The Choice

“INSULATION from the ravages of extreme opinion has been achieved. The settlements have become mainstream.” The words are those of former Labour Prime Minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer. The “settlements” he refers to are the Treaty settlements negotiated between the Crown and Iwi.

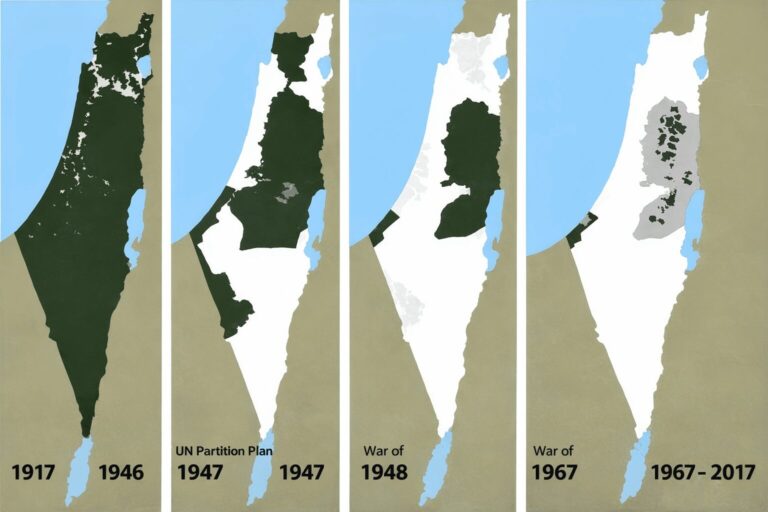

It is to Iwi, New Zealand’s officially recognised tribal entities, that the responsibility for reinvigorating Māori society has been entrusted. Palmer’s confidence that the process has been walled-off from the “ravages” of democratic interference is important. The critical political choice made by leading Pakeha politicians, jurists and bureaucrats in the 1980s and 90s was to halt the momentum of left-wing Māori nationalism by inserting a layer of elite Māori business-people between the Crown and the economically and culturally impoverished Māori working-class.

Only by fostering the rapid growth of a Māori middle-class could the Pakeha state avoid being compelled to negotiate with social, cultural and political forces with precious little to lose. Forces, moreover, whose lack of a meaningful stake in the capitalist system might encourage its leaders to contemplate sponsoring an entirely different set of economic arrangements.

Fostering a Māori middle-class would not only create social, economic, cultural and political forces with a great deal to lose, but, by frustratingkotahitanga – unity – it would protect the Pakeha state from a popular movement it could not defeat – except by the application of overwhelming military force.

Forty years ago, the vital moral truth that Geoffrey Palmer and, following him, Jim Bolger and Doug Graham, grasped was that a New Zealand state strong enough to, once again, frustrate Māori aspirations by force, would not be worth living in.

That historical choice: to forswear force; made by the more enlightened leaders of Pakeha society back in the 1980s and 90s, was crucial. The settlement process – led and controlled by the Crown – would empower and enrich only a fraction of Maoridom. But, this small, highly privileged group would, in their turn, guarantee the integrity of the core institutions of the New Zealand state.

The Iwi institutions constructed out of the capital transfers at the heart of the Treaty settlement process were modelled on the corporate structures of the Pakeha economy. The name given to this phenomenon by Professor Elizabeth Rata is “neo-tribal capitalism”. Like the Pakeha system which inspired it, iwi capitalism elevates a very small minority to great wealth and power, while consigning the majority of Māori to a life of exploitation, deprivation and desperation.

Like capitalism everywhere, it isn’t fair – but it works.

Ironically, the man who came closest to destroying this mutually beneficial system, in which the elites of both ethnic communities gave away a little to get a lot, was one of New Zealand capitalism’s staunchest defenders, Don Brash. Perhaps he intuited that, having indicated their unwillingness to contemplate the force majeure deployed at Bastion Point, the Pakeha elites would inevitably find themselves prevailed upon to transfer more and more power and resources to the iwi-based corporations and the Māori middle-class which serviced them. Perhaps he simply refused to contemplate the evolution of a “bi-cultural” state. Whatever the explanation, Brash’s controversial Iwi/Kiwi election campaign of 2005 brought him within a whisker of discovering exactly how much force it would take to trash the principles of the Treaty and restore the colonial state to its former glory.

Brash’s successor, John Key, moved decisively to restore the relationship between the Pakeha and Māori elites. His reaching out to the Māori Party, and the latter’s positive response, confirmed beyond dispute the truth of Geoffrey Palmer’s assertion that the settlement process had moved beyond the sanction of “extreme opinion” and become part of the mainstream.

Over the course of Key’s nine-year (nearly) reign, the rapidly expanding Māori middle-class grew progressively more nationalistic. That they would promote their language and culture with ever-increasing fervour was entirely predictable. Historically, it has been the practice of all colonised peoples to not only claim full equality with their former masters’, but also to elevate the achievements of their own culture well above that of their brutal conquerors. The strong symbiotic relationship in which erstwhile oppressors and oppressed typically become enmeshed is simply edited out of the ethno-nationalist discourse.

The New Zealand state thus finds itself in a position roughly analogous to that of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the turn of the nineteenth century. The dominant group is no longer confident of exerting its formal (but waning) imperial authority without causing the entire ramshackle edifice to disintegrate. So uncompromising have the nationalist claims of its subject peoples become that meeting them would instantly dissolve the constitutional glue holding the state together. To resist their claims means war. Ultimately, there is no winning move – but surrender.

Certainly, it is difficult to read in John Key’s decision to sign the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and Jacinda Ardern’s decision to allow Nanaia Mahuta to commission a report on its implementation, as anything other than a capitulation to the political logic of Māori nationalism.

He Puapua is an imaginative and honest presentation of the steps necessary to establish a te Tiriti-based constitution based on the principle of co-governance. The fact that its recommendations, which included the elimination of majority rule, failed to elicit any significant protest from Ardern and her cabinet colleagues, indicates just how completely Labour has been persuaded that the future of Aotearoa will be driven by Māori.

The Māori nationalists ideological victory will not, however, be costless. Just as the leaders of Pakeha New Zealand were required to make a choice about the use of force, so, too, will the new rulers of Aotearoa.

It is difficult to see how a system of government permitting 15 percent of the population to determine the fate of the remaining 85 percent can end anything other than badly. Pretty early on in the piece, the Māori nationalists, like the Pakeha liberals of the 1980s and 90s, will also be forced to choose:

Do we preserve our ideological victory and defend our hard won political supremacy by force – or not?

Look what is right in there interfering in our country’s deliberations about the way our country runs.

Delivering better outcomes together | Deloitte New Zealand

https://www2.deloitte.com › nz › public-sector › articles

The cultural and ethnic face of Aotearoa New Zealand is changing. … This report post-dates the amendments to our Overseas Investment rules, ..

We gave up our sovereignty just as we protested about on the street against signing up for open slather trade treaty with hidden whips to keep us in order. And special suction pipes to draw off any profit and good that we have achieved..

The government undertook meetings called Cultural Conversations in 2007. A group of hard-working people of note travelled around NZ and the public were invited to turn up and discuss matters. I was surprised at the vociferousness in a negative way, of many old white men. They behaved just like the stereotype.

There isn’t a great lot about this to be called up on google.

I found this:

https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/connecting-diverse-communities/cdc-public-engagement-2007.pdf

I may be naive, but it seems inconceivable to me that the 85% non Maori citizens of New Zealand would willingly agree to give up the country’s long established democratic institutions, which have provided the governance framework of our society as we know it, so that 15% of the population (Maori) could co govern or, worse, govern autocratically based on the Fijian model.

Even super sales woman Jacinda doesn’t have the communication skills to persuade the 85% to buy that deal.

Trying to impose a framework that gives over power to the 15% is bound to lead to serious civil disorder, or worse. And by sheer weight of numbers alone, I can’t see a good outcome for the 15%.

In the end, if this is the future of NZ, it will boil down to violent power struggle.

Discussion about the Treaty settlements ignores the fact that something has been done, Maori have looked at their history and recounted it to the general population. Government has been forced to do it to appear to have integrity and keep the heat down from boiling. Don’t denigrate everything. Humans never do things perfectly according to all observers. There are obvious faults but don’t deride the positives.

The fact that the dreams of democracy turn out to be a sham in reality doesn’t mean that it is right to throw it out. Trouble is that it needs constant informed attention, sort of like managing the Covid situation. We all need to train to get a licence to drive it. Maori have had leaders who have continued to press for remediation and better ways. On the other hand, the unions should have shown determination and practicality to ensure a better future not dominated by sharp capitalistic imperatives, but I reckon they got captured by capitalism’s materialism and consumerism. ‘People’ declined into the term ‘human resources’.

FANTASTIC Chris – you’ve ignited perhaps the most important discussion yet aired on TDB. That the whole Treaty settlement process can now be seen as so Machiavellian, has been an eye-opener, but one which, once considered, makes absolute evil sense. Yet again Capitalism, under the guise of implementing just settlements, secures its position by setting the proletariat at each other’s throats. No wonder Tory Chris Finlayson was so enamored of it.

The mainstream media doesn’t want to go there but a lot of iwi aren’t happy with the Three Waters set-up either. Smaller iwi in the four vast regional entities worry about being crushed by larger iwi in the decision-making process.

As Chris says, these moves are for the benefit of the Maori elites.

‘It is difficult to see how a system of government permitting 15 percent of the population to determine the fate of the remaining 85 percent can end anything other than badly.’

Actually, in the fake democracy that is NZ (and all other western nations) it is the unelected 0.1% -the transnational bankers and corporations and multi-billionaires- who determine the fate of the other 99.9%. And it is already ending very badly, with much worse to come.

Everything else [not focused on removal of the control of society by the 0.1%] is just distraction.

Yes indeed AFKTT.

When 0.1% own everything how can there be democracy?

D J S

One of the problems with the settlements always seemed to me to be the farcical monetary valuation of land and assets returned; as if monetary values at the time of illegal or just wrong dispossession were compensation that could restore tribal descendant’s present day losses.

The only way this could have achieved what it purported to achieve was to transfer the assets back to the original dispossessed owners lock stock and barrel , and compensate with money the latter day owners at current value. It would have been painful for me among many others , and perhaps placed much of NZ’s vital infrastructure in the hands of incompetent or inexperienced managers, but settlements that were an irritating token that are never going to be settled to anyone’s satisfaction were and are an endless source of strife.

D J S

David Stone: “The only way this could have achieved what it purported to achieve was to transfer the assets back to the original dispossessed owners lock stock and barrel , and compensate with money the latter day owners at current value.”

Thus notion is prima facie attractive: sounds like justice, even.

But there are at least two problems with it.

In the first instance, it’s unjust. That’s because nobody now alive stole those assets from the indigenes. Expropriation of land and so on from contemporary owners is forcing them to pay for the sins of – for the most part – somebody else’s ancestors. Even if their ancestors were responsible for land theft, they’re still being asked to pay for something done long before they were born.

Secondly, there’s no mention of land stolen from Maori by other Maori. Much of that occurred long before first European contact, but it’s also happened since. Maori confiscation of the Chathams is a signal example, but by no means the only one. There was land stolen in the course of the musket wars. And then there’s the dispute over ownership of the Auckland isthmus: Ngati Whatua’s claim to own much or most of it is disputed by Te Taou: a relative discovered this history as part of research for an academic project. And that dispute arises as a consequence of the workings of the Maori land court, when Judge Fenton headed it.

So. Any attempts to remedy past injustices by handing back land and assets will create further injustices. As a society, we’ll be no better off.

“So. Any attempts to remedy past injustices by handing back land and assets will create further injustices. As a society, we’ll be no better off.”

Reply

I completely agree with this D’Esterre, It’s another matter.My point was that the claim to be redressing past injustice was always insincere .It can’t be done without massive present day injustice.

It is hard to put away an empathy for many Maori who know the details of their dispossession though. At the time of the Roger Douglas takeover of the Labour party I joined to try to find if there was any grass roots opposition to his philosophies . Esp seeing that Jim Anderton seemed to be the only political voice clearly opposing it. (Before he formed the NLP.

I went around meetings and conferences with the local candidate who turned out to have a grandmother who was the technical owner of lots of land around and north of Kennedy Bay. descendant of the original surveyor of the area had been quietly paying the rates on that land for years knowing that the grandmother had no way of e=doing so. The now candidate had gotten a job at the local council and called the man on what he was doing, saying as he fronted up ” That’s my grandmother’s land” He quietly withdrew and the land was saved, but how much land has been transferred to European ownership by this method in the times long since the original wars and acquisitions.Using the law that if you pay rates on a property for 7 years you can claim ownership.

The Maori land dpt. decided that Maori owned land under their jurisdiction should be divided equally between the descendants of the originally identified owners. This set up a situation where the share of any individual was so small that no part owner could do anything with it. farming it would be for everyone and no individual could survive on the share of returns that running it would return, so no one could feel responsible to contribute either to paying rates or generating any revenue from the land to pay them with. It is land lost in this era that i think deserves most attention.

D J S

David Stone: “….the claim to be redressing past injustice was always insincere .It can’t be done without massive present day injustice.”

True enough. But nonetheless, that’s how the 1990s settlements were sold to the population. It was accepted that the amount was a fraction only of what had been lost, but it was a good-faith attempt to put things right. It wouldn’t be possible to make full-value restitution, because that would involve the expropriation of private property, a path down which the government wisely would not go. (Though with regard to Ihumatao, the current PM has incautiously rushed in where angels fear to tread, it seems.)

We were also given to understand that these were the first settlements. They weren’t. The first was in the 1920s, with another round in the 1940s. Of course nobody my age was born then, so we had no recollection of them. Some older citizens pointed out this fact by means of letters to the editor and the like, but I don’t think the media followed it up. In any event, the zeitgeist of the time was to be in favour of the settlements.

“….empathy for many Maori who know the details of their dispossession…”

Also true. But it would be disingenuous to claim that all such events were carried out by pakeha. They weren’t, of course. Humans are humans: Maori were and are as likely to behave duplicitously as anybody else. But there was some awful stuff in respect of land theft by pakeha that happened in the South Taranaki/Northern Wanganui area. If you haven’t read it, “The Fox Boy” gives an account.

It’s instructive to note that many Maori fought with the Crown during the land wars; that’s doubtless a reflection of the fact that many tribes had lost land to other tribes in the pre-European era. Curiously, Ngapuhi were among the government’s strongest supporters, notwithstanding the chicanery and sharp practice there had been by some missionaries in respect of land acquisition in that area.

In the Wanganui area, the upper river tribes also fought with the Crown. We grew up there, heard that story from locals. Those living on the upper river were escaped slaves and their descendants: as Elizabeth Rata points out, the Treaty was the best thing that had ever happened for them, because it abolished slavery. No surprises that they’d support the Crown.

“It is land lost in this era that i think deserves most attention.”

Yes, there are some sad stories indeed. That of Te Taou in the Auckland isthmus is a good example: that happened under the aegis of the Maori land court during Fenton’s time. My relative thinks it likely that there’ll be another Tribunal claim over that issue.

And the department of Maori Affairs was also responsible for injustices, despite good intentions. The issue of multiple owners of land was always going to be complicated, though, and doubtless remains so.

I remain a supporter of attempts to resolve land issues, where it can be done without causing further injustice. However, I’m now sceptical about the value of the so-called Treaty settlements. It’s very clear that most of the very poorest Maori haven’t benefited at all. That was a large amount of taxpayer money applied to those settlements: we the taxpayers at the time are within our rights to ask for accountability. Where has all that money gone?

With regard to the land issue, those of us who are descendants of the Irish and the Scots, who lost land to the English, are well aware of the resulting grief, along with the economic effects of dispossession. That in part is of course why many of us are here.

The tougher question is how to resolve the issue, such that this country isn’t left with the sort of disaster which pertains in Zimbabwe and South Africa. I’m not sure how that could be done.

A couple of points:

There are no “principles” in the Treaty. They are a modern fiction.

Europeans arriving in NZ weren’t “brutal conquerors”. They were gum diggers, whalers, sealers, missionaries and later farmers. The brutal people were those already living here, where utu, cannibalism and slavery predominated.

No mistaking your colours Andrew. But I think you’re wrong on a few counts. It may well be the case that the colonialists in early New Zealand weren’t brutal in the traditional sense (although that’s up for interpretation) but like colonialists everywhere they brought with them, for the most part, an arrogance that could have easily be mistaken for insensitivity. At worst a kind of inhumanity that gave no acknowledgement to language nor culture. The modern fiction is that we (us pakehas who went to school here) weren’t told that. It wasn’t part of the narrative. I grew up in rural Northland so there was always a backstory – as I suspect in other rural areas – but I was too young to know (and too pakeha to care). It took a while but James Belich, Michael King and others changed that, as did the so-called Māori renaissance, push-back against the Crown for acknowledgement and recognition. The other side of history is laid bare for all that wish to look. We now have to live with that history, both Maori and pakeha, and if Māori nationalism at the hands of a neo-tribal elite is the price then so be it. To be frank, it saddens me that folk like you still walk this land.

Everyone knows that Andrew is not wrong; he just isn’t at all PC.

D J S

By everyone, you mean D J S?

Bozo, you said I was was wrong on several counts but then only said you thought settlers were arrogant. Maybe they were indeed arrogant but its hard to know 200 years later. If arrogance was their worse sin, let’s forgive them eh?

Meanwhile the poor Maori existed in a living hell of brutality that only ended with the signing of the Treaty, the arrival of more settlers to moderate their behaviour and the widespread adoption of Christianity.

I’ve just finished reading ‘The Musket Wars’ by RD Crosby. I thoroughly recommend it.

Andrew, I was speaking metaphorically, referring to the kind of cultural arrogance associated with the times. It’s still alive and well.

Literally speaking, many of these settlers may well have been arrogant. Of course. It’s a common enough human trait irrespective of historical context. But not universal and I suspect there would have been some respectful, if not fully understanding of the ways of the indigenous people they encountered here, indeed in other places were the old world clashed with the new.

There is an argument that indigenous peoples had no history, were lost in timelessness before the arrival the old world into their universe. The counter argument is that they themselves were complicit in creating the tapestry of what we now know as history. The musket wars an example. The slave trade another as east African elites greatly benefited from the partnership, eager to extent their power and territory. It’s an argument that says not all indigenous peoples were ‘victims’ and, for some, had their own hand to play. But this view is rather unkind to, say, Australian aborigines. By anyone’s standard they got a pretty raw deal with the arrival of the the white fella.

Judging the historical actions of those who inhabited a different world is fraught with difficulty. But we could go down a rabbit hole on this one and end up justifying all sort of things that happened because people didn’t know better, or were simply swept along by the currents of the day. It’s passe to say that history matters. Equally so, without it – and I mean a history written by both the victorious and the vanquished , as well as the view even the vanquished had a hand to play – we know not the present.

Bozo: Andrew is correct.

A family member has relatively recently been researching the documented oral history of pre-European Maori habitation and conflict in the Auckland area. Prior to first European contact, NZ wasn’t a bucolic paradise: it was Hobbesian. Tribes were ruled by hereditary elites; slavery was the norm. Inter-tribal conflict was frequent and violent, cannibalism routinely practised. Much of that conflict was very likely to have been driven by the pressure of diminishing food resources. The Royal Society has referred to this here:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.160258

Many years ago at uni, I read a paper on this topic. It postulated that, if Europeans hadn’t turned up when they did, and brought food resources with them, there’d have been a large scale population crash caused by starvation. I cannot now locate that paper, unfortunately.

When the first European explorers arrived in the Auckland isthmus, the population was very low. That was because of the depredations of Ngapuhi in particular (though not exclusively): people had mostly fled.

Although the musket wars were over by the time of the Treaty’s signing, it was the spectre of a recurrence which was among the reasons why chiefs were willing to sign. And you’ll doubtless be aware that it was Hongi Hika’s acquisition of muskets which started those wars.

Note that it’s possible to have a discussion about Maori rights and so on, while at the same time accepting the unvarnished truth about pre-European Maori society.

“…no acknowledgement to language nor culture.”

It’s important to remember that it was Maori elders themselves who petitioned parliament to prevent the use of Maori language in schools. They reasoned – logically enough – that children would still learn the language in the home, and would therefore be native speakers. In the 1970s, when I was a young adult, I was taught the Maori language by a native speaker, so such people were still around by then. And the culture remains alive and well.

“…Māori nationalism at the hands of a neo-tribal elite is the price…”

I don’t think so. Democracy it surely would not be. I doubt that you’d be any more willing than the rest of us to give up those democratic rights you take for granted.

That’s right Andrew, the Europeans were all such wonderful people. Just like the settlers of the USA. sarc.

So the colonial soldiers never raped and pillaged Andrew sounds like you need to learn New Zealand history and take of your white blinkers why you are at it.

Yes Andrew, different times.

It’s difficult for us to comprehend today, especially given the wall of misinformation (now officially incorporated into our children’s school lessons) just how brutal things were.

By some estimates a third of Maori were killed in the early 19th century tribal wars. More deaths than all NZers killed in both world wars and entire settlements, men women and children, destroyed. Captives and slaves were treated no better that livestock. My ancestor Hongi had them corralled near where I am today, to be unceremoniously murdered and butchered for food.

Hongi never converted but it was only after Christian morality was introduced that this sort of thing was regarded with abhorrence.

There is no doubt that the European settlers and authorities treated Maori better than they treated each other.

Yes indeed.

They lived a Hobbesian existence: “Nasty, brutish and short”

For the romanticists among us, ask yourself how the town of Kaitangata got its name 😉

Andrew: “There are no “principles” in the Treaty. They are a modern fiction.”

Exactly. The so-called “principles” were a post facto attempt to freight meanings on to it that went far beyond what the text can bear, or the signatories could have imagined or intended.

Geoff Palmer was largely responsible: I am among the many people who, at the time, heard him trying – and failing – to explain them. Winston Peters was one who called him out on it.

“It is difficult to see how a system of government permitting 15 percent of the population to determine the fate of the remaining 85 percent can end anything other than badly”.

And so will begin the rise of NZ European / white nationalism in NZ . .

Eloquent rhetoric Chris but could you please explain or paraphrase some more of this dreaded ‘he puapua’ document for the proles to chew over? thanks!

gin hag: “….could you please explain or paraphrase some more of this dreaded ‘he puapua’ document for the proles to chew over?”

Here it is, in its entirety. Happy reading!

https://www.nzcpr.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/He-Puapua.pdf