The compulsory te reo problem

Winston Peters tells ministers touting compulsory te reo to get ‘on the same page’

NZ First leader Winston Peters says if Nanaia Mahuta and Willie Jackson want to be in the Government they will need to watch their words.

Māori Development Minister Mahuta said compulsory te reo in schools was a matter of “not if but going to be when” on Tuesday morning.

I think we get tripped up on the word compulsory when it comes to te reo.

There is a body of opinion that argues te reo is an official language and is a cultural taonga and as such we must make the effort to make it compulsory. Sign language is also an offical language and I’m not sure making that compulsory would be justified.

I support public agencies lifting their game and making te reo inclusive but the backlash of making the language compulsory would get ugly and quickly derail the rest of the political agenda. The other problem is that we simply don’t have enough teachers of the Māori language to make it compulsory.

I say this while acknowledging my daughter is in a Māori immersion class and it fills me with immense joy when she speaks the language.

I think an easier way forward than forcing this is encouraging it. The Education Review did a good piece on this last year and their solution looks like the best move…

Big bold steps they may be, but Paora Trim has come up with a simplistic and scalable way that teaching and learning te reo could be achievable in our schools.

Trim’s practical solution is one that his son’s primary school is trialling this year. Each week, teachers will teach their classes two Māori words and one Māori phrase. The following week, they review the previous week’s words and phrase before learning new ones.

“Imagine if a child was taught two words and one phrase of te reo Māori each week from the time they started New Entrants. After 10 years at school they could potentially know 800 words and 400 phrases.”

It would take an estimated five minutes each day to teach two words and one phrase a week.

Trim acknowledges that teachers will have different levels of reo proficiency, but he doesn’t see this as a problem. He points to various apps and online programmes that could be used by anyone.

“They’d learn along the way too,” he says.

The key to the success of a programme like this is getting the buy-in from a school’s senior leadership team. They need to motivate and make staff accountable, says Trim, while the school’s language expert is responsible for providing resources and supporting staff.

…my only concern with the current cultural currency of speaking and pronouncing Māori is that it ends up becoming a new micro-aggression policing aesthetic.

Is it good enough in 2018 to champion Te Reo when the structural injustice of colonialism is so prevalent and apparent?

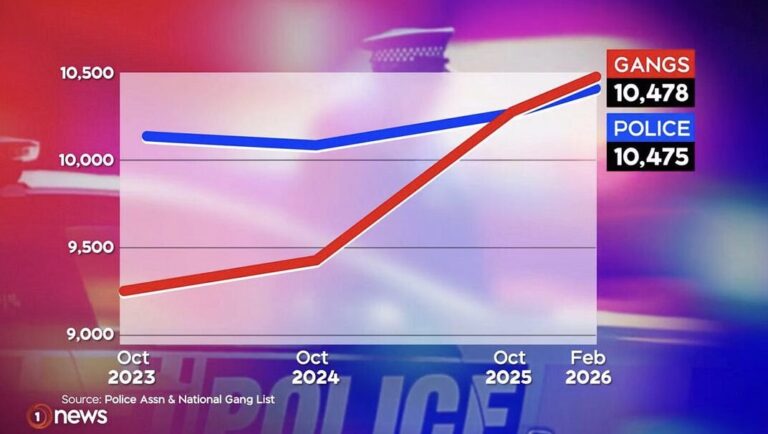

Māori are 380% more likely to be convicted of a crime, 200% more likely to die from heart disease & suicide. Māori are paid 18% less and 34% leave school without a qualification. Māori at 15% of the population make up over 50% of the 10 000 prison population. They are arrested at a higher percentage, feature in the worst education and social stats and make up a huge proportion of those living in poverty.

After losing 95% of their land and economic base in less than a century and overcoming almost being wiped out by disease and muskets, Māori have been cheated by the Treaty.

I believe that the majority of white New Zealanders live in a constant state of wilful ignorance when it comes to racism in this country. The facts of how racist our system really is are glaring in the statistical outcomes, and have come under investigation by the UN.

The NZ Herald’s first editorial ever was calling on white settlers to go to war with Māori and it took 136 years to get an apology for Parihaka, who will apologise for the racist failures of NZ since the Treaty?

Knowing your Te Reo is simply cultural appropriation if it isn’t coupled with the same level of effort in cementing into place the power dynamics laid out in the Treaty.

Getting tangled up in making it compulsory is missing the opportunity to progress while requiring focus on the structural racism that blights NZ.

““Imagine if a child was taught two words and one phrase of te reo Māori each week from the time they started New Entrants. After 10 years at school they could potentially know 800 words and 400 phrases.””

In my view, before such strategies are implemented in schools, there needs to be a clearly-articulated goal. What is the aim of following this path? If the goal is fluency in te reo, by itself it’ll be unsuccessful; the vocabulary acquired would be far too small. In addition, children need much more than just words and phrases, if they are to be competent language speakers.

See this: “By the time a child reaches school age and heads to kindergarten, he/she will have between a 2,100- and 2,200-word vocabulary. The 6-year-old child typically has a 2,600 word expressive vocabulary (words he or she says), and a receptive vocabulary (words he or she understands) of 20,000–24,000 words.” From: https://www.superduperinc.com/handouts/pdf/149_VocabularyDevelopment.pdf

If the goal is to give non-Maori children familiarity with te reo pronunciation, it may well work. But for Maori children, it wouldn’t ensure that they were fluent in their language.

As I understand the current situation, studying English or te reo is compulsory for secondary school pupils; making te reo compulsory in primary schools would require a pool of qualified teachers that doesn’t yet exist. On the other hand, teaching children a couple of words and phrases a week wouldn’t require teachers qualified in te reo, but it wouldn’t confer language fluency, either.

I grew to adulthood in the 1960s; in the 1970s, at a time when there were many native speakers, I learned te reo. I remember the beginning of the kohanga reo movement in the early 1980s; at that time, many people thought that kohanga would save the language. But that appears not to have happened; that’s because, for survival, any language needs native speakers. Teaching preschool children te reo isn’t a substitute for it being the first language they learn, and which they speak pretty much exclusively for the first few years of their lives: preferably till they’re 4 or 5.

It’s difficult to find up-to-date stats on the numbers of native speakers of te reo. Census information suggests that there are very few; possibly none. And this is a perilous situation for the language. It appears that the decline in native speakers has been contemporaneous with the rise of the kohanga reo system. So it wasn’t the saviour of the language, even though that was the intention of the founders.

The survival of languages is critically dependent upon their utility. Te reo will survive if people want to use it. Making it compulsory in the curriculum won’t save it long term, if people don’t use it, or can’t use it, in daily life. The Irish have found this out. And if any country had a head start in saving its language, it is Ireland. But attempting to preserve or resurrect languages for political reasons is generally unsuccessful.

“Māori are 380% more likely to be convicted of a crime, 200% more likely to die from heart disease & suicide. Māori are paid 18% less and 34% leave school without a qualification. Māori at 15% of the population make up over 50% of the 10 000 prison population. They are arrested at a higher percentage, feature in the worst education and social stats and make up a huge proportion of those living in poverty.”

In the 1960s and 70s, Maori didn’t clog up the prisons to anything like the extent that they do now. Nor were they overrepresented in negative education, employment and health stats. Back then, those who were poor, in prison and unemployed were as likely as not to be pakeha. In the mid-60s, there was almost full employment. And back then, there were aspects of our legislative arrangements which indisputably discriminated against Maori.

From the late 1960s, unemployment began to creep up, made worse by the UK entering the European Common Market in 1973 – and throwing us to the economic wolves in the process. It was neoliberalism (Rogernomics) – coupled with the spread of cannabis use – which really destroyed Maori society. And then – in the early noughties, as far as I can recall – it was the arrival of methamphetamine which caused colossal damage.

It’s best not to blame colonialism for the current dire situation of either Maori society, or of te reo. In the first place, it’s clear that more recent political and economic developments have done the damage we now see. And in the second place, no pakeha now alive is responsible for either colonialism, or for the large-scale land confiscations that happened back in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Further, most of us aren’t even the descendants of those responsible for early colonial depredations. Blaming any of it on us is a surefire way to exacerbating any hostility pakeha may feel.

Technically correct, D’Esterre, but I would point out that (a) pakeha alive today have benefitted from those illegal land confiscations and other acts of colonialism and (b) many pakeha alive today actively resist remediation of colonialism and land seizures, to maintain their positions of economic power.

Which, by the way, is precisely what Israel is planning with the colonisation of the West Bank with “settlements”.

Frank: “Technically correct…”

Not technically correct, Frank: factually correct. I don’t deny the terrible economic and psychological damage wrought by colonialism upon earlier generations of Maori. And as we have seen, the psychological effects of colonialism – language and cultural loss, discrimination – persist, often long after the economic effects have been ameliorated by development. Nevertheless, the proximal cause of the current parlous situation of many Maori has been neoliberalism (and the noxious drug epidemic), even if colonialism exerts distal effects.

“pakeha alive today have benefitted from those illegal land confiscations and other acts of colonialism”

Uncomfortable as it may be to accept, at least in economic terms so did those Maori who were employed by, and benefited from, the post-war boom in production that resulted from colonialism. Not all aspects of colonialism were deleterious. At first contact with Europeans, Maori society was pre-literate, with no prior exposure to modern technology. Colonisation brought many material benefits, not least being introduced animals; I remember reading somewhere that these foodstuffs saved Maori from large scale starvation, because existing food sources were by that time rapidly becoming insufficient to feed the population at the size it was then.

“many pakeha alive today actively resist remediation of colonialism and land seizures”

I’m not sure what you mean by this. Are you suggesting that there’s a pakeha group along the lines of the Afrikaaner resistance movement, agitating against Treaty settlements? If so, I’ve seen no evidence of it.

I’m old enough to remember the years of Nga Tamatoa activism: NZ before the Waitangi tribunal was established. Back then, many of us – including Maori – thought that we were headed for bloody revolution, as had happened elsewhere in the world.

Fortunately for all of us, the Waitangi tribunal decisions, along with governments’ acceptance of the need for restitution, took much of the heat out of the situation. As I recall, there was much argument, and many pakeha took a bit of convincing as to the justice of Treaty settlements. But the sky didn’t fall, and people gradually accepted them. Possibly it helped that the first contemporary settlements were under the aegis of a National government.

Of course, that was over 20 years ago, and it was my generation went through all that turmoil. Perhaps the next generation down, who’ve been most indoctrinated with neolib solipsism, are less inclined to see the value in collective justice. I haven’t encountered that in my neck of the woods, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t an issue, I suppose.

I have seen comment suggesting that some people take exception to being lectured about colonialism and white privilege. I can’t say that I blame them: it isn’t helpful. We none of us can change the past; and as I pointed out earlier, nobody alive today is responsible for what happened when NZ was colonised. I’d add that none of us is responsible for our skin colour or our ethnic provenance, so it’s as objectionable to (metaphorically) beat pakeha about the ears for being pakeha, as it would be to do the same to Maori.

Teaching kids to budget and cook healthily would be better investments.

We do better than most countries in how we treat our native population Martin.

I WOULD MAKE ENGLISH COMPULSORY!

I took a compulsory French class at school in the 70s. Dad didn’t backlash against it, didn’t rail against the French tongue. The backlash against Te REO Maori would be racist in motivation. Anyway the French class was difficult and hard to contextualise. Maori would have been better. Us Maori kids used to try and learn from a Tuhoe student in an off curriculum folksy attempt at an education. SAD eh?

+100 …well said…I compulsorily learned French …but would have found far more relevance learning Maori…I do not regret the French but the Maori would have been a Taonga…a personal Treasure to me

…if this government does nothing else it should make learning Maori compulsory in all schools …and NZ History and Civics and enrolling all student on the Electoral Roll

It feels a bit early in the government’s term to be raising this.

+100 …interesting Post….my inclination would be to make it compulsory however

I don’t believe in the word compulsory. Schools are not prisons. This generations accent is set by the English language which cause discomfort when Māori place names are pronounce towel-runga instead of Tauranga. We should not be teaching New Zealand children how to be inbread hill billies, paaaaaa. We don’t won’t to be more like Americans, we want students to have a basic level of geography and call it a victory.

…I would also make New Zealand History and Geography compulsory

…and for many of us learning another language apart from English was compulsory…in my case I had to learn French…imo it should have been Maori

include compulsory Civics under compulsory NZ History …and all kids enrolled to vote by the time they leave secondary school

“Getting tangled up in making it compulsory is missing the opportunity to progress while requiring focus on the structural racism that blights NZ.”

Agreed with you on this one Martyn.

My two children grew up in Canada after we fled NZ in 1987 from “Rogernomics’ and found Canada has made “french language also a “compulsory language too, and it didn’t work there but instead caused a backlash from being forced to use another language so “compulsory’ does not work now for sure.

best to take the people with you on this one.