and is not compromised by ‘line of sight’ concerns. A Starlink terminal transmits upwards to the satellite network so unlike terrestrial links is less likely to be blocked by undulating ground, trees or buildings.

Russia has downplayed the loss of Starlink claiming it has viable alternatives, Gazprom Space’s constellation of satellites is probably the most likely option. However, this network of six older telecommunications satellites will struggle to compete with Starlink’s web of approx. 9000 small satellites. Since 2024, China has been building a satellite network to compete with Starlink, Space Sail. This network may be another option but will require time to engineer and its reliability is not as well-tested as Starlink.

Some militaries use modems on vehicles, aircraft or even drones to create local ‘mesh networks’ through which data can be shared within a formation. Russia probably has this capability but it is unlikely that Russian tech competency extends to creating mesh networks that can rival Starlink. The impact of losing Starlink on operations was noted by Euro News that reports since the loss “…Russian troops and the Kremlin-affiliated milbloggers complained about communications and command and control issues on the battlefield.”

Russia’s second communications problem was created by its decision to ban the use of Telegram. A feature of the Ukraine War has been the use of well-tested and reliable civilian communications platforms by frontline forces. Russian tactical communications rely extensively on access to Telegram, soldiers using the coms tech they are familiar with rather than harder to use (and perhaps less reliable) military hardware.

Ukraine’s operational-level plan

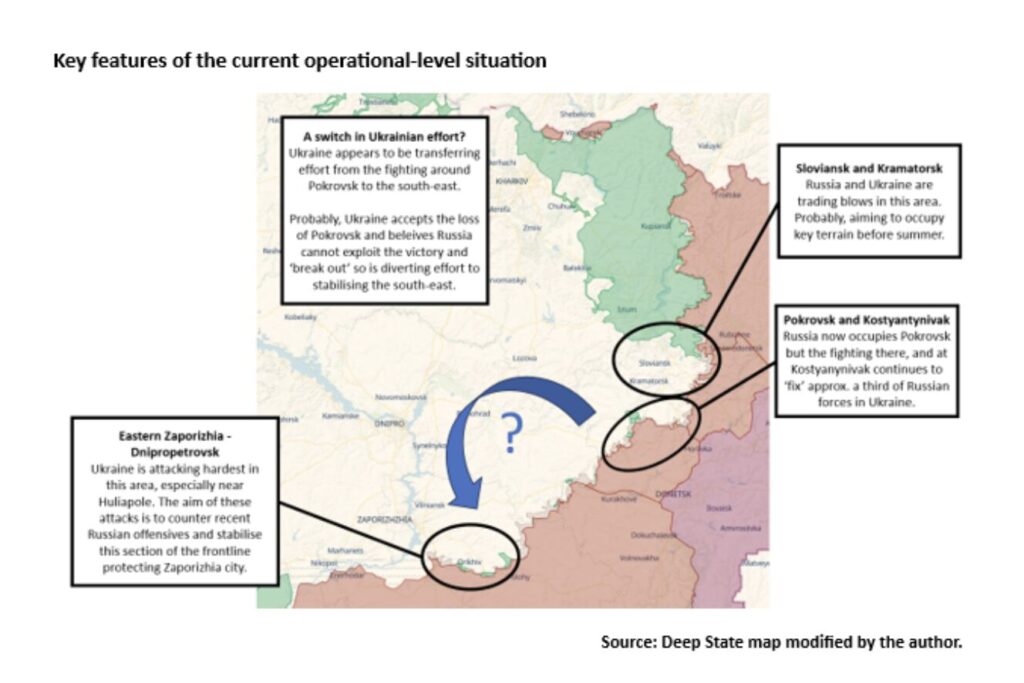

Almost immediately after Starlink and Telegram services were removed; Ukraine started a series of local offensives along the frontline. Generally, these operations appear to be aimed at stabilising the frontline, or at pro-actively denying Russian forces key terrain that could be used to support attacks in the summer.

Ukraine’s main effort appears to be focussed in the south-west near Zaporizhia and Dnipropetrovsk. This area is very flat producing a large ‘grey zone’ of activity in which both sides infiltrate, raid and occasionally capture small settlements. Recently, Russian forces occupied Huliapole a small town approx. 80km south of Zaporizhia city and Ukrainian activity is especially intense in this area.

Further north, Pokrovsk is now occupied by Russian forces and they are closing in on Myrnohrad. The capture of Pokrovsk’s urban area has not stopped the fighting in this area and further north Russia remains heavily engaged near Kostyantynivka.

Pokrovsk’s urban area may be occupied by Russian forces but the surrounding area is not secure. It is likely that Ukrainian drones operating over the farmland that surrounds Pokrovsk will prevent exploitation of the town’s capture by Russian forces. Notably, summer is approaching so bad weather and fog is less likely meaning Ukraine’s drones will be more effective. Further, it will be hard for Russia to advance north from the Pokrovsk area towards Kostyantynivka until Myrnohrad is captured. Therefore, do not expect the capture of Pokrovsk to be significant and either tactical or operational-level.

Ukraine’s gains in the south-west are relatively small, approx. 300 square kilometres according to a recent statement by Ukraine’s president. At this stage, the operation is probably aimed at taking advantage of Russia’s communications trouble to re-shuffle the frontline and strengthen defences before summer. My assessment is that Ukraine is using Pokrovsk, Myrnohrad and Kostyantynivka to ‘fix’ Russian forces in place so they can divert resource to strengthen other parts of the frontline.

Conclusion

Russia now holds the burnt out remains of Pokrovsk. Another Pyrrhic victory, won too late, that does little to influence the wider campaign. Pokrovsk is no longer a useful transport hub its road and rail networks damaged by the battle. But its position on a ridgeline does make it useful for an advance north towards Kostyantynivka, an entry point into Ukraine’s ‘Fortress Belt.’ But, Myrnohrad must be captured before this manoeuvre is possible, reinforcing the conclusion that we should not expect rapid changes in Donetsk.

Instead, we should watch Zaporizhia and Dnipropetrovsk where Ukraine is manoeuvring, and Russia is playing ‘catch up.’ Although it is unlikely – there is a possibility that Ukraine may achieve greater success in this area. Ukraine’s manoeuvre is also important because like the Kherson, Kharkiv and Kursk offensives it demonstrates that Ukraine can take the initiative and is certainly not defeated.

At this point Ukraine continues to stick to its attritional strategy. It is shoring up and reinforcing its defences in the south-west, confident that Russia cannot exploit the capture of Pokrovsk.

I do not expect to see a large Ukrainian offensive because Ukraine is focussed on attrition. Its aim is to drive Russian casualty rates high enough to force negotiation. And, attrition is the cold calculus that will decide this war.

Ben Morgan is a defence and security analyst specialising in modern warfare, military adaptation, and operational-level conflict analysis. He writes on Substack.