Waatea News Column: Māori Party GST off food vs sugary drinks

Jack Tame on Q+A yesterday pushed Māori Party co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer on how the Māori Party GST off food would work.

He asked would GST come off Coke, the insinuation being that a policy driven to lower the price of food would also end up allowing unhealthy choices to be cheaper.

Debbie Ngarewa-Packer countered that the Māori Party didn’t want to food shame or judge hungry people, which is a righteous position to take, but the question remains, how will a problem like fizzy sugary drinks be fixed because this isn’t about food shaming, it is about stopping Big Sugar being able to sell their addictive product directly to hungry people.

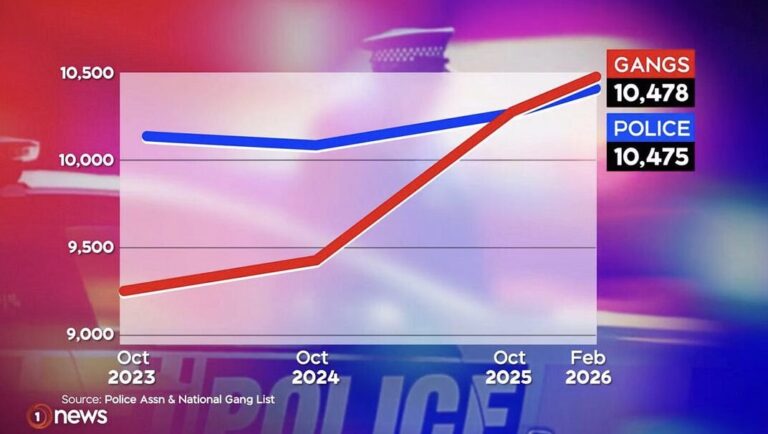

Food inflation hit 12% last month, and global geopolitical tensions alongside cyclone damage to our agricultural cycle will see that inflation push even higher.

Taking GST off food is one way to tackle that cost of living crisis directly.

One way the Māori Party could bypass making unhealthy sugary drinks cheaper by removing 15% GST would be to slap a 15% sugary tax on right after taking the GST off!

That way the price of a sugary fizzy drink would stay the same for consumers, (so as to not punish or incentivise consumption) WHILE taxing sugary drinks to pay for free dental.

Because the Māori Party are focused on solutions, they are open to new ideas that can generate multiple benefits.

Removing 15% GST off food and then slapping a 15% tax on sugary drinks is a solution.

First published on Waatea News.

There are some cheap sugary drinks in New Zealand but most sugary drinks are now more expensive due to inflation. The goal would be to reduce the amount of GST.

Personally I feel that a rate of 12.5 percent is, and was, better compared to the current rate of GST, of 15 percent.

Well New Zealand taxes alcohol heavily, in part because of the social damage it causes, and taxes tobacco heavily for the same reason.

Given the social harm that sugar causes, surely it’s a no-brainer. . .

The first question that I have is, will this be exempting food from GST or zero-rating it? You may ask, what is the difference? The answer is a fair bit.

If food becomes an exempt supply throughout the supply chain, the likely reduction in price to the end consumer will be minimal; being the GST portion of the vendor’s gross profit margin. This is because the businesses along the supply chain will not be able to claim the GST they incur in respect of food. Such costs include growing food, transporting food, and apportionments of input claims on rent, power, marketing, and other costs.

If food is a zero-rated supply when sold to the end consumer the reduction in price should equal to, or at least approach, the “tax fraction,” i.e., 3/23rds of the price with GST at 15%.

Why 3/23rds and not 15%? The GST inclusive price of a good (taking the current rate of 15%) is 15/100+15, which simplifies to 3/23rds. The level of price reduction depends on whether vendors pass on the full 3/23rds.

I suspect that advocates of removing GST from food envisage zero-rating as this will achieve a greater price reduction than treating food as an exempt supply.

The second question is what foods will be zero-rated? Fresh food? Healthy food? All food except takeaways and snacks? All food? This may well come down to policy decisions to promote healthy food at the expense of high fat and/or high sugar foods.

In Australia, GST applies to food and beverages consumed on the vendor’s premises, and to hot food supplied as take-aways. All other food is “GST-free;” zero-rated in the terminology of our GST legislation.

In Canada supermarket checkouts have thermometers to determine the temperature of cooked chicken at the time of sale. Canadian GST has different rates for food and take-aways; chicken above a set temperature is a take-away, subject to a higher rate of GST.

Even the goal of exempting basic food items can create issues. Bread is a basic food item, but what about bread served as a separate item at a restaurant? What about a meal served on a long-distance train trip? And would there be different GST consequences if the meal were included in the cost of the ticket?

The above examples are no meant to trivialise, rather to illustrate

Some of those who reject the calls for removing GST from food generally argue that:

• New Zealand’s GST is the best value added tax system in the world because it has only one standard tax rate and very few exceptions.

• Policy makers decided that the administrative and compliance costs of having selected goods and services exempt from GST would be too high.

• Levying GST on as wide a range of goods and services as possible is that the wider the tax base, the lower rate of tax required for any given amount of tax revenue.

• Removing GST creates higher costs in the long-run due to a less efficient tax system as additional administration is required and greater compliance costs are incurred.

There have been many changes to the GST legislation since it was first passed in 1985. Tax systems and tax legislation both continue to evolve. I believe that two rates of GST, with a lower rate for food, could be incorporated into the legislation. Alternatively, food could be zero-rated.

A few critics argue that the standard rate of GST would have to increase if food was zero-rated or subject to a lower rate of GST. This assumes that the same amount of GST would need to be generated. This represents, the third question – how is the reduction in GST gathered replaced?

If food is zero-rated, or subject to a lower rate of tax, the GST shortfall could be generated by a combination of some or all of the following:

• Reducing the tax gap – stamping down on tax evasion and tax avoidance. Compliance could be encouraged by higher penalties;

• Introducing new taxes – a comprehensive capital gains tax, a wealth tax, or a financial transactions tax, or possibly a combination of two or more new taxes;

• Reintroducing old taxes on wealth transfers – Gift and Estate Duties; or

• Ensuring that multinational companies pay a higher effective rate of income tax in New Zealand. Note, I resisted using the term “fair rate of tax.” Is it realistic to accept an increase in tax paid by multinationals, as the political and economic cost of ensuring that the payment of a higher effective rate of tax may well outweigh the marginal tax benefit.

The further reform of the tax system is a subject for a future blog post.

GST has an important role in our tax system. That does not mean that I agree with a 15% tax rate on virtually all goods and services. I believe that, ideally, the rate should be 10%, or we have two rates, a standard rate of 15% and a lower rate for food of 5% or 7.5%.

Based on the inflation impact of the introduction of and subsequent increases in GST, a reduction in GST to 10% could result in a reduction in inflation of up to 3.25%. This depends on vendors passing on the full reduction in GST.

The overall tax system needs reform to achieve greater equity. I acknowledge, however, that it is politically easier to tinker with an existing tax than introduce a new tax. Our government needs the courage to match its purported convictions and introduce a wider range of taxes and reduce the rate of GST.

We know that things have gone made when Pak n Save have 200ml of energy drinks for 99c on special yet half a cauliflower is $5

GST off food is a silly policy which would not help much in the long run. A sugar tax would be a great idea but with the connection of this government to the drinks industry I doubt if it will see the light of day.The Maori Party would not bring it in as they would say it would effect Maori more than most and they should not be picked on . In the UK the tax has worked well with the average sugar content falling by nearly a half .The industry fought it hard but that has stopped largely due to fact the sales of soft drinks has increased not fallen .The tax money gained was aim at obesity problems so a win win

Trevor, you seem to think that lobby groups only pertain to Labour. It’s been going on for years, it’s just that now the right wing media want to make the most out of it in election year. The alcohol industry and trucking industry have been the biggest lobbyists for the National party for well over 50 years.

I commend TPM for this stance.

They are well ahead of National on policy.

I have no doubt they will be king and queen maker at the election and they will never form a coalition with the corrupt right ever again.