MEDIAWATCH: AI Bryce at his best

This is AI Bryce at his best…

These are all “broken markets” contributing to the “broken New Zealand” we are currently experiencing. There’s rising public discontent about this oversized corporate power and how it is exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis. But can we do anything about it? Will politicians do anything to fix these uncompetitive markets?

There’s a glimmer of hope in the Government’s current proposed reform of the Commerce Act 1986. It might sound boring, but the “Commerce (Promoting Competition and Other Matters) Amendment Bill” is the most significant competition law reform in nearly two decades, and could potentially make a real difference in reining in the monopolistic behaviour that characterises the New Zealand economy, reducing growth and productivity.Yet, the proposed reforms have already been watered down, and there’s a real chance they might be further neutered by the lobbying of vested interests, who are currently complaining that even these very moderate government proposals would be too hard on big business.This fight over business oligopoly practices is flying under the radar at the moment, but needs more attention. The issue is urgent, because submissions to the Select Committee on the Government’s proposals close tomorrow at midnight (11:59pm, Wednesday 4 February). And unfortunately, the process is likely to be dominated by big businesses, business associations, and corporate law firms, who are pushing to retain as much of the status quo as possible.Why This Reform Has Come AboutNew Zealand has been grappling with unusually concentrated markets in key sectors, leading to higher prices and fewer choices for consumers. A series of Commerce Commission market studies in recent years underscored these problems: Groceries (2022), Fuel (2019), Building Supplies (2023), and Banking (2023). These studies signalled that current laws and tools were not sufficient to ensure healthy competition. The public’s cost-of-living pain — and knowledge that a handful of big companies were reaping fat profits — created a strong political imperative to “do something” about entrenched monopolies and duopolies.Awareness that “the system is rigged” in favour of greedy business has led to a surge of advocacy for market reforms from almost across the political spectrum. This was crystallised further by a damning OECD report (“Revamping Competition in New Zealand”) published in August 2024 that showed New Zealand’s competition settings have contributed to productivity “markedly below the OECD frontier.”The last Labour Government had already initiated a reform agenda in this area, and this was picked up in 2024 by then Commerce Minister Andrew Bayly. He’s been strongly supported by Finance Minister Nicola Willis, who has emerged as an outspoken advocate for tackling “dysfunctional markets.” Her strong support for the bill is in line with her stance that National must stand up to corporate giants on behalf of consumers. National sees a political upside in being tough on monopolies, shaking off their “friends of big business” image.However, not all in the coalition see the fight against oversized corporate power so positively. NZ First is solid in its support for reform in this area. Some in National are less enthusiastic, and further to the right, the Act Party worry the reforms go too far in regulating business and interfering with the free market.Therefore, the legislation proposed represents the minimum viable reform that improves competition enforcement without fundamentally threatening incumbent interests too overtly. Hence, the bill is likely to get almost total support from all parties in Parliament, including Labour and the Greens. The problem is that it has already been significantly watered down, and business lobbyists are currently pushing for this to go further.What’s Good About the Government’s BillThe most important elements of the bill are its crackdown on monopolistic tactics. New provisions explicitly target “creeping acquisitions” (serial buy-ups of smaller rivals) and so-called “killer acquisitions” (dominant firms buying startups just to eliminate them). In general, it lowers the threshold for the ability of the Commerce Commission to prevent mergers and acquisitions that might lead to a “substantial lessening of competition.”The bill also expands the test to include conduct that “creates, strengthens, or entrenches a substantial degree of power in the market,” bringing New Zealand closer to Australia’s 2025 reforms. This is crucial for catching acquisitions that don’t immediately lessen competition but build dominant market positions over time — exactly the strategy used by private equity firms rolling up veterinary clinics, funeral homes, and regional healthcare providers.Other positive provisions include strengthened market study powers (the Commission could recommend pro-competition regulation to Ministers), class exemptions for low-risk conduct, a notification regime for small business collective bargaining, corrective action orders allowing the High Court to restore competition after breaches, and new whistleblower protections.For these reasons, consumer advocates such as Consumer NZ and Monopoly Watch NZ have been supportive. Consumer NZ chief executive Jon Duffy has been among the most prominent voices commenting on the bill, saying it improves the current situation.Problems with the Government’s BillHowever, critics from the public-interest side argue the reforms, while positive, don’t go far enough. They worry the Government might tout this bill as “job done” on competition, whereas real market change — like actually fostering new competitors or breaking up monopolies — could stall.There are also significant missing elements from the proposals. First, when major mergers are occurring, it will only be voluntary to inform the Commerce Commission. In other countries, such as Australia, such notifications are mandatory above certain thresholds. This means the Commission must rely on its new “call-in” powers rather than having automatic visibility of potentially problematic deals.Second, the Government decided not to give the Commerce Commission the power to create sector-specific pro-competition industry codes, despite MBIE and the Commerce Commission both supporting this. Industry codes (used in Australia for dairy, energy, and grocery sectors) allow targeted intervention without requiring full legislation. Industry codes would have given the Commerce Commission real teeth to break down barriers without waiting for Parliament. Their absence means the Commission must conduct lengthy market studies and then wait for government to legislate, which is a process that can take years.Third, the bill includes problematic predatory pricing provisions that Labour MP Arena Williams rightly criticised as “the only pricing intervention where it’ll be illegal under National to put prices down.” The provisions use cost-based tests that could actually protect incumbent duopolies from genuine price competition when a third player enters the market. As Williams noted, consumers benefit when new entrants force prices down, making that illegal seems perverse.Fourth, the bill includes a 10-year Official Information Act exemption for confidential information supplied to the Commerce Commission. While some protection for commercial sensitivity is reasonable, 10 years is excessive, and creates an accountability gap.Finally, the Government has cut the Commerce Commission’s budget by $3.4 million while simultaneously expanding its powers. Commission chair John Small told a Select Committee in December 2025 that the Commission has already scaled back headcount and market studies. Expanding powers while reducing resources is a recipe for ineffective enforcement.Big Business Fights BackThe two big omissions from the legislation (mandatory notifications and industry codes) were successfully lobbied against by business interests. And now, as the legislation goes through the select committee process, big businesses and their representatives are actively pushing for further changes that will protect profits and market dominance. The narratives they are deploying to shape the debate revolve around “investor confidence,” “regulatory uncertainty,” and “process concerns.”Major law firms including Chapman Tripp, MinterEllisonRuddWatts, Russell McVeagh, and others have signalled they will submit detailed concerns on behalf of their corporate clients.RNZ is reporting the concerns of law firm Chapman Tripp, with two articles published in the last few days featuring Chapman Tripp’s competition and antitrust partner Lucy Cooper. According to an article by Nona Pelletier yesterday, the legislation “could disadvantage consumers, deter investors and increase the cost of doing business.”Chapman Tripp’s Lucy Cooper is quoted saying her first reservation is that the reforms “will add unnecessary uncertainty, time and cost to the Commerce Commission processes.” Her second concern is that “the Commerce Commission will get a lot more discretion or power without solid process protections, or the ability to really scrutinise its work.”Of course, these criticisms should be contextualised by the fact that Chapman Tripp specialises in helping major corporates with mergers and acquisitions. Their concern about “investor confidence” is code for: this will make it harder for our clients to consolidate markets through serial acquisitions. Cooper’s objection to “retrospective” application of creeping acquisitions provisions is also misleading — the Commission isn’t unwinding past deals, just considering their cumulative effect on current market conditions.Similarly, MinterEllisonRuddWatts has publicly stated that the expansion of the test for a “substantial lessening of competition” “could chill pro-competitive commercial behaviour.” And Russell McVeagh complains that existing tools to deal with anti-competitive behaviour are already sufficient, citing the Wilson Parking case as evidence. But that case actually proves the opposite — it took years of enforcement action, demonstrating that the Commission needs more tools, not fewer.On the new provisions to deal with “creeping acquisitions,” Russell McVeagh claims there is “not a clear evidential basis that this reform is required in New Zealand.” This ignores the supermarket duopoly making $1 million a day in excess profits, the banking oligopoly, building supplies concentration exposed in the 2023 market study, and the OECD’s finding that New Zealand lags international peers on competition metrics.The NZ Initiative and BusinessNZ are also expected to submit strong opposition to the reforms, representing their corporate clients and members.The “Rip-Off New Zealand” Problem RemainsThe Government claims it is tackling broken markets with the introduction of the Commerce (Promoting Competition and Other Matters) Amendment Bill. There’s some truth in this. But there’s also truth in the complaint from consumer advocates that aspects of this bill may protect incumbents while claiming to promote competition.The proposed legislative reform brings New Zealand closer to international standards but leaves significant gaps. For example, when compared to the more thorough commerce reforms in Australia, it looks like New Zealand is adopting the weaker parts of those reforms and skipping the stronger provisions.The bill is definitely a step forward, but its limitations are revealing. In particular, the choices to omit strong regulatory options — industry codes, mandatory merger notifications, price gouging prohibitions — probably reflect a reform process that has been shaped by the interests it purports to regulate. And the danger is that corporate lobbyists will weaken the legislation further over the coming months as it progresses through the Select Committee.If the bill’s limitations persist and enforcement remains under-resourced, the “Rip-Off New Zealand” problem — concentrated markets, excessive profits, captured regulators, and political unwillingness to confront incumbent power — will remain fundamentally unaddressed.As Labour MP Arena Williams noted in the first reading debate, this matters for democracy itself: “When people go to the checkout and they are paying more and more every week… it’s not only those large companies that they start to lose faith in; it’s the people who are elected who set the rules which govern them. It’s their democracies and it’s their institutions.” Broken markets breed broken trust in democratic institutions.

…AI Bryce is 100% right.

We refuse point blank to regulate capitalism in this country.

We have this issue in the under-regulated NZ economy with monopolies, duopolies and oligopolies taking over alongside a lack of investment into the infrastructure we need for rapid climate change adaptation.

I believe we should be tapping our ACC and NZ Super funds to directly invest in NZ alongside bringing in Māori Capitalism…

New report highlights dramatic growth in Māori economy

Māori contributions to the economy have far surpassed the projected goal of ‘$100 billion by 2030,’ a new report has revealed.

The report conducted by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s (MBIE) and Te Puni Kōkiri, Te Ōhanga Māori 2023, shows Māori entities have grown from contributing $17 billion to New Zealand’s GDP in 2018 to $32 billion in 2023, turning a 6.5 percent contribution to GDP into 8.9 percent.

The Māori asset base has grown from $69 billion in 2018 to $126 billion in 2023 – an increase of 83 percent.

Of that sum, there is $66b in assets for Māori businesses and employers, $19b in assets for self-employed Māori and $41b in assets for Māori trusts, incorporations, and other Māori collectives including post settlement entities.

In 2018, $4.2b of New Zealand’s economy came from agriculture, forestry, and fishing which made it the main contributor.

Now, administrative, support, and professional services have taken the lead contributing $5.1b in 2023.

Could Māoridom become the competitive friction against the self-interested Public Service that well regulated Capitalism demands?

I believe it could and deserves investigating by the Left.

Allowing Māori Capitalism to co-fund and co-own essential investment would be a step towards realising the promise of the Treaty while protecting NZ from foreign investment.

It was embarrassing that National organised an investment summit and forgot about Māori.

Daniel McLauchlan is one of the greatest political columnists in New Zealand and his critique of the NZ bureaucracy is worth reading…

The dogmatic political left invests its faith in the bureaucratic state; the dogmatic right trusts oligopolistic free markets – leaving New Zealand with crumbling infrastructure and corruption

…the Political Left have allowed the self-interested Public Service and the Professional Managerial Class to push self interested virtue signals rather than structural change and increased capacity of the State!

David Seymour says the Public Service is Left wing, bullshit!

If only this was true!

The Wellington Bureaucracy isn’t left wing! It’s a self interested Professional Managerial Class who use identity politics to mask their neoliberal hands-off-do-nothing-but-build-glass-palaces fiefdoms.

Oh they do the reo, and expose their pronouns and militantly ride bikes, they are effortless in their use of inclusion as a means to dominate and control the narrative, but they are a middle class clique, not left wing egalitarianism.

The Wellington Bureaucracy is a culture war of woke middle class Identity Politics aspirations backed with State funding, they may aesthetically be Left but they sure as fuck aren’t economically Left.

To brand the Public Service as ‘Left’ misdiagnoses the disease, symptom and patient!

The real power struggle in NZ isn’t Left vs Right, it’s between the Professional Managerial Class Corporate Consultants who influence policy to maintain their dominance and profit margins vs the self serving Public Service wanting to spend taxpayer money on their latest glass palace.

The Politicians are merely a masquerade of democracy to ensure participation that generates legitimacy, but the real power is between the Corporate Consultants who influence all policy to keep NZ deregulated and the self serving Public Service who are in it for their own fiefdoms.

The only chance any truly progressive movement gets in NZ politics is to ram your changes through in the first 100 days of any new Government.

That stops the self serving Public Service from stymieing your agenda and it stops the corporates from influencing it.

If we want true progressive policy to tax the rich and remove costs from peoples lives, it needs to be rammed through in the first 100 days or it won’t happen.

That’s why Labour have been so feckless and useless, they had no 100 day plan in 2017 and they didn’t expect to win an MMP majority in 2020 and had given up in 2023!

They effectively became captured by the self serving Public Service and the Corporate Consultants.

Daniel talks about the lack of actual competition to the self-serving Public Service and to that effect Māori Social Service Providers could easily become the competition the self serving Public Service needs while building State capacity with a Ministry of Green Works.

The lack of results from a self serving Public Service riddled with Corporate Consultants could finally be challenged by Māori Social Service Providers that treat everyone who comes, but in a Māori cultural setting.

That development can drive the self serving Public Service to be far more responsive and force actual results out of them.

It’s allowing regulated capitalism to inject the dynamic of competition while building State capacity.

Imagine a scenario where Iwi joined forces with the State to create a 3rd Supermarket Operator with a focus on lower costs to customers, better work conditions for workers and better prices for suppliers.

Or expanding existing community health groups that are open to the entire community but run within Kaupapa Māori.

Same with Māori schools.

You can generate the competitive friction Capitalism requires while building up the State, not denigrating it.

Right now we have over half a million Kiwis accessing food banks per month while the corporate slop in schools only provides food with barely any nutrition…

NZ school lunches ‘half the energy’ kids need – new research

…here is an opinion piece demanding we stop waiting for a foreign owner to step in and solve out Supermarket Duopoly…

Stop waiting for a foreign hero: NZ’s supermarket sector needs competition from within – Opinion

…I agree.

Let’s work with Māori Capitalism and build a fairer more equitable outcome that also protects essential infrastructure like food security while also adopting the values of a Green Post Growth economy.

The reality is that Billionaires are killing us on a burning planet and post growth Capitalism is here…

…in the words of Professor Wayne Hope from his new incredible book, The Anthropocene, Global Capitalism and Global Futures…

The corporate ambit of emissions culpability also includes transnational finance capital. In October 2019, journalist Patrick Greenfield drew from the think tank Influence Map and business data specialists Proxy Insight to examine the investment holdings of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street. Their combined portfolios presided over US$286.7 billion of oil, coal and gas company shares administered through 1 712 funds. These figures excluded direst and non-listed fund holdings. Such investments were, and are, used to manage major funds involving pensions, university endowments and insurance companies. These figures reiterate the general principle of corporate culpability for carbon emissions and point to the contribution of global finance. Further to this matter, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney surmised that multi trillion-dollar world capital markets were financing projects and activities likely to raise average global temperatures 4% more than pre-industrialised levels.

As global networks of fossil fuel extraction, refining, industrial use and related financial investment produce carbon emissions, wealthy elites dominate carbon consumption. Explaining the process first requires a short excuses on wealth distribution, luxury consumer culture and class. Clearly, global wealth growth benefits super-rich individuals from the TCC. The richest 1% of the world’s population took 38% of all additional wealth between 1995 and 2021. Just 2% went to the bottom 50% of humankind. For the same period, billionaires’ share of total global wealth grew from 1 to 3%. Tim Di Muzio, writing in 2015, depicted such differentials as a global plutonomy whereby economic growth powered and consumed mostly by the wealthy few, excluded the vast majority. With huge money surplus to spend on precious metals, property portfolios, home residences, retreats, first-class travel, cars, yachts, jets, exclusive cultural pursuits and leisure activities, the rich and super rich demarcate social prestige among themselves. Individuals, families and groups strive to symbolically out-consume their class peers, while the upper-middle classes aspire to emulate their superiors. The entire set-up, led by the dominant owners of capital, is ecologically unsustainable.

Although modest and poorer households also generate greenhouse gases through everyday activities such as shopping, commuting, food preparation and basic leisure activities, high-end discretionary consumption is more carbon intensive. Thus, economy class plane trips compared to first-class passages account for much less carbon dioxide per person. Luxury automobiles encourage a greater individual carbon footprint than standard vehicles, buses and trains. Counter-consumption campaigns such as eco-labelling for food and travel options have not shifted the prevailing pattern of carbon use inequality. As reported by Oxfam in 2015, the richest 10 of people produced half of the planet’s individual consumption-based fossil fuel emissions, while the poorest 50% contributed only 10%. The Top 1% emitted 30 times more carbon dioxide than the poorest 50% and 175 times that of the poorest 10%. The 2022 World Inequality Report broadly confirms these statistical trends and precedents a fascinating intra-class data. As of 2019 the richest 1% of individuals emitted around 100 tonnes of carbon dioxide on average, per person, per annum. More dramatically, those within the top .1% emitted 467 tonnes and the top 0.01% 2550 tonnes. The calculations demonstrate that high echelon gradations of carbon dioxide emission correlate with the gradations of capitalist class wealth. David Kenner’s research on overconsumption posits that rich one-percenters rarely make the link between luxury consumption and climate change impacts such as hurricanes, floods, heatwaves and forest fires. More commonly, they use “their extreme wealth to try and insulate themselves and continue their carbon intensive lifestyles”.

Let’s have a new deal on the Billionaire Class….

….and this too…

Who is brave enough to back Brazil’s global tax on billionaires? The answer will define our future

The response to the pandemic was one test of that proposition. Now the world’s governments face another. Last week, Brazilian climate minister Ana Toni explained a proposal put forward by her government (and now supported by South Africa, Germany and Spain), for a 2% global tax on the wealth of the world’s billionaires. Though it would affect just 3,000 of the super-rich, it would raise around $250bn(£195bn): a significant contribution either to global climate funds or to poverty alleviation.

Radical? Not at all. According to calculations by Oxfam, the wealth of billionaires has been growing so fast in recent years that maintaining it at a constant level would have required an annual tax of 12.8%. Trillions, in other words: enough to address global problems long written off as intractable.

You would need to perform Olympian mental gymnastics to oppose Brazil’s very modest proposal. It addresses, albeit to a tiny extent, one of the great democratic deficits of our time: that capital operates globally, while voting power stops at the national border. Without global measures, in the contest between people and plutocrats, the plutocrats will inevitably win. They can extract vast wealth from the nations in which they operate, often with the help of government subsidies and state contracts, and shift it through opaque networks of shell companies and secrecy regimes, placing it beyond the reach of any tax authority. This is what some of the global “investors” in the UK’s water companies have done. The money they extracted is now gone, and we are left with both the debts they accumulated and the ruins of the system they ransacked. Get tough with capital, or capital will get tough with you.

The Brazilian proposal, which will be put before the G20 summit in Rio in November, has already been dismissed by the US treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, who suggested there was no need for it. On whose behalf does she make this claim? Not ours. Wherever people have been surveyed, including in the US, there is strong support for raising taxes on the rich.

In the two years following the start of the pandemic, the world’s richest 1% captured 63% of economic growth. The collective fortune of billionaires rose by $2.7bn a day, while some of the world’s poorest became poorer still. Between 2020 and 2023, the five richest men on Earth doubled their wealth.

Billionaire wealth impoverishes us all: astonishingly, each of them produces, on average, a million times more carbon dioxide than the average global citizen in the bottom 90%. Billionaires are a blight on the planet.

Yet, because they are the true citizens of nowhere, shifting their wealth and residence between jurisdictions, they pay far lower levels of tax than the most downtrodden of their workers. Oxfam has calculated, using records unearthed by the investigative journalists ProPublica in 2021, that Elon Musk pays a “true tax rate” of 3.27%, and Jeff Bezos less than 1%. Falling tax rates and the clever workarounds designed by the lawyers and accountants serving the ultra-rich help to explain the growth of their fortunes.

Wealth that could otherwise support public services and public wellbeing is siphoned out of nation states. As the global rich accumulate ever greater economic power, and find ever more inventive ways to evade democratic restraint, they become more potent than many governments. There’s a word for this: oligarchy. Some of them use this power to demolish democratic safeguards. To give one example, they have lobbied successfully to pull down the rules and caps on campaign finance, until, in some nations, they appear to wield more influence over elections than the electorate.

…if we want to build the social and physical infrastructure we need to radically adapt to the realities of catastrophic climate change, we need to tax the rich!

I’m not looking for socialism here folks, just basic garden variety regulated capitalism!

There are 14 Billionaires in NZ + 3118 ultra-high net worth individuals, let’s start with them, then move onto the Banks, then the Property Speculators, the Climate Change polluters and big industry.

You should be angry, NZ Capitalism is a rigged trick for the rich and powerful. The real demarcation line of power in a western democracy is the 1% + their 9% enablers vs the 90% rest of us!

Do not allow their smears of ‘Envy’ dilute the righteous rage you should all be feeling!

There’s no point making workers pay more to rebuild our resilience, tax the rich!

-Sugar Tax

-Inheritance Tax

-Wealth Tax

-Financial Transactions Tax

-New top tax rate on people earning over $300 000 per year.

-Capital Gains Tax

-Windfall profit taxes

-First $20 000 tax free

Lift the tax yoke from the workers and the people and place it on the mega wealthy and have them pay their fair share for once!

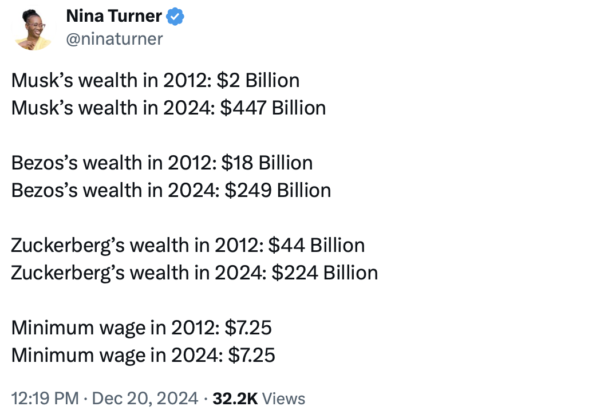

In 2010, the 388 richest individuals owned more wealth than half of the entire human population on Earth

By 2015, this number was reduced to only 62 individuals

In 2018, it was 42

In 2019, it was down to only 26 individuals who own more wealth than 3.8 billion people.

In 2021, 20 people own more than 50% of the entire planet.

In 2026 000.1% owned 3 times the wealth of the bottom 50%.

This isn’t democracy, this is a feudal plutocracy on a burning Earth

The Big Tech Tzars have manipulated our collective fear, ego, anger and insecurities through social media in a way that has led to the largest psychological civil war ever launched against one another.

We are but meat bags secreting hormones addicted to dopamine rewards for fat, sugar, salt and sex in a cultural landscape of individualism uber allas where we sing sweet secret lies to ourselves to make sense of a world around us that is frightening and in constant entropy.

Meanwhile, the planet burns and every aspect of our existence is monetarised for big data to sell us more stuff we can’t afford. We are alienated and anesthetized by a consumer culture that keeps us neurotic and disconnected. Our work, our existence, every move we make are all built to suck money to a minority class that sits above us while under neoliberalism, globalization, financialization, and automation, our existence as individuals has only become more disposable.