This article seeks to explain the extreme level of New Zealand’s deficiencies in managing its international obligations to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism.

The Start of International Efforts to Combat Terrorism Financing

Prior to the 9/11 attacks on US soil in 2001, there was no international coordinated effort to combat terrorism financing. Following the 9/11 attacks, that all changed.

Responsibility for co-ordinating an international approach to combat terrorism financing was assigned to the existing Financial Action Task Force (the FATF). The FATF was established in 1989 to co-ordinate an international approach to combat money laundering occurring through the international banking system. To achieve that purpose, FATF developed

40 Recommendations to guide countries on laws and systems for money laundering prevention.

Following the 9/11 attack, the FATF introduced 9 Special Recommendations. Known as FATF SR IX, the objectives of the international recommendations was to manage the internatoinal risks linked to terrorism financing.

FATF Special Recommendation VI (FATF SR VI) referred to the need for regulation and supervision of ‘alternative remittance systems’.

What are Alternative Remittance Systems?

Alternative Remittance Systems, also called Informal Value Transfer Systems, are methods of moving money or value outside of the formal or conventional banking system. These Informal or Alternative transfers are often used for convenience, lower costs in fees, and gaining access to regions without reliable banks. Often migrants from developing countries move to advanced economies and seek to send funds back to their families.

International remittance of funds from migrant workers have a legitimate purpose which is why the FATF President declared that it was important that in operation with national laws to combat terrorism financing, this does not extend to ‘Financial Exclusion’.

The FATF Special Recommendations to combat terrorism financing had the purpose of protecting the integrity of the global financial system. The FATF encouraged countries to modify their legislative and regulatory reach to extend to the alternative or ‘underground’ banking channels. By formalising the legitimacy of unconventional banking, there was more chance to detect terrorism financing and money laundering. Not regulating or turning a blind-eye to adequately regulate only increases domestic and international security risks.

For some countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia and the Canada, legislative systems cater to reporting from both conventional (wire transfer reporting) and unconventional reporting such as Hawala or Other Similar Service Provider, also known as HOSSP.

Whereas the above countries operate with prescribed transaction reporting that caters to both conventional (Wire Transfer) and unconventional (HOSSP), New Zealand’s AML/CFT Act limited international prescribed transaction reporting obligations to Wire Transfer only. This is set out at Section 5 of the AML/CFT Act where it states the definition of Prescribed Transaction Reporting is: prescribed transaction, in relation to a reporting entity, means a transaction conducted through the reporting entity in respect of— an international wire transfer of a value equal to or above the applicable threshold value; or a domestic physical cash transaction of a value equal to or above the applicable threshold value

It is this anomaly in New Zealand’s AML/CFT Act that is weakening New Zealand’s ability to demonstrate financial inclusion but also ability to monitor international activity outside of a wire transfer.

Not legislating for unconventional trading results in financial exclusion but this also increases risks to terrorism financing and money laundering. This is because transnational criminal groups look for the underground and unregulated banking channels that are unregulated.

Adequately legislating for Alternative Remittance Systems and prescribed transaction reporting for ‘unconventional’ trading (ie, not a Wire Transfer or ‘Electronic’ transfer), have a legitimate purpose but they must also be regulated.

Without regulation transnational criminals will exploit the weaknesses of that country?

What was the Purpose of FATF Special Recommendation VI?

FATF SR VI required countries to regulate persons and entities who provide services known as ‘informal money transfer systems’. FATF SR VI aimed to bring alternative remittance services under the same level of oversight as traditional (conventional) financial institutions, such as registered banks. By making these informal or alternative value transfers subject to the same level of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures, there was less opportunity for transnational criminals to operate anonymously.

In the interpretative note of FATF SR VI, it set out –

“Money or value transfer systems have shown themselves vulnerable to misuse for money laundering and terrorist financing purposes. The objective of Special Recommendation VI is to increase the transparency of payment flows by ensuring that jurisdictions impose consistent anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures on all forms of money/value transfer systems, particularly those traditionally operating outside the conventional financial sector and not currently subject to the FATF Recommendations. This Recommendation and Interpretative Note underscore the need to bring all money or value transfer services, whether formal or informal, within the ambit of certain minimum legal and regulatory requirements in accordance with the relevant FATF Recommendations.”

FATF Examines New Zealand’s Compliance to Combat Terrorism Financing

In 2003 and performing its role as the international watchdog to combat money laundering and terrorism financing, the FATF, jointly with the Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering, commenced a country inspection of New Zealand. The joint country inspection of New Zealand by these international oversight bodies have the purpose of examining NZ’s alignment against FATF’s Recommendations.

Following that country inspection and on 10 August 2005, the International Money Fund published a report of New Zealand’s position against the FATF Recommendations. For Special Recommendation VI (which relates to anti-money laundering requirements for alternative money value transfer services, the IMF noted that NZ did not have any licensing or regulatory requirement for these financial services. In particular, there was concern that New Zealand’s AML/CFT regime did not explicitly cover informal remittance providers (like hawala) under its existing laws. The IMF report also highlighted risk-management issues, pointing out that some of these value-transfer systems could be used for terrorism financing, and thus, NZ needed to have robust oversight.

In summary, the IMF believed NewZealand’s compliance with Special RecVI was weak in 2005 due to gaps in regulation of informal remittance systems. The IMF called for New Zealand to have stronger legal and supervisory measures.

Fast Forward Six Years

In 2009, the FATF carried out a further country examination of New Zealand. At this time New Zealand was inspected between 20 April 2009 to 1 May 2009. During this ‘on-site’ country inspection, the FATF evaluation team met with officials and representatives of relevant New Zealand government agencies and the private sector.

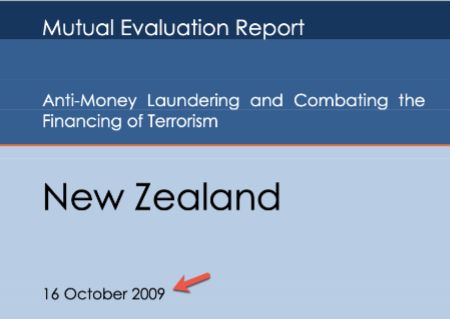

On 16 October 2009, FATF published its report of the country inspection of New Zealand (FATF 2009 NZ Report). The following statements have been extracted from the FATF 2009 NZ Report:

At paragraph 69:

“The alternative remittance and underground banking sectors are also potential avenues through which the proceeds of crime can be laundered and that provide added anonymity since the sector is by nature unregulated and largely invisible.”

At paragraph 91:

“Although the sector in New Zealand is dominated by a single provider, Western Union, many of the Western Union franchises and outlets are based in local businesses, such as dairies (corner stores) and post shops. There is also evidence of an unknown number of informal providers, at least some of which probably operate a hawala-style remittance system.”

At paragraph 638:

“The exact number of MVTS providers doing business in New Zealand is unknown –although discussions during the on-site visit suggest that the sector is quite diverse. The absence of a supervisory framework in this sector makes it relatively easy for informal channels of remittance services to operate. It should also be noted that there is evidence that an unknown number of informal providers, at least some probably operating a hawala-style remittance system, operate in New Zealand.”

“… as the MVTS sector is currently not subject to supervision, it cannot be said that the New Zealand authorities have taken sufficient action to make MVTS providers, including operators of informal remittance channels, subject to AML/CFT requirements.”

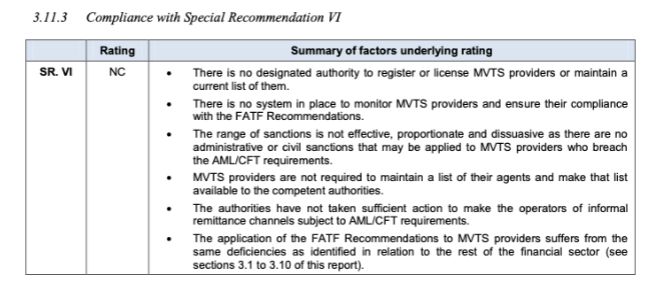

In concluding recommendations and comments on New Zealand’s performance against FATF SRVI, the report noted at page 130:

“New Zealand should designate a competent authority or authorities to register and license MVTS providers (both natural and legal persons), monitor compliance with the registration and licensing requirements, maintain a list of current MVTS providers and ensure compliance with the FATF Recommendations.”

“MVTS providers should be required to maintain a current list of their agents and this list should be made available to competent authorities.”

“The authorities should take action to identify informal remittance channels and make these operators subject to AML/CFT requirements.”

The overall finding in FATF’s 2009 Report to New Zealand’s compliance with the principles of FATF SRVI was “NON-COMPLIANT”. An extract of that finding is set out below:

NZ Attempts To Meet FATF SR VI – And Fails – Again!

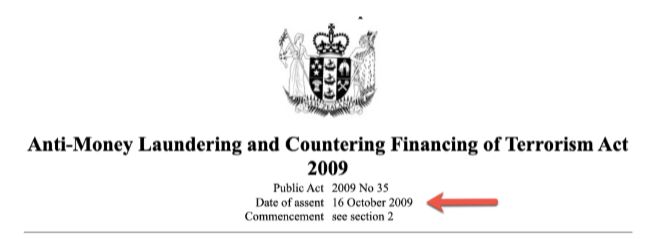

It is important to note that the FATF 2009 Report was dated 16 October 2009 (see figure 1 below) which was the same day that the NZ AML/CFT Act 2009 received its Royal Assent (see figure 2 below).

Figure 1 – FATF MER Report Cover:

Figure 2 – NZ Royal Assent:

The relevancy of the above two dates is that it can be assumed that if the FATF Report of Non-Compliance and urgent recommendations is dated 16 October 2009, which is the same date as NZ’s AML/CFT Act transitioning into ‘assent’, then it would not be possible for the FATF Mutual Evaluation Report and urgent recommendations to be implemented into NZ with the passing of the AML/CFT Act.

Given that October 2009 was 8 years following the 9/11 attack on the United States of America, how can New Zealand be certain it was not a conduit country of that terrible event – like any terrorism act is.

The purpose of having international standards is to have a universal co-ordinated approach. A weak link in the chain does not serve international security interests well when the weak link is in the universal chain to combat money laundering and financing of terrorism.

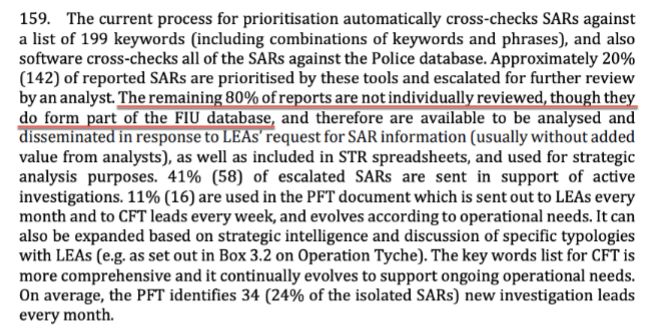

This is why it was distressing to read in New Zealand’s FATF Mutual Evaluation Report 2021 (FATF NZ MER 2021) that the NZ Police FIU are only examining 20% of Suspicious Activity Reports that New Zealand’s business community is sending to the NZ Police FIU on concerns and reporting suspicions of terrorism financing or money laundering. Paragraph 159 (figure 3 below) of the FATF NZ MER 2021 is extracted and copied below. The paragraph is referring to Suspicious Activity Reports that the business community submit to the NZ Police FIU and confirms that 80% of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) are not individually reviewed:

Figure 3: FATF 2021 MER NZ (para 159)

It would seem from the FATF findings and reporting in paragraph 159 of their Mutual Evaluation Report that New Zealand’s best efforts in investment in managing threats arising from transnational crime, financing of terrorism, corruption, serious fraud, child trafficking, human trafficking, arms trafficking etc – is to use ‘key word searches’ on a spreadsheet against ‘wanted’ or ‘targeted’ individuals.

New Zealand Snubs Its Nose To Real International Problems

When examining New Zealand’s history of non-performance against international standards, with links to combatting transnational crime, serious fraud corruption etc – it is clearly demonstrated that NZ has not been well governed to combat simple issues as financial crime – and it continues that way today.

International reports and results from Official Information Act requests are confirming that New Zealand has failed to appreciate the risks linked to drug trafficking and money laundering. This was the reason the 1989 G7 summit elected to bring into ‘westernised banking systems’ a universal approach to international banking. They were urgently reacting to the increasing international security threats arising from drug trafficking and money laundering through the international banking system.

New Zealand’s history would appear to demonstrate that New Zealand, or at least its decision-making powers responsible for combating serious fraud, transnational crime and corruption etc – are yet to attend the 101 Combat Financial Crime course.

Sticking a few band aids on legislation that has a weeping and festered wound will not make the problem go away. And nor can this problem be swept under New Zealand’s long sweeping carpet. New Zealand’s recent Royal Commission of Inquiry’s have proven that method doesn’t work. History and wrong doing of the past always surfaces in the future.

New Zealand has always been an inherently high risk country to being a conduit country to money laundering and financing of terrorism. This is because of its geographic location and strong political ties to the Pacific Islands. New Zealand is grotesquely at high inherent risk to facilitating money laundering, financing of terrorism, corruption and serious fraud and accordingly, controls must be in place to manage, monitor and report.

This was the warning that the G7 Summit gave at the 1989 meeting in Paris. At paragraph 52 of their published Economic Declaration, the G7 leaders declared:

“The drug problem has reached devastating proportions. We stress the urgent need for decisive action, both on a national and an international basis. We urge all countries, especially those where drug production, trading and consumption are large, to join our efforts to counter drug production, to reduce demand, and to carry forward the fight against drug trafficking itself and the laundering of its proceeds.”

Fast Forward to 2025

Once again the public will be irritated by all the song and dance arising from New Zealand politicians jumping on the political bandwagon to sing their praises of how they intend to combat transnational crime, serious fraud, money laundering etc.

A band-aid approach would be to pass a law to ban the wearing of ‘colours’ which subsequently clogs the already broken NZ court system with an astronomical number of defended cases. That is a significant cost to the NZ tax payer and it does nothing to lessen transnational crime, corruption and serious fraud.

Spending Tax Payers Funds Wisely Should Be Compulsory in Combating Crime

Instead of tax-payers funds to stop some colours being worn by some people in society would have been better destined for expenditure on areas where it can guarantee a reducing in transnational crime.

This powerful tool is called AML/CFT Supervisory Technology or Fin-Crime Technology – basic tools to do basic things to combat financial crime. This was the purpose of the AML/CFT Act but it would appear, NZ is still using spread-sheets and no AML/CFT Supervisory Technology.

This is why New Zealand will continue operating two-steps forward and three-steps back when it comes to making the right choices to fight real problems for all New Zealanders.

Failure to adequately regulate to combat financial crime means failure to govern.

Let’s see what magic NZ Politicians will throw at New Zealanders over the next year as they promise to once again “get tough on crime”.