Hi. Yesterday I hit you with eleven pages. Here’s an AI summary.

The Illusion of Prudence

For nearly forty years, New Zealanders have been told that fiscal responsibility keeps us safe.

But the truth is the opposite. It’s not responsible, and it’s making us poor.

Under the Public Finance Act (1989) and the Fiscal Responsibility Act (1994), our governments are prohibited from directly funding themselves through sovereign credit creation.

Instead, they must borrow our own dollars from commercial banks — at interest — even though those same banks were licensed by us to create those dollars in the first place.

That’s not prudence. That’s servitude.

A dollar of sovereign credit, issued debt-free by the state, is a national asset. It mobilises people and resources for production without compounding debt. Yet instead of using that sovereign power, we borrow from “financial markets” — selling bonds to private banks and investors, many of them offshore.

This is not responsible finance.

It is a racket — a form of financial colonialism that pays rent to private money-creators while starving public investment.

The Fiscal Trap in Action

When the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) later buys back those government bonds — as it did during the COVID crisis — it simply creates new money (“reserves”) out of nothing and pays the banks full value for the bonds.

Those reserves, which the RBNZ itself created, then earn interest at the Official Cash Rate (OCR) — currently around 5.5%.

That means taxpayers are literally paying rent on money the state created.

“Reserves are remunerated at the OCR, creating a cost for the Bank when the OCR rises.”

— RBNZ: Monetary Policy Tools and the Balance Sheet (2021)

In substance, the state is paying tribute to private money creation — a system designed not to serve the nation, but to guarantee risk-free returns to financial intermediaries.

The Result: A Debt Machine That Extracts Wealth

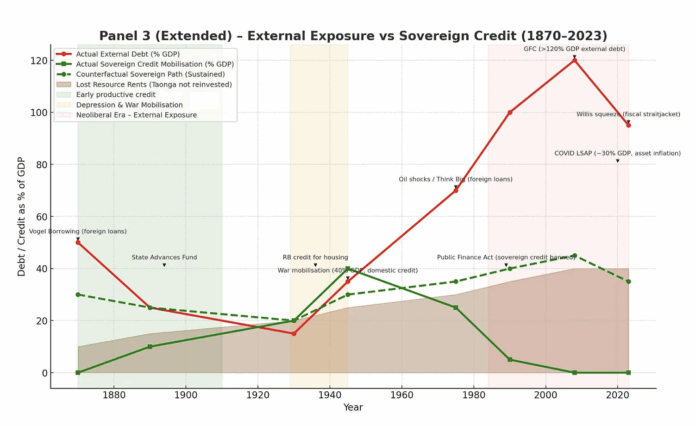

The so-called “prudence” of Rogernomics and “Ruthanasia” has turned New Zealand into a rentier colony of its own banking system.

We are bleeding national wealth through interest, dividends, and offshore profit repatriation — every year, without fail.

Total annual leakage: $25–40 billion — around 8–12% of GDP.

That’s equivalent to every household in New Zealand losing $15,000–$20,000 per yearin potential disposable income or public benefit.

That’s the cost of obeying (serving) “the markets.”

The Mechanism of Servitude

- Treasury issues bonds to private markets.

- Banks create credit to buy them — new money conjured on their balance sheets.

- The RBNZ later buys those same bonds with reserves it creates from nothing.

- Banks then earn OCR interest on those reserves.

- Taxpayers cover the difference between low-coupon bonds and high reserve rates.

It looks clean on a spreadsheet.

But in reality, it’s a tribute system — a transfer of wealth from citizens to financiers.

Even the Parliamentary Library confirms that the RBNZ bought bonds using “settlement cash balances it created,” while the Crown indemnified any losses.

Banks made at least $3 billion from that transaction alone in the Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP).

Not bad — for them. But it did not serve our economy in any meaningful sense beyond simply keeping it alive at the cost of billions of pounds of flesh.

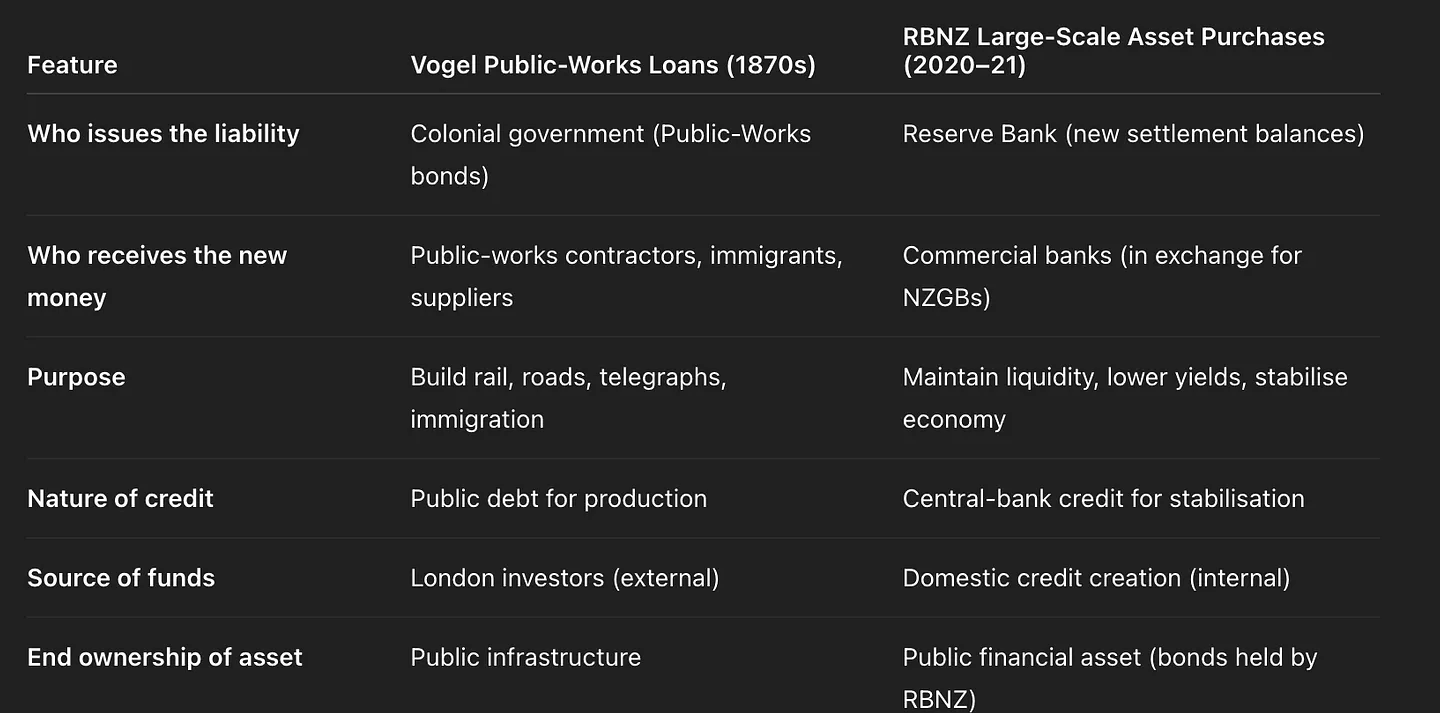

In both cases, the state expanded its balance sheet to direct resources.

Vogel imported capital through bonds; the RBNZ created capital through reserves.

The difference is where the credit came from: external then, internal now.

Why the LSAP qualifies as public credit in form, but not in benefit

The LSAP created roughly $53 billion of new settlement cash “out of nothing.”

That is sovereign credit in a technical sense: the state created purchasing power.

However, it did not use that power to finance productive activity directly.

Instead, the RBNZ used it to buy existing government bonds from private holders—mainly banks and funds—who then earned the OCR on the new reserves.

So the flow of benefit went to the financial sector, not to public investment.

Hence:

The LSAP proves that the government can create money on command —

but it also proves that our current framework channels that power into rent, not renewal.

The Political Illusion

The Fiscal Responsibility Act doesn’t restrain borrowing; it restrains imagination.

It demands that governments “reassure creditors,” making obedience look like discipline.

As the NZ Institute of Economic Research observed in 2018, it is a “weak, non-binding policy that nonetheless altered political norms.”

Translation: politicians fear the bond market more than they trust their own people.

Yet the bond market lusts after our sovereign debt precisely because it is risk-free.

A sovereign currency issuer cannot go bankrupt in its own currency.

So why pretend otherwise?

The Alternative is Sovereign Credit and National Development

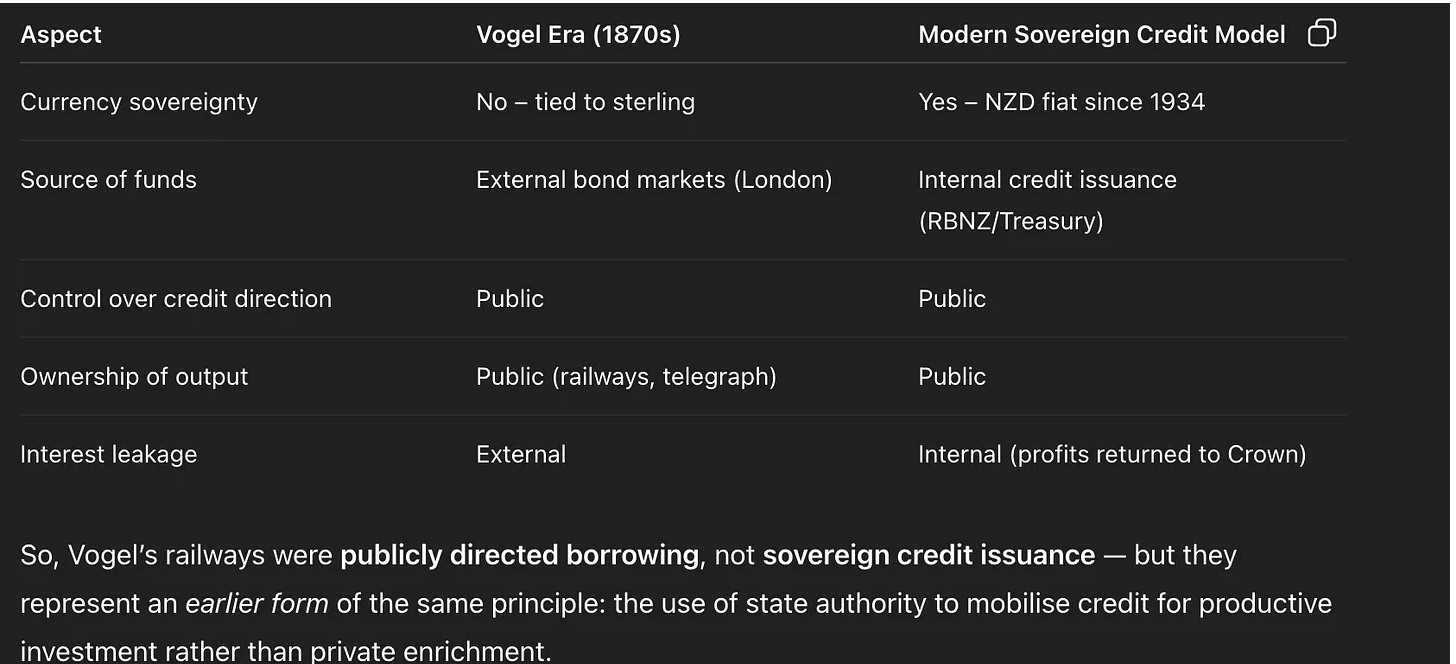

The idea of using public authority to mobilise capital is not new in New Zealand. Every great period of New Zealand nation-building — the Vogel railways, hydro dams, and post-war housing programme — was financed through public credit, not private debt.

In the 1870s, Julius Vogel’s Public Works and Immigration Policy raised about £10 million on the London markets to build the railways, telegraphs, ports, and settlements that knitted the young colony together.

Technically, Vogel borrowed abroad because the colony lacked a sovereign currency and domestic capital markets. But the principle was unmistakably public-credit in spirit: the state directed credit for productive nation-building. The bonds were issued by the government, the funds allocated to infrastructure, and the resulting assets remained in public ownership.

Vogel’s system therefore demonstrated a truth that later generations forgot — that credit, when steered by public purpose, can transform a nation’s productive base.

Fast-forward a century and a half, and we see the same power used in reverse.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s Large-Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme created roughly $53 billion of new settlement cash “out of nothing” to buy existing government bonds from private investors. That was, in every technical sense, sovereign money creation: the central bank expanded its balance sheet and issued credit backed only by the Crown.

Yet unlike Vogel’s loans, the LSAP did not finance railways, housing, or industry.

It financed liquidity. The new money went to commercial banks and funds, who then earned interest on those reserves at the Official Cash Rate (OCR). The result was public credit turned inward — sovereign creation without sovereign purpose.

We can do this again, using the tools we already control.

Three key reforms can break the trap:

- Create a National Development Bank — publicly owned, lending at cost for housing, energy, rail, and food security.

- Coordinate Treasury and the RBNZ — permit direct issuance of sovereign credit for infrastructure, with profits remitted to the Crown.

- Redefine “prudence” — as productive investment that strengthens the nation, not obedience to foreign creditors.

This is how Japan rebuilt after 1945, how Norway built its sovereign wealth fund, and how Singapore became debt-light but capital-rich.

The Economic Reality of Reform

Reclaiming even half of today’s $25–40 billion leakage would:

- Fund 100,000 affordable homes or complete a national electrified rail systemevery decade.

- Cut external deficits by 3–5% of GDP.

- Keep profits circulating locally, boosting wages, innovation, and resilience.

- Stabilise the NZ dollar by reducing offshore debt dependency.

- Lower household interest burdens through low-cost, publicly financed mortgages.

This is not inflationary if managed transparently and tied to real productive capacity.

As Professor Richard Werner explains:

“It is not money creation that causes inflation, but misuse of it.”

— Princes of the Yen (2003)

The Moral Principle

Sovereign credit should build public wealth — not provide private rents.

We can keep the good features of our current framework — honesty, transparency, accountability — while redirecting them toward national prosperity rather than financial servitude.

This means:

- Reforming the Public Finance Act.

- Replacing the Fiscal Responsibility Act with a National Investment Charter.

- Establishing a Development Bank and a direct RBNZ–Treasury credit channel.

Because New Zealanders should never have to beg for the money we already create.

The National Choice

We can afford anything we can build.

What we cannot afford is another generation of debt servitude disguised as discipline.

It’s time to end the fiscal illusion — to stop paying rent for our own money — and to start rebuilding the productive, sovereign, and prosperous nation we once were.

Sources / Further Reading

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand — Monetary Policy Tools and the Balance Sheet (2021)

- Parliamentary Library — Research Brief: LSAP Programme (2021)

- Treasury — Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand (2024)

- Stats NZ — Balance of Payments: Primary Income Outflows (2024)

- NZIER — Discussion Paper on Fiscal Responsibility (2018)

- IMF — Fiscal Rules Database (2025)

- Werner, Richard — Princes of the Yen (2003)

- Hudson, Michael — Killing the Host (2015)

Tadhg Stopford is a historian and teacher.

Support change by purchasing your CBD hemp CBG at www.tigerdrops.co.nz

It would be interesting to know, from someone who understands these things better than I do, about the differences and similarities between your sovereign credit idea and the social credit espoused by Bruce Beetham a few decades ago.

‘Social credit espoused by Bruce Beetham a few decades ago.’

It was also known as ‘Credit Reform’ as espoused by members of the First Labour Government(notably the rebel John.A.Lee).

Most importantly it was used successfully to finance New Zealand’s Second World War costs. This country did NOT borrow money to pay for its war industries.

Guaranteed markets for our agricultural exports helped and there was heavy government regulation on land and commodity prices. There was inflation but not nearly as severe as critics predicted.

Have a look at:

Briggs, Phil. Looking at the numbers: a view of New Zealand’s economic history. Wellington: New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, 2003.

Condliffe, J. B. New Zealand in the making: a study of economic and social development. 2nd ed. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1959.

Hawke, G. R. The making of New Zealand: an economic history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Beetham emerged as SC party leader in the late seventies, at a time when interest rates were at double digit figures. He proposed setting up an publicly owned monetary creation institute which would lend money, created by fiat, to the banks at 7%; for what purpose I’m not sure. Social Credit policy generally advocated lending fiat money at zero%, or at a rate just sufficient to cover lending costs.

SC’s original proposals entailed depriving banks of the right to create money by fiat, though I don’t recall whether this whether this was also the case with Beetham.

John A Lee called his methods “Social Credit” and sought to distinguish them from the SC party’s policies, which he labeled “Douglas Credit” – its main promoter world wide was a certain Clifford Douglas – probably because he did not wish for their “bad reputation” with regard to monetary policy to rub off on him, though I don’t think his ideas were any different from Douglas’s. Mind you, Douglas, and I think Beetham, advocated what we would now call a UBI and perhaps Lee did not wish to be associated with that sort of policy.

Prior to 1954 followers of Clifford Douglas pursued his ideas within the Labour Party, but broke away to form their own party when it became clear that their ideas were making no impact within Labour. I think this was a mistake since, as a small party outside the mainstream, they had no chance of gaining enough seats, if any, to make an impact within parliament. I think those still following Douglas should now rejoin Labour and pursue his ideas on the floors of conference: MMT and UBI ideas these days have become more respectable, I think, than they were in Beetham’s time.

It’s just common sense really! Great post thankyou Tadhg Stopford.

Comments are closed.