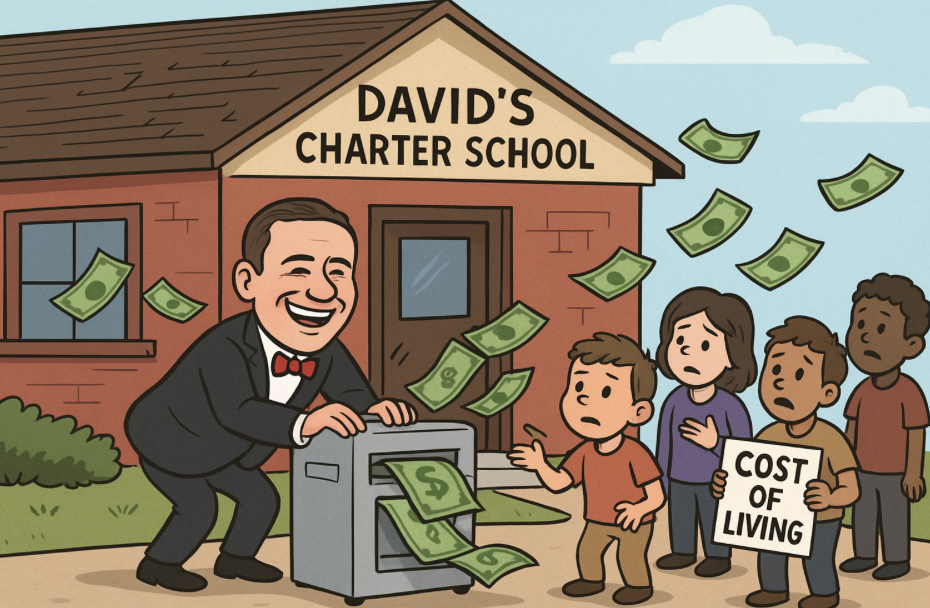

Seymour’s charter school boondoggle continues

David Seymour continues with his agenda to convert New Zealand schools to the charter school model. This is either with the full approval of the National Party, or as was the case with the Regulatory Standards Bill, this was agreed as part of the coalition ‘negotiations’ (otherwise known as Seymour saying ‘jump’ and Luxon saying ‘how high?’)

Recent information from the Charter School Agency is rather revealing:

Charter School Agency reveals enrolment numbers after telling schools to keep figures under wraps

“The Charter School Agency has revealed there are 427 students enrolled in the eight charter schools.”

I’m not surprised the Agency tried to keep this information under wraps. That’s an average of about 53 children per school. Not exactly an overwhelming rush to establish or enrol in charter schools, is it?

The financial situation is equally eyebrow raising:

“Agency staff told the committee the schools’ sponsors received $10.9 million in 2024/25 including $6.3m in one-off establishment funding, and $4.6m in operational funding.

It said much of the operational funding was based on the schools’ “establishment roll”, which was the number of students they expected to have after five school terms of operation.”

Let’s do Erica Stanford basic mathematics: $10.9 million divided by 427 students comes to about $25,000 per student! Note that this is when schools reach their projected establishment roll after five terms, so the actual current rate per existing student would actually be higher. I’m sure every state school in the country would love to have their school funding based on even a fraction of that, say 50%, which would still be way more than they presently receive.

Equity? What’s that?

Naturally, given Seymour’s rhetoric about the benefit of charter schools, we can expect to see miraculous education achievement.

“She said information about students’ achievement and attendance would be published in May next year.

“We have collected interim data and what we can see from that interim data is that most students have made sufficient rates of progress and in some cases accelerated rates of progress,” Lee said.”

What counts as sufficient and accelerated rates of progress? Without further information, that statement has no meaning.

Further, as with Stanford’s sleight of hand over the supposed improvements in mathematics, all this really shows is what could be done if all schools were funded that well, and with the much more favourable teacher/student ratios that would result.

Trying to compare any results from charter schools, with those of state schools, is not comparing like with like, and so there’s little validity. It most definitely can’t be seen as proof of the success of the charter school concept.

Looking overseas, the model that is most frequently used to advertise the ‘success’ of the charter school model is found in the city of New Orleans. After the disastrous Hurricane Katrina in 2005, city authorities made the decision to forcibly convert all schools to charter schools, dismissing teachers and replacing them with Teach for America graduates ( recipients of a roughly two month training programme) and who were then sent into schools to teach.

By 2014 all New Orlean schools are charter schools, and, much like is starting to happen here, the proponents of these schools have been making claims about the success of these schools in raising achievement.

As you’d expect, there’s an underlying story that they are not talking about.

The ‘Miracle’ of New Orleans School Reform Since Katrina Is Not What It Seems

“The city’s all-charter school experiment is a cautionary tale about what happens when democracy is stripped from public education.”

There is one warning that we need to heed.

Here’s another one:

“The Gates, Broad, Walton, Fischer, and Bloomberg foundations, already enamoured with charter schools, collectively invested an estimated $77 million along with other donors in rebuilding New Orleans’s schools between 2006 and 2013.”

What attracted these foundations? Making a profit seems to be a plausible reason. What is attracting New Zealand organisations to invest in charter schools? Same reason?

The proponents of the New Orleans charter schools have claimed that educational results prove the charter school concept.

However:

“The closing of “failing” charter schools, a feature of the city’s model, is cited by REACH as the primary driver of test score increases between 2008 and 2014. According to data derived from the Common Core of Data (a database of the National Center for Education Statistics), of the 125 charter schools that opened in New Orleans since Katrina, sixty-one have closed, and others were taken over by different charter management organisations. Among the sixty-one schools that closed, the average lifespan was only six and a half years. Although some schools were closed due to low test scores, others were closed because of low enrolment and financial mismanagement, and still others closed amid scandal.”

There is nothing to stop the same happening with the charter school model here, and if my memory is correct, some charter schools did suddenly shut up shop during Seymour’s last attempt to introduce them in the 2009 – 2017 period, when he called them ‘partnership schools.’

No consideration seems to have been given to the disruption to children’s education caused by frequent and unexpected school closures. It’s well established that moving schools in New Zealand sets back a child’s learning by up to a term.

As for the closure of schools being seen as a driver of success in New Orleans:

“Scholar Bruce Baker argued that a “significant reduction in concentrated poverty,” along with a dramatic increase in spending, were in fact the drivers of test score improvement.”

Two issues here that are applicable to New Zealand, one being the proven factor that socio-economic factors are the biggest influence on children’s learning – something recognised by the first Labour government which believed that children needed to the well housed, well fed, well clothed, and with free access to medical services, in order to be able to learn at school.

The second issue is the one I raised above – the need for all schools to be adequately funded and staffed in order to be able to provide the best possible learning experiences for children. Neither of these apply to New Zealand schools.

Get the socio-economics sorted and fund schools properly, and we don’t need to import fanciful concepts such as the knowledge rich curriculum.

“A 2015 study by the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE) concluded that the “constantly changing metrics,” which included “changes in both [test standards] and content,” resulted in different conclusions regarding the efficacy of reform.”

This has the same flavour as Stanford’s very selective use of dubious test results to prove the success of her curriculum developments.

“Noting that New Orleans was “one of the lowest-performing districts in one of the lowest-performing states in the United States,” the SCOPE study also concluded that New Orleans-style school reform, as it exists now, is not a model that should be replicated.”

Which immediately begs the question, why is Seymour so hell-bent on doing the same to New Zealand schooling?

“The truth is that the all-charter experiment in New Orleans was built on the displacement of Black educators, the silencing of parents, and the infusion of foundation dollars with strings attached. As a result, students and families have faced disruption, instability, and hardship as charter schools open and close. Two decades later, the “miracle” is not what it seems. It is instead a cautionary tale about what happens when democracy is stripped from public education and governance is handed over to markets and philanthropies”.

There’s that warning again.

The concluding paragraph sends us another warning:

“Meanwhile, parents like Bigard, whose children bear the brunt of an experiment they did not ask for, can only dream of what might have been if resources, guidance, and community voices had been a part of rebuilding the city’s schools. The very same achievement results, or better, may have occurred with far less chaos and pain.”

To conclude, here is a selection of quotes taken from the following article.

Whose Choice? Student Experiences and Outcomes in the New Orleans School Marketplace

So what’s the rationale used in the USA for charter schools?

“The charter movement has been inspired by several rationales, among them the idea that better educational outcomes will result if

- families can choose schools with different philosophies and programs that fit their preferences and needs;

- school providers are given opportunities to innovate unconstrained by bureaucratic requirements regarding their design, staffing, and operations; and

- schools are motivated to improve through competition for customers (who bring with them enrolment dollars) and through the requirement that they will be evaluated and reapproved for operation every few years.”

Does this sound familiar to you? It should, as this is pretty much the ideology that Seymour expresses.

The next section discusses difficulties many children have in enrolling in schools of their choice.

“Zimmerman conducted a geographic analysis of public school enrollment in New Orleans and found that despite the city’s far-reaching school choice policy, low-income minorities have significantly limited access to quality schools. This finding was confirmed by the respondents’ experiences in this study. In many instances, parents spoke about choosing between the schools that were left to them or choosing schools that their child was likely to get into. Students talked about not getting their choice or having to go to a school that had an opening versus being able to truly decide on a school that they wanted.”

This especially affects children with special needs:

“Many of the concerns were accounts of school staff members who sought to dissuade parents from enrolling because the school didn’t have the appropriate staff, such as para-educators or one-on-one aides; proper building capabilities, like an elevator or ramps; or because the school’s plan for special education instruction consisted of inclusion only, viewed as inappropriate for students with severe disabilities such as mental retardation.

According to one special education expert, this resulted in special needs students “scrambling for limited places.” In some instances, parents reported attempting to apply to 20 or 30 different schools, hoping to get a seat.”

And:

“Full inclusion here doesn’t mean any level of support for kids. That’s the problem. That’s what we’ve said all along to them. Yes we do want full inclusion, but that doesn’t mean you just throw a kid into a classroom and think that everything is going to be fine. And that’s essentially what they’ve done. So full inclusion is a joke…that’s problematic going forward because it sets kids up for failure.”

Many New Zealand parents of children with special needs struggle to find a school as it is, so just imagine how it could be if charter schools became predominant type of school across the country? And to be fair, due to lack of resourcing and staffing, currently many/most schools find it very difficult to provide quality education for children with special needs, in spite of their best intentions.

Here is another warning:

“In a system that has no system, the key word to describe educational practice is variability. Curricular approaches and educational program offerings vary substantially from school to school, as do teaching strategies and disciplinary practices. Whereas districts that have undertaken research-based instructional reforms offer similar learning opportunities to students and are developing similar practices among educators,34 in New Orleans each school or network of charter schools functions independently. Each school can develop its own philosophy and practices with little to no support, guidance, or oversight from a central office.

The virtue of this brave new world is the freedom for schools to experiment with a range of methods. At the same time, without common standards or a system of oversight, experimentation is not necessarily always guided by knowledge of best practices or by a common set of educational or ethical principles. The system also provides no guarantee that minimum standards for educational opportunity are being met.”

Indeed.

Thee quotes I’ve used are but a very brief snapshot of these very comprehensive publications, much of which lie way outside the scope of this article.

However the overriding thing which stands out, is that going down the charter school road is one fraught with warnings. I can’t see much that is good coming out of Seymour’s agenda to convert New Zealand schooling to a charter school based model.

When I look at the share of the vote that ACT got last election, I have to ask the question, yet again – why did Seymour get so much power and influence over the policies of this government?

Allan Alach is TDBs Education Blogger

Latest on Scoop and the NZ Principals on studies from the UK showing suggested ed ideas by Heretical don’t/won’t work.

https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/ED2512/S00004/curriculum-changes-ignore-crucial-evidence-from-englands-education-review.htm Dec 2/25

…”The Minister of Education claims she is focused on closing the gap between our highest and lowest performing students, yet the Government is implementing an education framework that will almost certainly make things worse,” says New Zealand Principals’ Federation President Leanne Otene.

“The evidence clearly shows that a knowledge-based curriculum fails to deliver the improvements in educational equity it claims to promote. It ignores the fact that students are individuals, many with diverse needs that require different education strategies to succeed…

I think it has been said before but the government doesn’t have to listen to any seasoned advice only that which will lead them to bags of gold, overseas trips, and inflated egos which never seem to burst, made of rawhide I think.

And for simple minds like mine the mention of something makes me go off like a politician.

The Blues Brothers with Rawhide which might give you a wry laugh – Kiwis would never get that enthusiastic. They’d stay wild and destructive, moan and point finger.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdR6MN2jKYs

Well, there we go. Proof yet again that the whole dodgy scheme is not going to work.

Luckily only 427 families have been silly enough to get involved with a charter school. Did that compel Seymour to try to force KBHS to become a charter school? He picked a poorer area with busy, struggling parents and hoped they wouldn’t fight back.

With $25,000 being spent on each of those 427 students, there should be absolutely no failures. You don’t get to spend that kind of money per person and have them achieve a ‘sufficient’ grade. You expect significantly improved results.

This man has far too much say in our govt. His share of the electorate does not warrant such power.

Time for a new really important Bill to be introduced!!! AA your last paragraph says it all. No party, as part of a coalition, should EVER be able to force onto the voting public, their narrow, one-sided views, with less than 50% of the major party’s original vote AND what’s more, the voting public need to be told ALL the details of the amalgamation promises. We need to stop this electoral vandalism so someone has to sort this! Otherwise, NO MORE COALITIONS! Seymour is OUT OF CONTROL; STUFFED UP with his own SELF-IMPORTANCE and BEHOLDEN to Atlas! He’s akin to a unhealthy, sick virus that needs to be exterminated. Again, and again, what in the hell did we do to deserve this egotistical maniac? So sick of it all! He doesn’t give a hoot about NZ or its people. Please make him go away for good!

The problem with your idea about minor parties not being allowed to force narrow one sided views is that, while it seems like a great idea, how would you feel when its the Maori party or the greens doing it? This is what Americans don’t realize about trumps executive orders. Now that he is protected from prosecution no matter what he does as pres, the same will apply when its a democratic pres. That is why you need to be very careful about changing or imposing those types of rules.

They reason why Sleezemore got a lot out of this Coc agreement even though he got a small amount of votes comparative to the larger party IMO because his partners believed that he has the ability to BS effortlessly with rhetorical ease coupled with seemingly sounding coherent that makes his argument more plausible and that he had familiarity with the minute details of charter schools