Ben Morgan’s Pacific Update: Pacific Summary 2026

An annual assessment of the security situation in the Pacific, including my thoughts about the key trends and concerns in 2026.

Historically, security discussions in the Pacific revolve around Sino-American competition, and the positions of both China and the US were well-understood. However, since last year’s assessment, the Trump administration’s foreign policy has involved a retreat from the US’s historic positions. A change that will impact on the Pacific’s security situation, producing a range of consequences.

Meanwhile, nations in the Pacific struggle to keep pace with the impact, seeking new economic and military partnerships and arming themselves creating uncertain and dangerous dynamics in the region.

How US foreign policy has changed

Previously, American foreign policy was based on a set of clearly articulated principles like; free trade, universal human rights and expanding democratic governance. Principles that can be termed ‘cosmopolitan’ and were consistently stated by all US leaders since World War Two.

Since the election of President Trump, the situation has changed and the new administration’s foreign policy appears to be based on principles that its supporters might describe as ‘pragmatic’ or ‘realistic’ and can be summarised as follows:

- Mercantilism. The idea that a primary objective of US foreign policy is profit. A position that rejects the idea that global ‘free trade’ is a basis for all nations to prosper, and instead focuses on maximising the US benefit of trade relationships.

- Bilateralism. That the US should reject multilateralism and international institutions. Instead, US international relations should be conducted on a case-by-case basis because a bilateral relationship maximises the bargaining power of the larger partner.

- Might is right. That a philosophical concept like ‘international law’ is unsupportable and unrealistic. Consider Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s famous statement, that “rights are nonsense, and natural rights are nonsense on stilts.” Essentially, that intellectual concepts like a ‘rights,’ ‘law’ or ‘justice’ are only made ‘real’ by the ability to enforce them. The Trump administration’s strategists argue that the US is unwilling to accept the cost of enforcing international laws or protecting the sovereignty of smaller nations. A position that inherently abandons the concept of universal, international principles of law and justice and retreats to an older ideology that ‘might is right.’

The proponents of this type of foreign policy argue that these principles are pragmatic, and that basing foreign policy decisions on cosmopolitan philosophical concepts is nonsense. Some examples of recent US foreign policy decisions indicative of this change are:

- The sudden imposition of punishing tariffs on friendly states, ignoring historic relationships and alliances.

- Stating that Canada, then Greenland should be part of the US and threatening to acquire both territories by force.

- The administration’s scathing criticisms of its European allies, and disregard for collective security in Europe.

- The unilateral decision to bomb Iran’s nuclear programme.

- An unexpected review of US commitment to the AUKUS programme.

- Staging a military operation in Venezuela to capture the nation’s president.

The US’s change in policy is not only demonstrated in its actions but also in the 2025 National Security Strategy,[i] a manifesto for change that confirms this approach. This change forces all Pacific nations to manage a new strategic reality.

The basics of Sino-American competition

In recent decades China’s economic and military power has grown enormously and the People’s Liberation Army is now a near-peer competitor of the US. China concentrates on an ‘asymmetric’ approach to military competition, developing and building large numbers of long-range missiles that can swamp the air defences of US carrier or amphibious task groups. This strategy is referred to as ‘area-denial’ because it denies America the ability to deploy its powerful carriers in China’s area of operations.

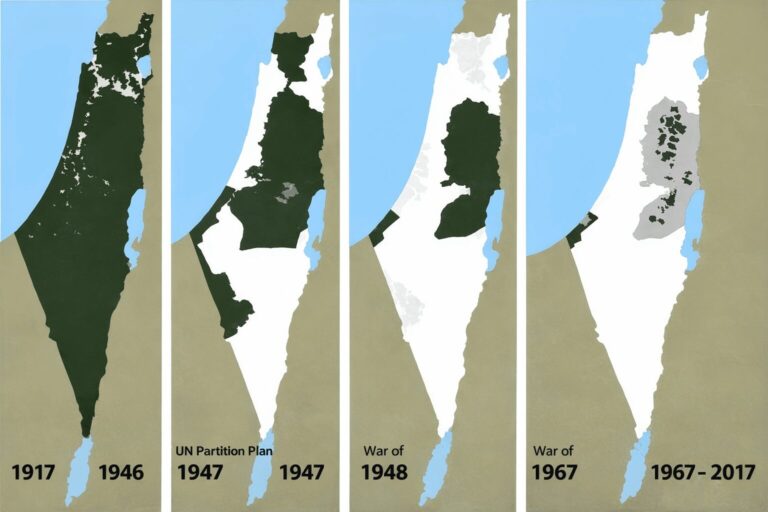

Traditionally, American military strategy concentrated on isolating China behind a barrier of allies and partners within the ‘1st Island Chain,’ that includes Japan, Philippines and Taiwan. American bases are located throughout the ‘1st Island Chain, ‘and strategic depth for the encirclement is provided by US bases in Micronesia to the east, and by its alliance with Australia in the south. Additionally, the Straits of Malaca are an important shipping route that links the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The straits are controlled by Singapore and Malaysia, both members of the Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA). The FPDA includes US allies and partners Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. See the map below.

This situation means China’s key strategic military consideration is protecting access to maritime trade. Therefore, China’s diplomatic and military strategies revolve around ‘breaking out’ from the ring of US allies and partners that surround it. Looking at the map it is easy to see why China is committed to securing the ‘9-Dash Line’ in the South China Sea because bases in this area could defend maritime trade through South East Asia. China also claims a large part of the East China Sea and Taiwan and is building influence in Micronesia, Melanesia, and the Pacific, expanding its options for access beyond the ‘First Island Chain.’

China’s new advantage

The Trump administration’s current foreign policy undermines America’s advantage, the strength of its relationships with it allies. For example, some of the administration’s first actions were to publicly berate its closest allies, verbal attacks that were followed by the imposition of punishing tariffs. Later, the administration’s threats to occupy Canada and Greenland are further demonstrations that the Trump White House is not ‘playing by the rules.’

The 2025 National Security Strategy, does highlight the defence of the ‘1stIsland Chain’ and blocking China’s claims on the South China Sea.[ii] But, the document’s language is notable because it demonstrates the US’s transactional approach stating that “Our allies must step up and spend—and more importantly do—much more for collective defense. America’s diplomatic efforts should focus on pressing our First Island Chain allies and partners to allow the U.S. military greater access to their ports and other facilities, to spend more on their own defense, and most importantly to invest in capabilities aimed at deterring aggression.”

Essentially, the strategy confirms that American support is conditional rather than a commitment based on shared philosophical principles. Conditional, transactional relationships are not strong, and current US foreign policy undermines existing alliances that took decades to build. Countries around the Pacific asking whether they can depend on US support and if the answer is uncertain, they may look elsewhere for economic or security support.

China and India are the obvious choices and January’s announcement of a large Sino-Canadian trade deal is an example of how US foreign policy has undermined an historic relationship. When Canada’s Prime Minister, Mark Carney travelled to Beijing to sign this agreement he became the first Canadian leader in a decade to visit China. A thaw in the two countries relationship directly attributable to American foreign policy.[iii] Carney’s Canada has accepted that the US is an unreliable business partner and therefore is pivoting economically towards China.

Canada’s pivot is economic and makes little difference to military competition but it highlights a risk to the US and is indicative of a wider trend. Already, other US allies are seeking trade deals with China or India and sidelining America.[iv] Trump’s recent threats about trading with China will probably amplify this trend. While China’s strategy of staying quiet and projecting stability is likely to pay dividends.

Strategically, China wants to break out of the 1st Island Chain and its activity across the region is focussed on this goal, from dominating the South and East China Seas to securing potential bases in the wider Pacific. Further, China is willing to operate slowly, patiently investing time building relationships that secure access to bases and sea lanes.

Notably, the Pacific is full of small nations, that have less historical connection with the US than Canada or its NATO allies. Factors that make them more likely to engage economically with China, or consider closer security relationships. US foreign policy means that China does not need to do much to look like a better potential partner than Trump’s America.

In recent years, China has been very active in the Pacific and even secured unexpected security deals with Solomon Islands and Cook Islands. Additionally, China’s police are supporting local law enforcement in several Pacific nations. The evolution from aid funder or economic partner to security partner is notable, indicating a high-level of trust. This series of interactions could potentially build China’s ability to project military power beyond the ‘1st Island Chain.’

In April, President Xi and Trump will meet to negotiate a new trade deal. The meeting will provide important insight into security in the Pacific. The meeting is Xi’s chance to ‘look the US president in the eye’ and asses his strengths and weaknesses. Xi will prepare meticulously and currently ‘holds better cards’ because Trump has already retreated in 2025 over tariffs and his recent back down over Greenland will be noted and studied by Chinese analysts.

My assessment is that this meeting will probably de-escalate military tensions because it will confirm to Xi that he can achieve his strategic goals without using force. But it is also possible that it will further expose the weaknesses of the Trump administration and increase Xi’s willingness to take risks. Only time will tell, but either way we should expect China’s influence in the Pacific to increase in 2026.

US foreign policy reveals a protentional weakness, that may impact Pacific security considerations

The raids on Iran, Nigeria and Venezuela all demonstrated the tactical-level capabilities of the US. However, each was clearly planned to minimise risk to US personnel and avoid long-term military commitments. In Trumpian terms, they could be interpreted as operations designed to maximise ‘bang for buck.’

However successful these operations were, this approach could demonstrate to potential opponents that the US is not willing to engage in sustained combat operations. A reasonable assumption considering President Trump campaigned on not committing to new ‘for ever’ wars, and keeping US troops at home. An implicit message of the operations is that the Trump administration is not going to commit to a sustained military operation. A potential strategic weakness that can be exploited.

Venezuela provides an example. A very effective special forces operation was followed by…. nothing. If the objective was regime change it does not matter that Maduro is in custody because his regime is still running Venezuela. Forcing regime change means defeating state institutions like the Venezuelan military, and this requires a sustained military operation.

Likewise, if the objective was to secure Venezuelan oil, American oil companies are unwilling to return to the country because it remains unsafe. Re-opening Venezuela’s oil fields is going to require a security force, probably US troops. Therefore, the fact that Trump has not deployed military force to secure either possible objective sends the message that his administration is avoiding sustained military operations.

Trump’s Greenland threats reinforce this interpretation. The president made lots of threats about acquiring Greenland, including using force. Europe demonstrated its resolve by flexing its economic power[v] and by deploying soldiers to Greenland. A physical ‘tripwire’ that Trump was unwilling to cross, forcing him to retract any threat of force.[vi]

The emerging picture of Trump’s US is unflattering. An unpredictable nation that is willing to ‘flex its military muscles’ in low-risk interventions but is unwilling to risk sustained military operations. In short, a nation that can be deterred militarily. If China did use force – Would the US fight to evict a Chinese force from Taiwan? Or from one of the Senkaku Islands? Or from the Solomon Islands? We do not know, and the 2025 US National Security Strategy implies that the decision would ‘put America first’ and be made on a case-by-case basis providing a little guidance.

This uncertainty about American military responses makes the Pacific region more volatile because it inevitably leads strategists in China and other nations that oppose the US to re-consider the risks of using force.

A ‘middle weight’ power’s arms race in the Pacific; Japan, Australia and Europe

Currently, international security discussions are driven by two considerations; China’s increasing assertiveness, and uncertainty about US commitment. A situation that encourages ‘middle weight’ powers to spend more on their own militaries, and to seek new alliances. In the Pacific, Japan and Australia are rapidly evolving into the northern and southern buttresses of the ‘Western’ security alliance. Meanwhile, European powers and NATO remain committed to the region because of their concerns about China.

Japan

In 2025, Japan massively increased defence spending, [vii] a strong indication of its security concerns. Japan also demonstrated a new forthrightness with regards to China. For example, Japan’s elite marine brigade moved south, closer to Senkaku Islands that neighbour Taiwan in July[viii] and its amphibious warfare capability continues to grow,[ix]demonstrating the nation is considering projecting military force to protect its island chains.

Previous Prime Minister Ishiba committed to Japan becoming stronger, and more engaged with its defence partners the US, Australia and South Korea which translates into a more active security role in the Pacific. For example, Japanese participation in Australian military exercises and working closely with Australia and the US to conduct ‘freedom of navigation’ patrols supporting the Philippines as it confronts Chinese claims in the South China Sea.

Notably, in November Japan’s Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi spoke in parliament and linked the security of Taiwan to Japan.[x] A statement that caused diplomatic outrage in China but that indicates Japanese willingness to confront Chinese assertiveness. Japanese politicians challenging Chinese narratives are a signal that Japan’s perception of it role in security discussions is changing.

Japan’s role in the Pacific is evolving because it has military power,[xi] a strong industrial base and is committed to deterrence by working more closely with its allies and partners, specifically Philippines, Australia and New Zealand. Defence agreements, exercises, technology alliances, intelligence sharing and joint naval activities are becoming common between this group of countries. A trend that is likely to continue, especially if the US becomes less predictable forcing middle-weight powers like Japan to assume greater leadership roles in Pacific collective security arrangements.

Australia

Australia was another country highlighted in last year’s Pacific Summary,[xii] and this year the nation’s importance in the region continues to increase. Australia has a longer history of leadership in collective security arrangements, and has tacit US approval to play this role in the South West Pacific. For instance, Australia leads the biggest international military exercise in the South West Pacific. Australia’s leadership role also includes training its neighbours and developing their inter-operability. Since 2024, New Zealand, Papua New Guinean and Fijian senior officers have held deputy command positions in Australian Defence Force organisations helping promote greater inter-operability between these nations.

Like Japan, Australia is concerned about China’s increasing assertiveness so is increasing defence budgets. It is especially interested in developing its domestic defence industries. Australia is building a wide range of military equipment from small arms to long-range missiles and ships. Notably, Australia’s version of the Boxer armoured vehicle was recently purchased by Germany, an indication of the defence industry’s sophistication.

Australia also regularly hosts large contingents of NATO and US ships, aircraft and soldiers for exercises. Exercises and rotations of military personnel are designed to encourage inter-operability, Australia practicing working together with a wide range of allies and partners in preparation for potential joint operations, some of which are likely to be led by Australia.

Another role Australia fulfils is serving as a ‘launch pad’ for US or NATO forces deploying into the Pacific. In recent years, Australia invested heavily in defence infrastructure like airfields, accommodation, ports and communication hubs. A programme that continues and includes plans for improved air defence capabilities, like the Medium Range Ground Based Air Defence programme. Australia is becoming a secure logistics hub with the facilities to disembark, sustain and protect a large US or European force deployed to the Pacific.

Last year, Australia signed a new defence agreement with Indonesia.[xiii]Although avowedly neutral, Indonesia is a key security player in South East Asia, the South China Sea and Melanesia. By strengthening its security relationship with Indonesia, Australia indicates it is keen to maintain or extend its interests in South East Asia. Indonesia may be neutral and have a good relationship with China, but the two nations are at odds about territory in the South China Sea and this deal also suggests Indonesia is keen to ‘hedge its bets’ by building a security relationship with Australia.

Europe / NATO

NATO’s 2022’s strategic concept identified China as a threat to Europe stating that “The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values,” and then discussed the developing relationship between the alliance and its Indo-Pacific partners, Australia, South Korea, Japan and New Zealand.

Throughout 2025, NATO countries continued to conduct training and other activities in the Pacific. NATO navies conducted ‘freedom of navigation’ patrols in the East and South China Seas and Taiwan Strait. During Talisman Sabre 2025, NATO aircraft, warships and soldiers exercised in Australia. Meanwhile, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand’s militaries working more closely with NATO. For example, sharing technology, providing intelligence, helping train Ukrainian soldiers and participating in exercises.

This trend includes the development of bi-lateral arrangements between partners in the two regions, as countries look to new security partnerships because they are worried by both US and Chinese activities. In January 2026, Italy and Japan signed an agreement elevating their relationship to ‘strategic partnership’ status. [xiv] Euro News reports that “In their joint declaration, the leaders expressed “deep concern about all forms of economic coercion and the use of non-market policies and practices and the use of export restrictions that disrupt global supply chains,” language directed at both China’s export controls and Washington’s protectionism under US President Donald Trump.”

In summary, 2026 will be a year defined by the ‘middle weight’ powers seeking greater economic and military security by working together. This year expect to see NATO’s military presence in the region to increase including more bi-lateral agreements between European states and their Indo-Pacific partners. European states keen to shore up defence arrangements with military powers like Japan, Australia and South Korea.

Australia’s role as a regional security leader will continue to increase. Additionally, Japan and Australia’s security relationship will become stronger, so expect to see more Australian ships and aircraft heading north to operate in joint task forces in the South and East China Sea. Likewise, expect to see more Japanese ships, aircraft and soldiers active in Australia’s South West Pacific area of interest.

AUKUS

AUKUS is probably the most important defence arrangement in the Pacific region because it significantly increase the number of nuclear power submarines available to the US and its allies. Submarines are increasingly important because unlike surface vessels they cannot be targeted by long-range missiles so can operate within Chinese area-denial zones.

As predicted in last year’s summary, President Trump did not stop the AUKUS deal. After a review, the Trump administration is now committed to AUKUS.

Currently, drones are re-writing the rules of naval warfare and the submarine environment is no exception. The AUKUS submarines will operate supported by Uncrewed Vessels like Ghost Shark, and the programme’s technology sharing arrangements could be used to allow allies and partners to remain inter-operable and militarily competitive. So, it is likely that countries like Japan, South Korea and possibly New Zealand will join the programme.

Key ‘Hot Spots’ – Areas to watch in 2026

Taiwan

In 2025, Chinese activity around Taiwan continued to increase including large exercises and aerial intrusions testing defences and threatening the island. In December, China conducted a new form of activity that involved hundreds of fishing boats conducting large, synchronised manoeuvres near Taiwan that some commentators suggest could be practice for forming blockades.[xv]

However, my assessment is that it remains unlikely that this tension will escalate into kinetic war-fighting. Taiwan’s strong defence force and geography make it an exceptionally tough target. Additionally, an invasion would certainly be opposed by Taiwan’s local allies Japan, South Korea and Philippines. Australia is likely to support Taiwan, and although a US intervention can no longer be taken as a certainty, it is highly likely.

Further, China has a key strategic weakness – maintaining its access to trade. Pro-Taiwan nations surround China so its maritime trade is easily blockaded. This makes an invasion highly unlikely before China has secured access to its most important trade routes. In my opinion, control of the South and East China Seas is a pre-requisite for an invasion attempt.

South China Sea

The South China Sea remains tense, a situation that is unlikely to change in 2026. China continues to enforce its claim over the sea known colloquially as the ‘9-Dash Line.’ China’s claim is not internationally recognised but the nation still enforces its claim to occupy islands, shoals and reefs within the South China Sea.

In the long-term, control of the South China Sea is essential for China because it secures the nation’s trade routes. In my assessment, the South China Sea is far more important to China strategically than re-occupying Taiwan. Therefore, I expect that China’s slow inexorable push into the South China Sea will continue in 2026 and will remain focussed on Philippines. In turn, this will force more confrontations as nations like Japan, Australia and the US support Philippines to deter China’s actions.

In the unlikely event that China does risk taking territory by force in 2026, possibly to test America’s response, my assessment is that its most likely to be in this area. The region has several small easily occupied islands, ideal for a test of resolve because escalation can be contained more easily than in a larger operation.

North Korea

China influences North Korea because without its neighbour’s aid its economy would collapse. Strategically, North Korea plays the role of a nuclear armed ‘wild card,’ it is a threat that is hard to judge and creates uncertainty for US policymakers. But my assessment is that Chinese strategists understand a threat is most powerful, when it is not used. Currently, China is winning the war for international influence and last thing it needs is its client state creating instability so there is little risk of war on the Korean Peninsular in 2026.

Melanesia

Melanesia is a region that is seldom discussed in mainstream media but has a variety of factors that make it inherently unstable. The region is an archipelago of large and small islands that are rugged and un-developed. Its nations are young and poor so state institutions are weak encouraging crime and corruption. Melanesia has vast resources including oil, hard wood timber, fishing grounds, rare earth minerals, copper and gold.

The region is also a politically complex area with several indigenous groups seeking independence. In 2024 there was an outbreak of political violence in New Caledonia. Meanwhile, the long running war Indonesia is fighting in West Papua / Irian Jaya continues, and Bougainvillian independence is being discussed in Papua New Guinea.

A notable and unique risk is that the region’s nuanced politics are mis-interpreted by the US and its allies, that do not always appear to appreciate the independence of Melanesian perspectives on key issues. For example, the US and Australia being taken by surprise by the 2022 Solomon Islands security partnership with China. A situation that sometimes leaves locals feeling alienated by historic colonial powers like the US and Australia, providing opportunities for China to expand its political influence.

Melanesia is a complex and dangerous area that is currently subject to Sino-Australian competition. In my opinion, military (or para-military) conflict is more likely in this region than anywhere else in the Pacific. The combination of its existing complexity, and the area’s general lack of visibility mean it is a place in which ‘grey zone’ competition could easily develop. The region’s ruggedness, remoteness and lack of visibility mean that if conflict develops it could escalate more quickly than in other areas that are more closely monitored.

Access to the Poles

Although, the poles are seldom discussed in mainstream media the polar regions are full of natural resources and the Artic is important because it provides an alternative maritime trade route.

The North West Pacific it borders the Arctic region so expect to see more activity to secure key territories that secure access to this area. Places like the Bering Strait, St Lawrence Island, the Kuril Islands, Alaska and the Aleutian Islands being discussed more from a security perspective.

The Antarctic is also not discussed often but is resource rich and there is increasing scientific interest in the region. Both Russia and China expanded their exploration programmes in 2024 and 2025.[xvi] Meanwhile the Trump White House cut funding for the US Antarctic programme.[xvii]

And, for anyone interested in the Artic or learning more about icebreakers check out Sixty Degrees North on Substack.

Conclusion

Pacific security discussion continues to revolve around Sino-American competition, and in 2026 the Trump administration’s foreign policy is making the US less competitive. Current US foreign policy has damaged historic relationships and creates uncertainty.

And, uncertainty is the key feature of 2026 and nations across the Pacific are struggling to manage it. China is advancing its influence, presenting itself as a reasonable and predictable alternative to the US. In my opinion, China is most likely to maintain this policy in 2026 because it is already winning the ‘soft war’ for influence with minimal effort. It does not take a great strategist to see that military action would be detrimental to China’s programme of relationship building. Therefore, I believe it is unlikely that China, or its proxies will initiate military operations like invading Taiwan in 2026.

However, US foreign policy has created great uncertainty and recent activities indicate the Trump administration does not want a sustained military operation. This may change Beijing’s appetite for risk.

The Pacific’s small nations, faced with uncertainty are looking for economic and security partnerships with larger nations. Some will choose China or India, others Australia, Japan or the US. The ‘middle weight’ powers are arming themselves and building new collective security arrangements to fill the void left by the US.

In conclusion, 2026 will be an unpredictable year in the Pacific.

Thanks for reading my work. If you like this content and want to support it you can ‘Buy me a Coffee’ here – buymeacoffee.com/benmorgan

[i] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

[ii] ibid pp 22-23

[iii] https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/

[iv] https://www.cnbc.com/2026/01/

[v] https://www.bbc.com/news/

[vi] https://www.bbc.com/news/

[vii] https://www.aljazeera.com/

[viii] https://benmorganmil.substack.

[ix] https://benmorganmil.substack.

[x] https://benmorganmil.substack.

[xi] https://www.intellinews.com/

[xii] https://benmorganmil.substack.

[xiii] https://www.aljazeera.com/

[xiv] https://www.euronews.com/2026/

[xv] https://www.nytimes.com/

[xvi] https://www.abc.net.au/news/

[xvii] https://www.csis.org/analysis/

Ben Morgan’s Substack is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell Ben Morgan’s Substack that their writing is valuable by pledging a future subscription. You won’t be charged unless they enable payments.

Ben Morgan is a bored Gen Xer, a former Officer in NZDF and TDBs Military Blogger – his work is on substack