Ever since Thomas Coughlan was made the Political Editor of the NZ Herald, he has been writing some of the best, most insightful and ideologically understanding of the factions involved of any mainstream media journalist in the game right now.

He is quickly becoming a must read Fourth Estate Journalist.

Don’t get me wrong, he was always good, but since taking on the Political Editorship, has branched out into a level of oversight that is very intelligent while also being incredibly insightful.

He is a reason to subscribe to the NZ Herald right now.

A piece he wrote recently is a prime example…

Inside the climate debate that quietly rocked the National Party

THREE KEY FACTS

-

- The Government set New Zealand’s 2035 NDC – a climate change target – in January.

- The target is to reduce emissions from 2005 levels by 51% to 55%.

- On current forecasts, hitting the 2030 NDC will require the purchase of offshore abatements.

…Coughlan details the reality of dark agriculture money that drives the reactionary protests with culture war triggers from the Taxpayers’ Union talking points and how that impacts the actual policy.

The truth is that the marketisation of carbon credits is a fantasy that doesn’t offset any fucking thing.

It’s a vast scam, it always has been…

In the United States from the 1960s, pollution market proposals failed to materialise. Eventually, within the 1990 US Clean Air Act 263, coal, oil and gas-powered industry installations joined a sulphur dioxide permit trading scheme. A 29% emissions reduction for the following decade was less than the 60% achieved by comparable EU installations then subject to state regulation. Even the US decline was attributable to the Clean Air Act; the actual purpose of the emissions trading initiative was to”merely to try and make the regulated reductions cheaper for the polluting industries”.

Us economists nevertheless framed their sulphur emission reductions as a vindication of the price mechanism. At the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, International decision-making on carbon emission s and global warming mitigation was inaugurated by the UNFCCC. Under this rubric, the international Energy Agency and the OECD tasked an expert group to seta. greenhouse gas trading scheme for industrialised nations. Meanwhile, US Government advisors established a carbon trading negotiations framework for the Kyoto UNFCCC meeting in December 1997. AT this Conference of the Parties (COP), Al Gore’s delegation rejected arguments for a taxation-regulation approach to carbon emission reduction and forced through a market-based trading schema. Although President George W Bush later withdrew from the protocol in March 2021, the ideological commitment forged at Kyoto was pivotal. By this time the IPCC founded in 1989 had collated strong scientific evidence that growing carbon emissions were increasing global warming. Firming scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change informed the first ever international gathering requiring countries to reduce carbon and other greenhouse gas emission. At the time, and even more in retrospect, COP3 represented a critical conjecture. Kyoto delegates were not simply dealing with a major configurable problem; fossil-based capital accumulation was destabilising the Earth system and life forms therein.

Within this surrounding totality, the Kyoto Protocol facilitated international, supranational, national, regional and inter-city architectures for carbon trading. Initially the Clean Air Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI), as distinct UN governing bodies, designed projects likely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and advance renewable energy projects. The former body (CDM) covers countries without Kyoto-established emission targets. Joint Implementation carbon credits were available for countries with set Kyoto targets in the EU, North America and ex-Soviet Union alongside Japan. Carbon markets researcher Gareth Bryant has pointed out that specifiable reductions were a measure of “the difference between actual greenhouse gas emissions and a baseline scenario of what would have occurred in the absence of the project”. Such differences were rendered commensurable by carbon credits. Certified emission reductions for the CDM and the emissions reduction units for the JI could be sold to governments and, eventually, individual companies.

Obtaining and surrendering carbon verist on a counterfactual basis became an alternative to reducing carbon emissions at the source. The Kyoto Protocol , involving 193 countries, required governments of developed nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 5.2% below 1990 levels by 2012. Yet for the dame period, IPCC advice to its parent body (UNFCCC) called for 60%-80% cuts in carbon emissions at source. Controversially, the Kyoto Portico also identified six measurable and comparable greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbons and petrol fluorocarbons. In carbon markets, they were deemed as qualitatively equivalent, fungible and tradable units despite their different heat-trapping properties in the atmosphere over time. Growing integration between the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) and CDM drove carbon trades worth billions of dollars, involving thousands of industrial projects across supranational, national and subnational jurisdictions. Alongside the UN-administered CDM process, a voluntary offset market enabled developed countries and major corporates to meet emission reduction targets by providing investment assistance to developing countries anting to construct low and non-carbon projects. Such schemes were set within regulations beyond UNFCCC purview. Carbon markets themselves were, in part, extensions of global capitalism. The IETA, for example, representing 176 transnational financial, legal, energy and manufacturing corporations profited from the banking and borrowing of carbon credits, financial intermediation in carbon markets, plus the lobbying of government regulators for pollution rights. Major purchase of UNFCCC carbon credits included Barclays Capital, Deutsche Bank, BNP Paibas Fortis, Kommunal Kredit, Sumitomo Bank and Goldman Sachs.

After rapid expansion of overlapping emissions markets from 2005 to 2008, collapsing carbon prices and fragmenting carbon markets slowed the development of emissions savings projects. Oversupply of emission allowances devalued carbon credits and reduced investor interest in the CDM. From 2008 to 2011 inclusive, credits generated by new CDM projects declined year on year. In 2012, political economists Steffan Bohm, Anna-Maria Murtola and Sverre Spoelstra, in a climate issue anthology, declared, editorially, that the Copenhagen, Cancun and Durban COPs for 2009, 2010 and 2011, respectively, were “tremendous failures in terms of their inability to agree to a new post-Kyoto emissions reduction regime”.

At Durban, participants, especially from the EU, proposed a carbon crediting and trading initiative involving internationally, competing installations from multiple economic sectors including steel, cement, lime, pulp and paper, aluminium, plus upstream oil and gas production (flaring, venting). Mooted bilateral and unilateral market mechanisms would allow countries to assemble, jointly or individually, their own trading regimes and count the results towards global targets. Also discussed were new carbon offset mechanisms and projects for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). After the Durban Conference, admisdt collapsing carbon prices, climate finance researcher Reyes concluded that “the creation of new market mechanisms would simply exacerbate the problem of an overproduction of emissions allowances”. This process would also reproduce the tendency whereby “offsetting increases rather than reduces greenhouse gas emissions”. Climate justice networks were similarly sceptical. Already the April 2010 Cochabamba World Peoples Conference on Climate Change had proposed the decommission of carbon markets, including the ETS. In February 2013, over 130 environmental and economic justice groups signed a declaration entitled “It is Time to Scrap the ETS!”

Major corporates, however, were committed to carbon pricing as the essential remedy for mitigating anthropogenic climate change. In September 2014, a World Bank group statement signed by 76 countries, 23 subnational regions and over 1000 companies and investors urged government leaders to price carbon, an initiative timed to coincide with the UN Secretary General’s International Climate Summit in New York. Over 120 state leaders attended alongside representatives from business, civil society and universities. The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris revealed a central incompatibility between diagnosis and prescription. All parties acknowledged the scientific consensus: anthropogenic climate change was extant and irremediable without substantial countermeasures. Protocols signed by 196 countries agreed to hold global average temperature increases under 2% and to pursue a 1.5% limit. A 5-yearly international stocktaking of emissions performance would begin in 2023. But to meet Paris Agreement targets, parties continued to follow market-based approaches, not direct regulation. Under a Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) scheme, individual countries would voluntarily determine their emission mitigation targets subject to regular disclosure and review. Without an overarching carbon market architecture or governance structure, diverse approaches to mitigation accounting proliferated. Meanwhile, many corporates engaged in carbon-greenhouse gas emission credit markets and offset markets. During 2020, Nicolas Kreibich and Lukas Hermwille surveyed 482 large companies involved in balancing carbon-greenhouse gas emissions against carbon sink absorptions through carbon credit trading. Out of their sample, 216 companies with combined annual revenue of over US$7.5 trillion were participants in carbon offset markets for oil, chemical, steel, aviation and dairy companies plus others with high carbon/greenhouse gas emission levels. Such markets were perceived by companies as the only viable means for reaching carbon neutrality. Kreibich and Hermwille expressed “significant doubt” that such targets could be met.

Clearly, carbon credit and offset markets were, and are, unaligned to the broad concerns and goals of the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, companies and governments hoping to meet emissions reduction targets were not legally obliged tho do so. Such anomalies drew more scathing assessments. For James Hansen, Paris temperature reduction goals were fraudulent. Global gatherings of this kind were pointless without volume-based taxes on greenhouse gas emitters. Similarly, economist and climate policy analyst Clive Spash declared that “the aspirational targets bear no relationship to the reality of what governments and their business partners are doing”. In his view, they could not be met without planned, coordinated reductions in the extraction of fossil fuels and unless major emitters were held culpable. Hansen and Spash’s viewpoint was strengthened by fossil capitalism’s contemporaneous commitment to extreme carbon extractives. High-emitting shale oil and bitumen oil projects signified the futility of Paris Agreement aspirations.

The apparent inclusivity of global ecological concern and voluntarist carbon market initiatives obscured the totality of fossil-based global capitalism. Here, Tamara Gilbertson’s critique of such rhetoric and the introduction of NDCs is historically pertinent:

NDCs consist of a series of answers to questions on emissions reduction targets for each participating party of the UNFCCC regardless of GDP, development status or historical responsibility. Thus, the discourse shifted from problematising overconsumption and historical fossil fuel use in industrialised countries, to a narrative whereby climate change becomes an equally shared responsibility of all nations. This essentially whitewashes and erases its history and politics.

From the Kyoto Protocol to the Paris Agreement then, attempted international consensus building over climate goals and carbon emission schemes dehistoricized and depoliticised a global-temporal emergency.

The Anthropocene, Global Capitalism and Global Futures: Times Out of Joint – Professor Wayne Hope

…look.

I believe, and have been arguing for some time, that climate change is the existential threat to late stage capitalism and that the reality and scale of what we face demands urgent and radical solutions.

There are many in agriculture who see first hand the impact of climate change and its increasing intensity.

Those voices are not as powerful as the Dairy Industry and the Pollution Industry and Big Oil.

What those industries want is tepid nothings that look like something is being done while that illusion only makes things worse.

The data doesn’t lie, fossil fuels extraction industries have doomed us to a feedback loop that will make life very difficult in failed state after failed state world.

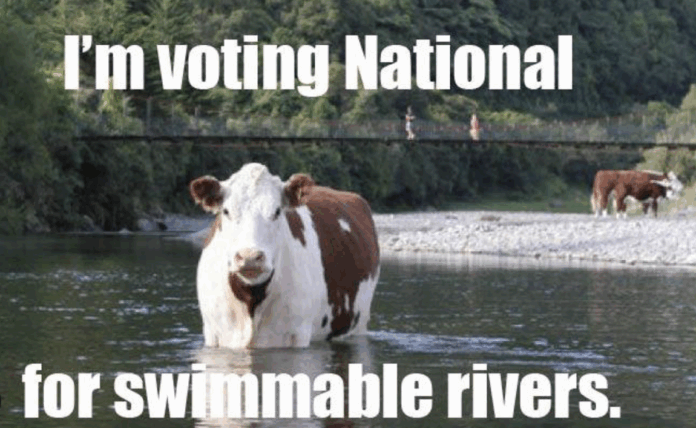

There is a gravity to the problems we face that National as a politic al party beholden to Dairy are in total denial over.

The Greens, with their very excellent Green Jobs proposal, including the Ministry of Green Works that TDB has been arguing for, at least acknowledges the reality of where climate change is taking us…

Greens announce policy they say will create 40,000 ‘green’ jobs

The Greens have announced a ‘Green Jobs Guarantee’ policy it says could create more than 40,000 jobs.

The party released its policy in Tokoroa on Wednesday morning to mark ‘May Day’ that celebrates the international labour movement.

It wants to set up a Green Jobs Guarantee scheme to create 40,797 jobs with stable working conditions and good incomes.

The party also wants to establish a Ministry for Green Works – modelled off the disestablished Ministry for Works – to create around 25,000 jobs in the construction sector and a further 16,857 jobs from economic activity the Ministry generates.

It would expand the Jobs for Nature scheme to create an additional 15,797 jobs over four years.

The party’s plan would create these ‘green jobs’ by setting up a Future Workforce Agency/Mahi Anamata to plan for future workforce needs and link different workstreams that are currently under-resourced.

It wants to fund a renewed Jobs for Nature programme by partnering with local government, community organisations, iwi and hapū to support conservation work.

Part of its plan for the revamped programme would include short-term projects to provide jobs in areas facing high unemployment and longer-term projects to create training pathways.

Its Ministry of Green Works would be an expanded Rau Paenga, which is part of the Crown Infrastructure Delivery organisation.

…National are in complete denial of the truth, the facts and any relevance whatsoever.

Coughlan’s last comments are worth repeating…

The rise of Australia’s climate-friendly Teals at the expense of National’s sister party, the Liberals, should be a warning to any party that doesn’t take climate change seriously. National has avoided a Teal problem thus far. It may not avoid it forever.

National won Auckland in 2023 in large part because Labour’s Covid policy turned the Super City into the world’s largest open-air prison. That memory will fade. The party can’t rely on the memory of Covid to win the city in future elections.

The Auckland-centric electoral calculus that saw National slowly abandon farmers might have been cruel, but it wasn’t wrong. Say what you want about the Key and English government, it never polled as low as this one.

…Auckland, we are cosmopolitan and egalitarian!

Why the fuck are we allowing these redneck National MPs deny the scientific reality we all know to be true.

These muppets are flat earthers at a geology conference!

National out of Auckland, now!

The planet is burning, National are fiddling!

Increasingly having independent opinion in a mainstream media environment which mostly echo one another has become more important than ever, so if you value having an independent voice – please donate here.

Just thinking. The UK industrial revolution proceeded speedily in innovations and efficiency and effectiveness, but human workers got bent into shape, literally down mines. And the profits went into expansion and good living at the top. Catherine Cookson’s novels on that period and around the time of the Jarrow March of unemployed from North England to London was incorporated into one of her books. A miner challenged her to experience it when she wrote about them in other stories, and she did (didn’t like it much)!

We are going through a time of financial and business revolution, with the first sufferers being our cows, the second being our land and water. Our conditions are being perverted by the agricultural business methods, I am thinking of dairy farming here. .In North England the workers might live in very small cottages with stone flags laid over cesspits which might ooze up around the flags. We have similar bad conditions in housing for the low income class, whether working or not.

We are now echoing the same complaints. People, citizens, in our great democracy have been trumped by the very political party started and supported to prevent these conditions. Is there a Party now capable of the strength collectivity determination and vision to go into bat for the ordinary people. And how do we get through our minds that we are prepared to abandon others’ needs and interests in society when we have won a better life for ourselves? Because that is what Labour did – they abandoned the pretence that they cared about ordinary people and returned to the old industrial revolution practice of disdaining the common folk and vilifying them as stupid – and so it goes.

Comments are closed.