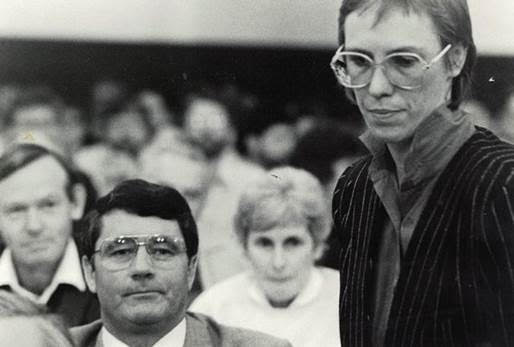

Ruth Dyson moves towards the stage of the Dunedin Town Hall after defeating Jim Anderton for the Labour Party Presidency by 572 to 473 votes. Saturday, 3 September 1988.

THE LAST TIME the NZ Labour Party held its conference in Dunedin the stakes could not have been higher. Those for whom the Labour Party represented democratic-socialism were pitted against those for whom the Labour Party represented electoral pragmatism and the fulsome praise of New Zealand’s leading capitalists. In other words, it was a straight-out fight between the Left and the Right.

Tragically, the Right won.

Had Jim Anderton been elected President of the party (as he would have been, had the Engineers’ Union boss, Rex Jones, cast his 55 votes with the other affiliated unions supporting him) there would have been no NewLabour Party, and New Zealand Labour would become a Corbyn-style left-wing party long before its British namesake.

Anderton’s plan was simple: to have his allies on the Executive and Council of the party oversee the de-selection of the leading exponents of “Rogernomics” (Roger Douglas, Richard Prebble, Michael Bassett, Mike Moore) and ensure that their replacements were reliable opponents of the far-right policies these “Rogernomes” had introduced.

Anderton was well aware that de-selection would trigger a full-scale crisis within the party. Richard Prebble had already shown how far the right of the party was prepared to go by legally injuncting the entire NZ Council of the Party from installing a hostile (but duly elected) electorate committee in his Auckland Central seat. At that time (May 1988) it was made clear to the party organisation that Roger Douglas’s supporters in the Labour caucus were willing to split the party rather than see Labour return to its traditional left-wing beliefs.

Anderton’s strategy was to call their bluff – precipitating their defection from the Labour Party. They would, presumably, be followed by their supporters in the Labour Party electorate committees and branches. Such a course of action would, in all likelihood, have caused the government to fall, requiring an early general election. Labour, purged of its free-market cuckoos, would have been free to run as its old self. The Rogernomes’ new party, hamstrung by the First-Past-The-Post electoral system, would have been defeated, and the Labour Left would have come into its inheritance.

The Labour “centrists”, led by Helen Clark, were horrified by the prospect of Labour moving so decisively to the Left. They may have hated Roger Douglas and his allies, but they feared Jim Anderton and his comrades much more. Rather than see the party split to the right, they prevailed upon the Rogernomes and their hard-line supporters in the infamous “Backbone Club” to acquiesce in the election of Ruth Dyson. The centrists hoped that Dyson, a senior party office holder with an honourable left-wing past, would encourage just enough of the rank-and-file to remain loyal to David Lange and his government – thereby ruining Anderton’s plans. Which is exactly what happened.

Did Clark and her centrist allies understand that by ensuring Anderton’s defeat they would be making a split to the left well-nigh inevitable? Almost certainly. But why would that worry them? Their strategic position would be secured by Anderton’s and the Labour Left’s departure. Moreover, the party’s inevitable defeat in 1990 would make it possible for them to appropriate Anderton’s de-selection strategy and make it their own in the run-up to 1993. The hapless Mike Moore could be duped into carrying the can for Labour right up until the moment Clark had the numbers to depose him – which she duly did just weeks after the 1993 General Election.

The Labour Party that last weekend returned to Dunedin, thirty years after the dramatic events of September 1988, is the inheritor of all that ideological and personal treachery. What’s more, it is a party that has never confronted and acknowledged its own wretched complicity in the events that inflicted so much harm upon it back in the 1980s. It came very close in 2012 – at the Annual Conference held at Ellerslie – but, once again, a frightened leadership saw to it that the past remained unexamined. A pity, because as any theologian or psychotherapist will attest: sins unrepented have a nasty habit of repeating themselves.

In this regard, it was certainly fascinating to read Richard Harman’s account of the 2018 Annual Conference in Dunedin. The most notable feature of which he described as the “airbrushing” of Helen Clark out of Labour’s recent history:

“The weekend Labour conference saw the party rule a line under the last 30 or 40 years of its turbulent past and launch what in effect is a new Labour Party.”

Harman argues that “the new ‘progressive’ party is very much the product of the leader, Jacinda Ardern, with a new emphasis on pragmatism and the realities of MMP coalition government.”

The political legacies of Lange, Palmer, Moore and Clark went unacknowledged, says Harman: “[T]hat would have brought back too many horrific memories of the last time the party had a conference in Dunedin in 1988 and nearly ripped itself in two over Rogernomics.”

What Harman doesn’t say is that the only reason such political legerdemain is even possible is because Jacinda Ardern is such an extraordinary electoral asset. Single-handed, she has resurrected Labour’s morale; refilled her coffers, boosted her membership, and filled her activist base with confidence and delight. Her “relentlessly positive” personality is like a powerful spotlight, illuminating brilliantly that little part of Labour’s stage upon which she sits and smiles. Meanwhile, in the darkness her brilliance does so much to render impenetrable, the party leadership does all within its power to render a genuine shift to the left impossible.

It is fitting, in a way, that the decision to free the caucus from its crucial constitutional obligation to uphold the party’s manifesto – its policy platform – was taken in Dunedin. Justified as a practical and necessary concession to the exigencies of MMP, it nevertheless severs the last of the ties that bind the parliamentary wing to the party organisation. The caucus is now officially “Corbyn proof”. Thirty years after stabbing her in the back, the centrists have finally summoned-up the courage to drive the dagger of pragmatism deep into Labour’s democratic-socialist heart.

Trotter’s saying that unfortunately that’s going to be continuing for a while yet. And I think he’s right. It’s not pragmatic to look after the poor. Our culture has become one in which compassion and caring for those less fortunate is punished. This needs to change so that looking after ther poor is regarded as pragmatic.

Or you’re into politics at which point your one job and function is to embarrass as many enemies as possible. In this case making it impossible to take money and shelter away from poor people because the economies doing so well no one would have a right to complain.

Oh. So the resolution to bring in free dental care after 2020 has no teeth.

Have they signed their win death warrant?

There seem to me to be two long term possiblities – A new party rises to the left and Labour ends up in coalition with National or normal people mount a take over of the Labour Party itself – because it can never be truly Corbyn proof if the members don’t want it to be.

It will happen, it’s just a question of when

Making the party Corbyn proof does not at the same time make it proof against challenges from the populist right. In fact it makes it more vulnerable to such challenges. Once good will starts wearing thin, all the populist right has to do is refrain from looking snobbishness or condescending and shout variations on “These people don’t give a stuff about you,” a claim to which the suppression of the left lends substance. Moreover, should push come to shove, we do not know whether Jacinda would choose her brand or the NZ Labour Party as the thing to be saved.

Hi Chris, as I’ve commented on your Facebook page, this is incorrect. The Constitution still requires any departure from the Party’s Policy Platform to be put to the Policy Council for approval (and requiring a 2/3 majority of Policy Council). The piece of the constitution that you refer to specifically relates to the coalition and confidence and supply agreements. Under MMP, parties need to be able to negotiate with other parties.

Comments are closed.