Recycling has always been a scam

Officials want to ensure recycling sent overseas is reused

Government departments have proposed a plan to ensure the thousands of tonnes of recycling sent overseas every year is actually being recycled — but have rejected a plea for a total ban on exports.

That’s disappointed Auckland lawyer Lydia Chai whose petition to halt plastic exports to developing countries drew more than 11,000 signatures.

“It is unethical for us to be relying on poorer countries, with not very good democratic systems, to be processing our waste,” she said.

In a response to her petition at select committee in June 2023, a senior official admitted: “We don’t know how much of this stuff being dumped and how much of it is being reused”.

That was because currently there was very little regulation of the industry. It was estimated about a quarter of New Zealand’s recycling was exported — equating to around 22,000 tones of plastic in 2022, with most going to Malaysia and Indonesia.

We aren’t recycling that plastic, it’s being buried in poor peoples country’s!

Recycling has always been a scam…

Auckland Council contractor accused of mixing rubbish and recycling in one truck

A central Auckland business owner claims he saw a council contractor throwinglandfill and recycling into the same rubbish truck.

It has sparked accusations of hypocrisy as Auckland Council has threatened to removed recycling bins from residents who are not following the rules.

The council’s general manager of waste solutions, Parul Sood, said the organisation was “very concerned” to hear the man’s claim but could not confirm the incident. She said any contamination of recycling was unacceptable.

…One of the most important myths spread by Climate Deniers and their corporate enablers is the lie that collective lifestyle changes by individuals can stop climate change.

Bullshit.

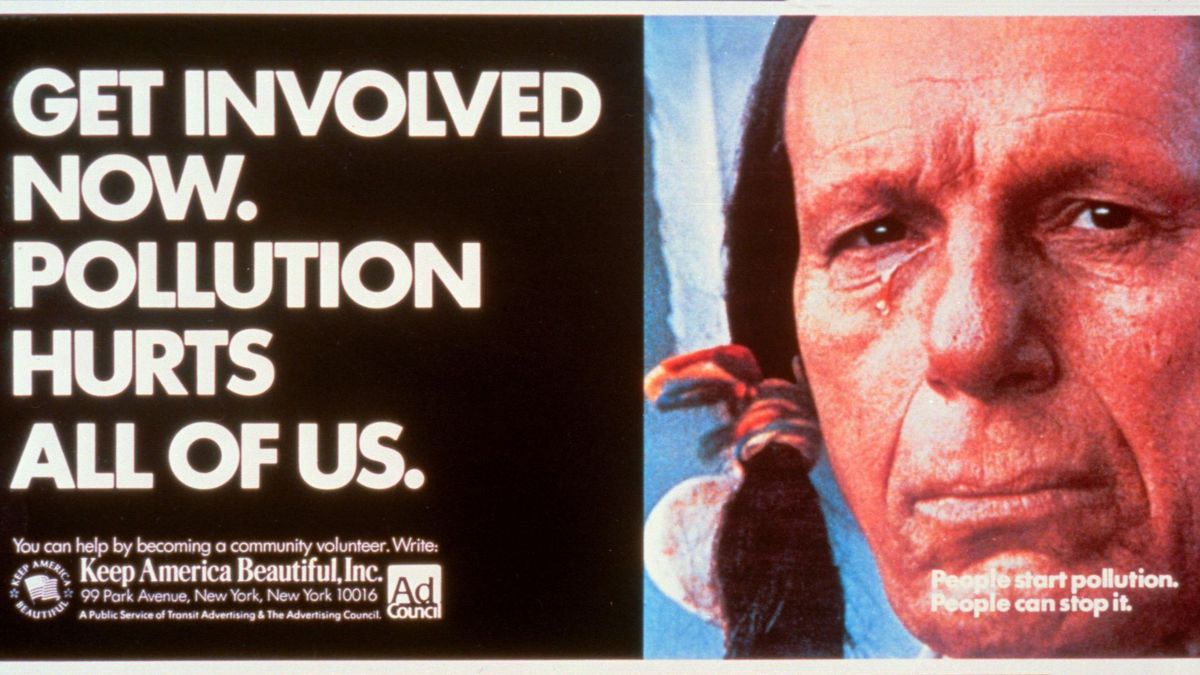

It’s the grand Keep America Beautiful scam. That 1970s campaign used the tears of a native American Indian crying at all the littering to hammer home the message that pollution and littering was an individual responsibility, certainly not something that required legislation.

This lie, that individual action can change the environment is an important fiction to progressives who want to give activists something positive to hope for but most importantly this lie allows the polluters off the hook!

You cycling, not eating meat, recycling and catching a bus won’t change the horror apocalypse in front of us, because the real issue are the mega corporations who are benefitting from our consumer culture addiction!

Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says

Just 100 companies have been the source of more than 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions since 1988, according to a new report.

The Carbon Majors Report (pdf) “pinpoints how a relatively small set of fossil fuel producers may hold the key to systemic change on carbon emissions,” says Pedro Faria, technical director at environmental non-profit CDP, which published the report in collaboration with the Climate Accountability Institute.

The report found that 25 corporate and state producing entities account for 51% of global industrial [greenhouse gas] emissions and all 100 [fossil fuel] producers account for 71% of global industrial [greenhouse gas] emissions.

It’s not about you becoming a flexitarian and championing bike lanes FFS, it’s about mega corporations being allowed to profit from the end of the world!

Blaming consumers who have been addicted to this cheap dirty energy and not the dealers for building the infrastructure to exploit that addiction is a clever distraction from demanding radical reform of those mega corporations.

Look, sure, get a bike, catch public transport, recycle and eat less meat. Think of them as weekly prayers and rituals to post growth our lives and culture, go for it.

But don’t pretend those rituals and prayers will significantly postpone the climate crisis tipping points and catastrophic events if the mega corporations are not curtailed.

Thankfully that’s what Mike Smith is doing!

We need to be kinder to individuals and crueller to corporations.

I just want to sound a note of caution about throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

Yes, recycling a thing is no substitute for not making it in the first place if it’s avoidable (yes, I’m looking at you disposable plastic bags). Yes, making products genuinely multi-use or compostable is better than trying to recycle huge volumes of disposable stuff. Yes, the recycling systems we have, although they’ve come a long way, are still flawed and inadequate. As anyone who’s genuinely tried to hold zerowaste events can tell you.

But the *concept* of recycling; reclaiming materials from end-of-life products to make new ones, instead of burying or burning them? That’s most definitely *not* a scam. If we are to continue manufacturing things that can’t be safely eaten or composted, we must have functional systems for reclaiming the materials in those products when they can no longer be repaired or repurposed.

Where I agree with Bomber (and others like Adam Ruins Everything who’ve covered this topic) is that the responsibility for ecologically wise disposal should *not* lie with the people who end up with products at their end-of-life. People who are likely to be low income, and therefore buying lower quality products, or repairing and repurposing things cast off by wealthier people who can afford to buy new ones instead. Neither should that cost fall on local councils, as much of it does right now.

The people who ran the E-Day to collect e-waste in Aotearoa from 2007-2010 proposed a “product stewardship” model (https://eday.org.nz/what-is-ewaste/how-to-solve-the-ewaste-crisis.html). Where the price of recycling electronic products is paid by its manufacturers and retailers, who may or may not be able to pass it on to the first owner as part of the purchase price. To do that, we could charge a levy on any product when it comes into the country (or is bought from the manufacturer if made here) and use that to fund the costs of recycling that product effectively. Or we could oblige retailers to accept returns of product they sell when they’re no longer useful, so they have to organise and pay for recycling them

I agree with this, and I see no reason why it applies only to electronics. Would the Warehouse and all those $2 shops be full of designer landfill if the people selling it had to add the full cost of end-of-life disposal to the purchase price (‘internalise’ it), or absorb it themselves? Maybe goods designed to be more durable, or easier to repair and recycle, could end up being more profitable, and we’d have a whole lot less waste to recycle, bury, or burn.

All the council’s are Green Washing then.

Recycling wasn’t a scam when glass bottles were simply washed and refilled.

But that’s bad for brand differentiation, so how could the government simply… enforce a standard? It seems to work out just fine for the monopsony that is the production of crate beer in this country, obviously they are doing well off being able to get their customers to give them containers back. But I guess milk is ‘special’ somehow.

Mohammed Khan Glass bottles, yes. Milk was in glass bottles too, with empties left out for the daily milkman. Jam was in glass jars, salvageable for various household use. Sugar came in hessian-type bags and flour in cotton flour bags, all recycled to make the oven cloths, aprons etc which were popular fundraisers at a school and church fairs, and unnecessary plastic packaging simply didn’t exist.

Much of my recycling is various unnecessary, unhealthy, and unwelcome plastic food wrappings. Newspapers were made into fire logs or otherwise used eg for window cleaning, or weed -killing mats, kids’ kites, or wrapped around the chests of poor people without adequate clothing to keep out winter’s cold, although, ironically, clothing was formerly much better quality too, not el cheapo imported crap made to last one season. Our own woollen mills provided the materials for innovative European immigrants to produce the high quality garments which lasted for decades and were passed down through families.

Too true. Nowadays most of the actual recycling I am able to do in this society is cutting up worn out clothes to use as cleaning rags. I suppose I could donate them to the sallies to be cut up for use as shop rags by mechanics, which is laudable enough, but why not bypass the middleman?

I don’t think it would be unfair to suggest that about 50% of the population has an incorrect understanding of what to put in the recycling bin so the scheme is flawed from the start. As you say the companies that benefit from that ignorance should pay the cost instead of leaving taxpayers with the results of their pollution. Human nature being what it is you are never going to get enough people choosing to do what is best for them as we have various desires that take precedence over actual evidence which is why I put my trust in a higher power.

Agreed rycycling scam.. in my prov town during Covid the recyc truck went from 2 drivers to 1..ie the streetside sorting didn’t happen … post covid it stayed like that.. my old neighbour was on to it “not sorted curbside= sure AF not sorted at the depot (manually at mega scale) = all going to landfill” yet it’s still a separate truck :). The good news is Dharleen Tana is working hard overtime on it as this is her portfolio!!!