GUEST BLOG: Ian Powell – Heart health care system “verge of collapse” a barometer of wider public hospital verging

It has been said more than once that overcrowding in emergency departments is a barometer of how public hospitals as a whole are performing in Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system.

It has now emerged that another barometer is the rate of heart attack patients being treated within clinically accepted timeframes.

According to a new Otago University report, Heart disease in Aotearoa: morbidity, mortality and service delivery, commissioned by cardiac advocacy charity Kia Manawanui Trust (the Trust), the rate of these patients not being treated within clinically appropriate timeframes is a massive one-half.

While dramatic, this is not as surprising as one might think. New Zealand has just one-third the number of cardiologists it needs. It has led to the regrettably correct conclusion that the heart healthcare system is verging on collapse.

Health journalists doing their job

Another piece of thorough reporting of a health scandal by Ruth Hill

This scandal was well reported on 11 August by Radio New Zealand’s health reporter Ruth Hill: Half of heart attack patients not treated within accepted timeframes.

She quotes the Trust’s Chief Executive Letitia Harding in a dramatic, but not overstating, manner observing that the findings exposed a system that was failing at every level. In her words:

Heart care in New Zealand isn’t just stretched – it’s on the verge of collapse. We are failing in all aspects and it’s costing New Zealanders their lives.

TVNZ gave the report prominent coverage on 1News (11 August): Verge of collapse.

Stuff’s Nicholas Jones also provided extensive coverage

Stuff journalist Nicholas Jones, like Ruth Hill, on the same day also gave a good outline of the report’s findings: People are dying.

Key Findings

The reports key findings include:

- Life-threatening delays: Half of all heart-attack patients are not seen within internationally accepted timeframes.

- New Zealand has only a third of the cardiologists it should have.

- Māori and Pacific people hospitalised or die from heart disease more than a decade earlier, on average, than other New Zealanders.

- Heart disease costs the country’s health system and economy $13.8 billion per year ($13 million in 2020). The biggest contributor is hospitalisations but also contributing are lost workdays, GP visits, prescriptions and mortality. [These are minimum costs as some other factors such as emergency department admission costs were not included in this analysis.]

- Regions with the highest death rates are Tairāwhitii, Lakes (Rotorua-Taupo), Whanganui, and Taranaki. They have the fewest cardiac specialists.

Dr Sarah Fairley is a Wellington-based cardiologist. She is also the Trust’s medical director. Her conclusion was that the findings by the Otago University study matched the experience of health professionals on the cardiac frontline.

Cardiac workforce reality check

Sometimes non-government organisations can be overly gentle and deferential in describing bad news such as this. However, the Trust does not pull its punches over the report’s findings. It calls a spade a spade.

This in the context of heart disease being the greatest cause of mortalities in New Zealand. It was responsible for one in five deaths and 5% of hospital admissions.

The Trust is calling for immediate investment in public hospital cardiac care infrastructure – beds and equipment – and a national strategy to recruit and retain cardiology staff. This goes to the root of the “verging collapse”.

Drilling down further, in 2024 New Zealand had 173.2 full-time cardiologists (32.8 per million people). This is three times lower than the average (95 specialists per million) of all countries measured by the European Society of Cardiology. Contrasting the figures 32.8 and 95.0 speaks volumes.

However, the cardiac workforce is not just medical specialists. The number of sonographers had dropped from 70.4 in 2013 to just 43.5 in 2024, despite the 17% population increase. Their ratio had nearly halved from 16 per million to 8.2 over the same period of time.

Political reaction

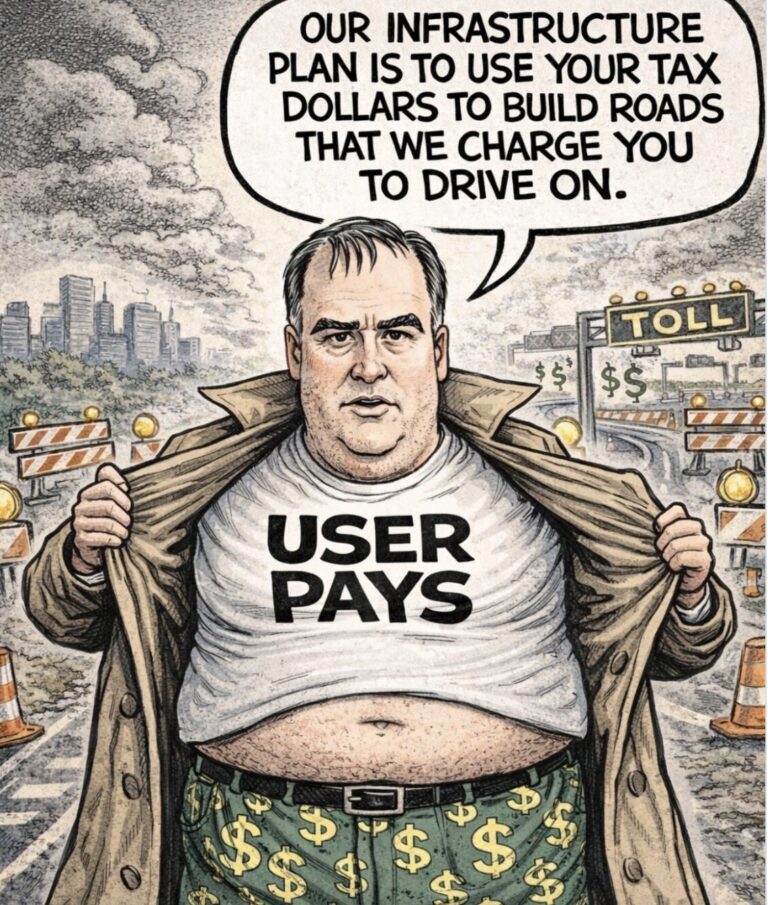

Health Minister Simeon Brown in response gave some acknowledgement to the report but passed the buck to Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora) as if its political leadership were not responsible in some way.

Simeon Brown acknowledges report findings but downplays ‘verging collapse’

He referred to it establishing a National Clinical Cardiac Network which is developing national standards and models of care. In fact, this network was established well over a decade ago when Tony Ryall was health minister (2008-14).

The network did good innovative and collaborative work. But the vertical centralisation of the health system under Labour’s Andrew Little meant that the network was brought under direct bureaucratic control thereby giving it less oxygen for its independent advice.

A further dimension: clinical follow-ups

Understandably the impression can be formed that the critical threshold for treatment is to have a first specialist assessment (FSA).

In this context this is the assessment by a cardiologist of a patient’s heart condition following a general practitioner referral for further investigation.

Where, for whatever reason, treatment such as surgery was not consequentially scheduled after the FSA (including because further monitoring was considered more appropriate) a clinical follow-up would normally be scheduled within a clinically appropriate timeframe.

In the mid to late 2010s, towards the end of my employment as Executive Director of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists, I became aware of increasingly serious concerns of a range of medical specialists (not just cardiac) that these clinical follow-ups were being severely delayed

As a result, their patients (including children) were facing increased health risks. This includes denial through excessive delay of access to treatment that might have improved these conditions. This was regardless of location – rural, regional or urban.

Consequently, the powerful message given by Northland cardiologist and Trust Board member Dr Marcus Lee on Radio New Zealand’s Midday Report (11 August) in an interview with Charlotte Cook, resonated strongly with me: Delayed clinical follow-ups.

After pushing back on Minister Brown’s use of statistics, Dr Lee referred to the downside negative effects on clinical follow-ups after patients’ FSAs.

The cause of these clinically unsafe delays is the sheer volume of FSAs which had to take priority. Coupled with severe workforce shortages, these patients were trapped in a vice.

Consequently, for many, their health conditions worsened to the extent that those who might otherwise have been able to be treated could not be. In other words, they were denied access to necessary diagnosis and treatment.

Moral injury

Dr Lee also raised the issue of moral injury. In the context of healthcare it refers to the psychological, social and spiritual impact of events on health professionals who overwhelming hold strong ethical values over, for example, denial of timely access of patients to diagnosis and treatment.

This includes when events are determined by factors beyond their control, particularly political (especially) and bureaucratic decision-making.

In the context of Dr Lee’s reference to moral injury it is the cardiologist that has to explain this situation to patients and families of the harm done by delayed diagnostic or treatment access even though it was not caused by him or his colleagues.

Although responsibility rests with political and bureaucratic decision-makers they are not the ones who have to explain it to harmed patients and their families. Dr Lee made the point well that one consequence is the undermining of patient trust in him and his colleagues.

The heart healthcare barometer and a “wake up” call

A standout observation by the above-mentioned cardiologist Dr Sarah Fairley really struck home with me. In her words:

From inside the system, I can tell you that this report reflects what we see every day – a workforce stretched beyond safe limits, patients slipping through the cracks and no end in sight.

Health system pleads for help (Parton, NZ Herald}

While this comment was made in the context of the heart healthcare system, it also reads as a standalone comment for the whole public health system, regardless of branch of medicine or type of diagnosis and treatment.

The verging collapse of the cardiac care system is a barometer of the public hospital system as a whole. Public hospitals across the health system are in all in this dire situation with differences being in degree, not kind.

One only needs to read the latest travesty involving adult inpatient and related mental health services in Canterbury due to ineffective governance, understaffing and cumulative strain for a decade.

This disaster was covered by Nadine Roberts in Stuff (12 August): Damming mental health report.

Christopher Luxon’s government hasn’t caused the “verging collapse”, but it is contributing to it

Christopher Luxon’s government can’t be blamed for Aotearoa’s deteriorating health system. While it has worsened under his watch, it is an inherited state of affairs.

It goes back to the relative underfunding (‘light austerity’) of the National led government for much of the 2010s and the poor compounding health system stewardship of under the previous Labour led government whose solution was destructive restructuring through vertical centralisation.

What characterised all three of these governments is their shared neglect of the severe medical specialist shortages that first became evident in the late 2000s.

The last word should be left to the Trust’s Chief Executive Letitia Harding. She said that the report should be “a wake-up call for the government”.

She nailed it in one. But it is equally a wake-up call for the government for the whole health system.

Ian Powell was Executive Director of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists, the professional union representing senior doctors and dentists in New Zealand, for over 30 years, until December 2019. He is now a health systems, labour market, and political commentator living in the small river estuary community of Otaihanga (the place by the tide). First published at Otaihanga Second Opinion

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/companies/healthcare/health-nz-board-costs-could-triple-amid-deficit-and-staffing-woes/ETVXHDFQYRA6PPD6UHJKFCD7VY/

Fiscally responsible my arse. This government is shit!

Why the fuck did they put a boy in control of health whose only qualification was that of a bank teller.

Australia is looking better and better by the day.

You say Christoher luxone can’t be blamed but he promised us he would get our country back on track. And Simeon has said we would get timely quality healthcare whenever we needed it regardless of what they are or where we live and he went on to say our government is committed to delivering better health outcomes so all kiwis can live longer healthier lives. These are his words now you wonder why so many Kiwis are pissed off and want to get rid of them. My elderly mother was stuck in A and E for 16 hours my sisters had to fight for her to get admitted onto a ward @ Waikato hospital, she was stuck in a cubical. My sister said all the young people who needed to were admitted but not our 83yr old mother as she had multiple things wrong, its like they don’t care if your old. Now we don’t blame the staff we know they are doing there best we blame the government as the health system is in a shambles. Simeon the parrot needs to stop talking with a forked tongue

I support the efforts to increase the capability of our public health system, although since heart disease is often lifestyle-related, I don’t understand why we ignore the cause of the problem. This government even supports the industries that sell products that cause the problem so I don’t see any immediate improvement.