GUEST BLOG: Tadhg Stopford – Ruthenasia, honoured. Why?

To my horror, I see Ruth Richardson got the Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit last year.

Personally, I can’t reconcile that with the consequences ofher ‘reforms’. It has been 35 years since “Ruthenasia” – changes so disruptive they helped drive the shift to MMP – yet many of us don’t understand what those policies did to the country

Is it too early to say they didn’t pan out?

Poverty has risen. Public infrastructure is visibly in deficit. Essentials cost more. Young people leave. Meanwhile, private monopolies thrive. Australian owned banks and supermarkets report world leading profits from our small market. Mining companies pay very low royalties to extract gold and other resources. Our “blue gold” – water – is exported ultra cheaply too.

So what exactly is the “public service” achievement we are honouring?

Public service is supposed to leave the next generation stronger. With reliable hospitals, affordable homes, sound infrastructure and higher productivity. Real public service builds a country that grows more secure over time, not more fragile.

Did Ruthenasia build that future?

For over three decades weve been told “fiscal discipline” means responsibility: shrink the state, trust markets, and let private finance allocate capital more efficiently than government. We were promised we would be leaner, richer and more productive.

Instead, we have record house prices, deferred maintenance, strained hospitals and households carrying more debt than ever.

So it seems reasonable to ask what that discipline has delivered – and for whom.

But first, a simple question: where does money actually come from?

For many people it’s a surprise to learn that it’s created ‘ex nihilo’, (out of nothing).

As the Reserve Bank of New Zealand explains, (see Money Creation in New Zealand)nmost money today enters the economy when commercial banks issue loans. In other words, most “money” is bank *credit*.

Whoever creates that credit largely determines what gets built. This is a vital point, and it explains our nations decline in productivity and wealth since ruthenasia. Because, effectively, we can no longer invest in ourselves.

Around the world, countries that treat credit creation as a public tool tend to build things.

The United States used national finance under Alexander Hamilton. Germany, Japan and Korea relied on state / public backed banks to industrialise. China still funds infrastructure through large public policy banks.

But countries that outsource (abdicate?) credit creation to private lenders tend instead to inflate assets, accumulate household debt, and export their wealth as someone else’s profit.

A little known historical fact is that Britain’s Currency Act of 1764 was instrumental in kicking off the American revolution. Because, like ruthenasia, it removed local money power, forcing colonial dependence on external creditors and constraining their self-development. Unlike kiwis, the Americans saw that for what it was.

For much of the 20th century, New Zealand followed the path of self development.

Railways, power stations, state housing and wartime mobilisation were publicly financed. Public credit built public assets. That is how young nations grow.

Then Parliament suddenly changed the rules.

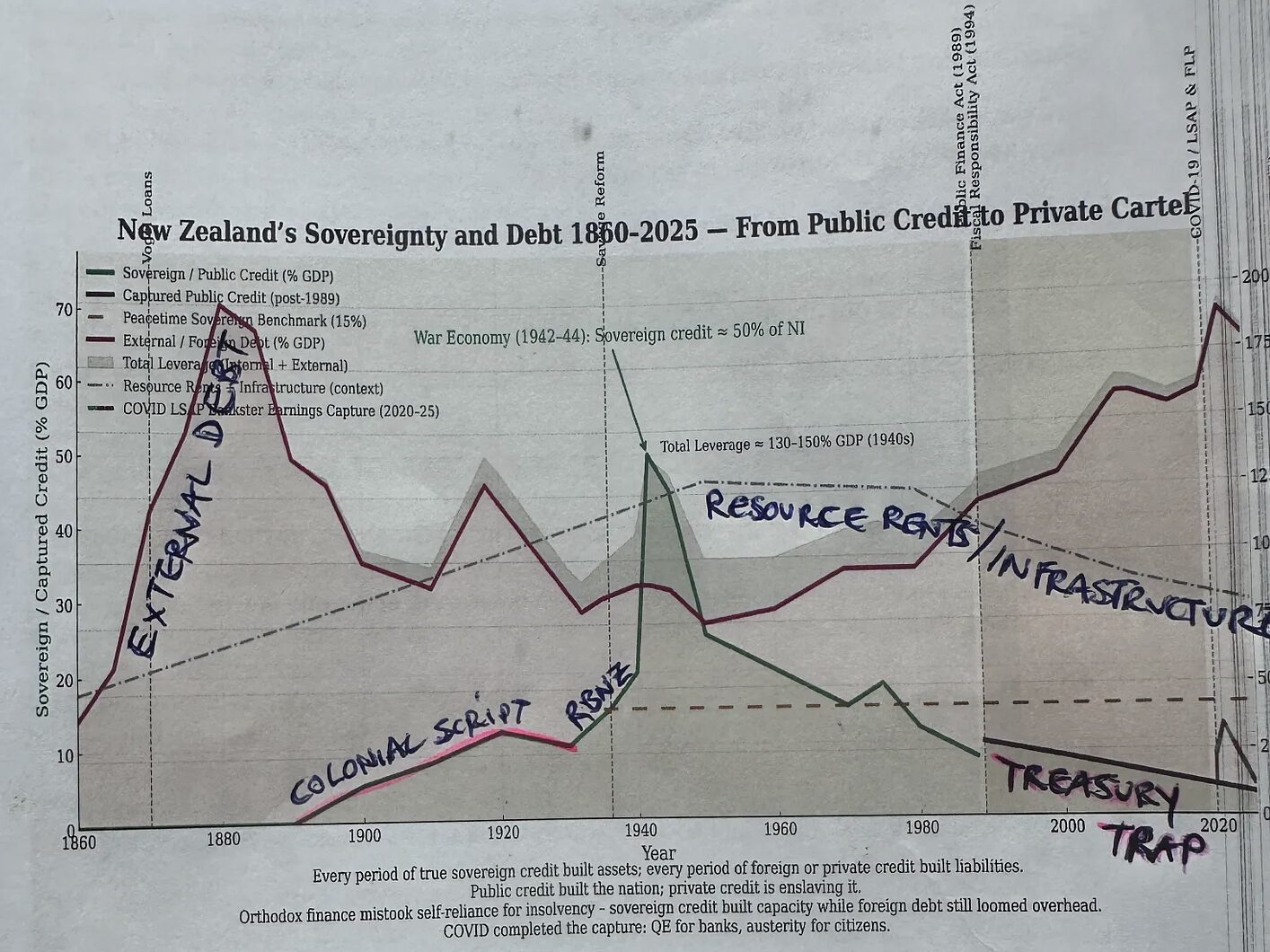

Between the late 1980s and mid-1990s, the Reserve Bank Act, Public Finance Act and Fiscal Responsibility Act reframed government from builder to bookkeeper.

Investment was treated as “spending”. Borrowing became something to minimise. ‘Balanced budgets’ became the goal.

At the same time, private banks became the dominant creators of new money. And banks, quite rationally, lend mostly against housing rather than pipes, hospitals or water systems.

The private sector does not provide public goods.

Credit follows collateral. Collateral is property. Prices rise. Debt rises. Profits flow to lenders rather than productive investment.

Even our measuring stick reinforces this bias. Statistics New Zealand’s Consumer Price Index excludes land and house prices – the very assets most credit flows into. We target consumer inflation while overlooking asset inflation. Meanwhile, cheaper prada bags, electronics, and holidays further obscure the rising costs of essentials. Keeping the rbnz from reining in the real cost of living.

In older language, those are false weights and measures. I call it the Treasury trap: (see graphic) if you measure the wrong thing, you make the wrong decisions; and you get bad outcomes.

Just rule requires honest measures.

The consequences are visible everywhere: boil-water notices, crowded wards, ageing infrastructure, young families locked out of ownership, and tens of thousands leaving for Australia each year.

But we did not forget how to work. Ruthenasia changed where the money goes.

Recent history shows the constraint was never purely financial. During Covid, tens of billions of dollars were mobilised within weeks. When government chose to act, the money was there. The limit is political design, not national capacity.

And that design was advanced by identifiable institutions and interests. Privatisation benefited merchant banks and asset buyers. Treasury and Reserve Bank reforms limited public investment while private credit expanded. Business lobby groups argued for shrinking the state’s building role.

The result is simple: public capacity shrinks, private lending expands, and families carry debts the state once carried.

Infrastructure falls behind, privatisation follows.

This is not a left v right argument. It is about stewardship (public service) vs corruption.

Every successful country treats credit as a nation building tool. We treat it as something to fear while handing its creation to banks for property speculation.

These settings are not laws of nature. They are legislation. Parliament can rewrite them.

New Zealand issues its own currency. We are not a household. We are a currency issuer. Our dollar is a national monopoly that has been almost entirely privatised.

The question is not whether we can afford to invest in ourselves, but whether we choose to.

Our problem was never that we built too much. It is that we stopped building for ourselves, sold assets cheaply, and now rent them back at higher cost.

The Treasury trap was a choice made 35 years ago. Undemocratically. Without our consent.

Discarding it is also a choice. Or it would be, if any politician were prepared to offer it.

If public service means leaving the next generation stronger than we were, it is reasonable to ask whether that eras efforts deserves honours, or repudiation.

Tadhg Stopford is a historian and teacher. Support change by purchasing your CBD hemp CBG at tigerdrops.co.nz

Gawd, no boats is wearing Ruth’s hand me downs