Primary and secondary school teachers engage with students who are constantly on devices — consuming, sharing and jointly creating texts, photos, videos and memes.

Across social media, hate speech, conspiracy threads and health disinformation swamp evidence-based material. Fabrications and fragmentations of reality cannot be challenged in real time.

Despite this massive influence on young minds, the government intends to remove one of the few teaching opportunities that might equip students to navigate their online world.

Along with several other subjects, secondary school media studies will be dropped from the level 1 curriculum of the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) from 2023.

This is a backward step. Making sense of today’s hyper-mediated world depends on the availability of robust media studies courses in primary and secondary schools.

Young inhabitants of this world serve only to reproduce an “attention economy” shaped by the business models of social media and mass media corporations. They need the critical skills to understand this aspect of their lives.

Furthermore, recent medical research suggests excessive smartphone and social media use among adolescents is associated with mental distress. The social implications of this are disturbing.

Media studies may disappear

At present, level 1 media studies students learn about regulation of media content, analyse media coverage of current events, examine and compare media genres and production technology.

Over the next two years, they evaluate media texts and representations, develop a range of journalism skills across different media and explore the workings of particular media industries.

The entire three-year curriculum advances critical thinking and foundational media literacy. Students appreciate how media texts are constructed and disseminated and how different experiences and viewpoints shape the readings of such text.

After secondary school, media studies students are equipped for tertiary-level courses in communication studies, film production, journalism, radio, visual media, art and design, general humanities and the social sciences.

Without level 1 courses, the risk is that some schools may abandon the subject altogether. Fewer media studies courses will reduce the number of qualified teachers available. Media studies pathways will, inevitably, disappear.

This bleak scenario was outlined to me by a senior media studies teacher from the National Association of Media Educators (NAME). For her, the government’s decision is short-sighted and contradictory:

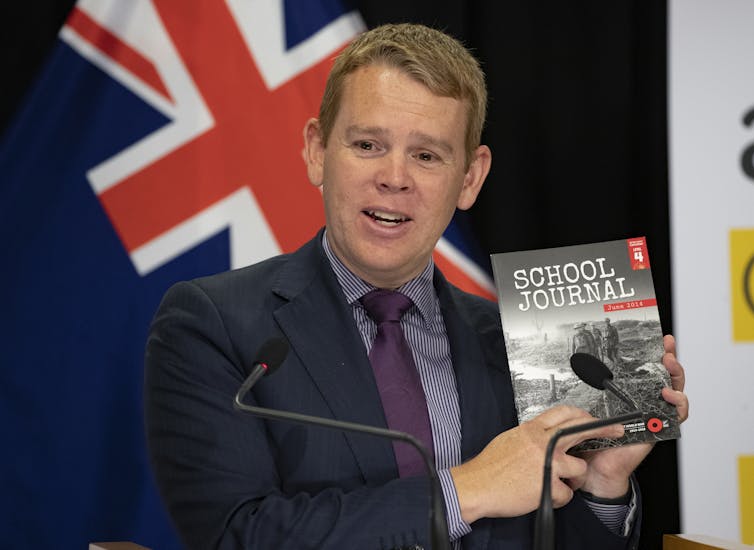

I find it hard to believe that Chris Hipkins, as minister of health and COVID response minister, can warn how everyone must avoid misinformation with regard to dealing with COVID, but then as education minister agree to remove the subject that most equips students with the skills to avoid misinformation — there is such a dissonance happening here.

I would add that Prime Minister Jacinda Adern’s accurate distillations of COVID-19 science reflect her own media education — a communications degree from Waikato University. This strengthens the case for robust media studies courses at secondary level.

No political debate

The Education Ministry’s rationale is certainly hard to fathom. Its December press release was headlined: “NCEA Level 1 changes give students a broader foundation” — the implication being media studies are a narrowly defined pathway.

Such an assumption ignores the disparate origins of media studies research and the range of knowledge available to student learners.

The growing pervasiveness of mass media and digital media communication has brought together the insights of journalism, history, literary studies, political studies, economics, sociology, anthropology and psychology. These are the raw materials for secondary school and tertiary media studies programs.

Alas, media educators’ criticism of the government’s proposals has not generated party-political debate. Rather, Hipkins’ unsupportable claims are complemented by National Party leader Judith Collins’ derogatory remarks:

The problem with secondary schools now is there’s too much photography and too much media and other woke subjects.

Clearly the government and opposition are of one mind — student media literacy is not a high priority.

Losing historical memory

Meanwhile, New Zealand primary school pupils use digital technology throughout the curriculum to develop their knowledge, skills and cognitive understanding. No complaints here — immersive digital learning recognises the omnipresence of networked screens, online platforms and computational intelligence.

However, an historical appreciation of communication technologies is also required. Phonetic alphabets, manuscripts, printing presses and telegraph/telephone networks necessarily prefigure the internet and social media.

Without this background knowledge primary school pupils risk becoming ciphers of a hyper-mediated present in which transitory information and imagery annul historical memory.

Without a sense of past and present pupils will struggle to separate verifiable journalism from clickbait, infotainment and orchestrated propaganda.

Yes, there is digital education available for both parents and pupils, including internet safety programs to counteract stalkers, scanners, cyberbullies and porn merchants. While crucial, this kind of media literacy is insufficient.

Greater media literacy is vital.

The fundamental reality is that social media are not a neutral means of communication, content creation or information transfer. From late primary school, digitally aware students should be investigating the origins, motivations and tactics of disinformation networks such as QAnon and COVID or climate change denial.

Classroom activities might reveal how we spread disinformation inadvertently by sharing videos, using hashtags and adding to comment threads. As a recent Scientific American editorialreflected, “Each one of us is a node on the battlefield for reality.”

Correspondingly, students might share their experiences of Google and Facebook advertising and consider why users are encouraged to spend more time on sites. Final-year secondary students will, ideally, have answers to the following questions:

- why did Twitter belatedly terminate Donald Trump’s account?

- how does Facebook profit from extreme violent content?

- how does one obtain reliable information about the COVID-19 pandemic?

Finally, a question for the education minister and his officials on behalf of media educators everywhere: should aspiring citizens be more or less media-literate than they are now?

First published on The Conversation:

Children would be far better served by the ‘education’ system if the digital devices were turned off altogether, and genuine practical skills relating to the growing of (or acquisition) of food and preservation of health were taught: after all, we are headed into a world in which there will be no no consumerism, and no health system -other than what can be provided locally- and no electricity, nor any centralised systems which are dependent on fossil fuels or electricity, and for many people little of no food.

Indeed, such is the level of failure of governments across the globe (and very much the case in NZ) the Earth is likely to rendered completely uninhabitable for humans by the end of this century, if not well before the end of the century.

However, the level of ignorance (a consequence of the dismal performance of the grossly underfunded ‘education’ system’ over many decades) and the level of denial of reality (also a consequence of the ‘education’ system, but additionally a product of the manipulation of society by short-term vested interest groups) are SO HIGH the government and the bulk of the population are completely clueless about what is on the horizon: they still believe -in the face of all the evidence to the contrary- that Industrial Civilisation has a future and will prevail; it doesn’t; it won’t. Indeed, in some part of the world the wheels are already falling off.

‘4 Million Texans Without Power Amid Grid Collapse, As Second Storm Nears

Update (1003 ET): Some Texans have been living in their cars to stay warm as rolling blackouts have left millions without power.

CBS DFW spoke with at least one person who’s been sitting in his car since Sunday to get warm.

Collin County resident Clint Cash has had no power in North Texas for a couple of days. He said his house went dark Sunday, which was when he decided to bundle up and sit in his parked car with the heater on full blast. ‘

https://www.zerohedge.com/weather/4-million-texans-without-power-amid-grid-collapse-second-storm-nears

Not surprisingly, with environment collapsing, with the economy collapsing, with much of the infrastructure collapsing, and with politics in complete disarray, the looters-and-polluters club of America are now primarily concerned with the performance of the manipulated ‘casinos’ they call the markets; the biggest bubbles in history have already been blown, and the plan is to blow them even bigger via further injections of fake money. Just like the Roaring Twenties. And we know how that ended.

I wonder whether the phony nature of the money system (and it’s impending implosion) could be taught in schools. I guess not. Nor the fact that global extraction of oil (upon which the entire economic system is dependent) is on the cusp of severe decline (if not outright collapse).

Maybe children could be taught that the world is finite, and that the notion of infinite-growth-on-a -finite-planet [that politicians and economists believe in] is ridiculous. They probably know that intuitively already, and have to have the notions of limits to growth beaten out of them by the ‘education’ system.

Oh well, not long to go before collapse overtakes the system and brings it down. 2025? 2030?

https://ourfiniteworld.com/2021/02/03/where-energy-modeling-goes-wrong/

We are on a hiding to nothing and it is only going to get worse – my oldest is 15 and is on his phone all the time / pretty much believes anything that he reads online.

Really starting to feel that the internet is making apart society / civilisation as we know it block by block and not for the better.

A pundit named Geoffrey Vickers once wrote that the most remarkable thing about the continuity of an increasingly complicated civilisation since the age of the Vikings was that it had depended, forty times over, on every single new generation somehow gaining all the knowledge of its elders and adding to it. Seriously interrupt this daisy chain for one generation and you are back to the Vikings (who had their own oral history of course). Or as Kenneth Clark famously put it, however solid it may seem, civilisation is really quite fragile: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KNQRqJitqNI. I do wonder whether most of our politicians operate on the same plane of thoughtfulness as people like Vickers and Clark . . . (joke).

Some great points Wayne. I know the school curriculum is crowded but it beggars belief in an age of digital communication and the increasing need for critical engagement – in a word media literacy – that Media Studies would be a target. The danger as you note is that if dropped from Level 1 some schools may not offer it at Level 2 or beyond. Another disadvantage would be the potential failure to generate interest (and criticality) at an earlier age – although it seems the case in primary education (in your own words) that immersive digital learning recognises the omnipresence of networked screens, online platforms and computational intelligence. The curriculum begins well in that it helps develop kid’s knowledge, skills and cognitive understanding of digital technology and its uses.

Without knowing the primary curriculum in detail this however may just be skills-based – although skilful teachers will always try to incorporate a critical component. What the decision to drop Media studies from NCEA Level 1 indicates is poor understanding at the Ministry of media literacy and what criticality really means for literacy and for education. Educators – at all levels – have struggled with this for some time.

Having said that I am not sure what the current Level 1 Media Studies curriculum entails. But your suggestions that from late primary school (and by NCEA Level 1), digitally aware students should be for example, investigating the origins, motivations and tactics of disinformation networks such as QAnon and COVID or climate change denial. Does anyone know WHAT is actually taught in the curriculum? Or does JC (not the bearded one) – I hate to say?

I have a suspicion the AO/NZ curriculum has struggled with incorporating criticality – not necessarily the teachers I might add. Two Aussie academics had a go at putting the situation right a few years back, initially with regard to print literacy then adapted to new screen-based digital literacies. I am uncertain to what extent their framework made it into school-based education in Australia – but in my view Ministry in AO/NZ has struggled with frameworks such as this preferring skill-based learning progressions and the like. But I wholly agree: dropping it entirely from Level 1 lacks foresight.

For those not familiar with the Four/ Five Resource Model:

https://in.pinterest.com/pin/80220437083655538/

https://sites.google.com/site/dlframework/

Error

Or does JC (not the bearded one) – I hate to say – have a point?

“develop a range of journalism skills across different media”

This is for tertiary level. Primary school kids being groomed for a journalism career? Journalism is a declining occupation with shite pay.

“the subject that most equips students with the skills to avoid misinformation”

No it isn’t. Anyway it is not skills but knowledge and experience that detects misinformation.

“After secondary school, media studies students are equipped for tertiary-level courses…”

That is tits backwards. English, Maths, Science, History is a good foundation for media studies.

You could easily have a broad subject Technology and have Media Studies as part of that, along with the rest: programming, hardware, digital content. Then more specialisation in the later years of study as students find their interest withing the subject.

I started Secondary teaching back in the 1970s, before the introduction of Media Studies. Advertising techniques were studied as part of the English course, and there was already a general awareness among teachers that one of the most important things our students would need in life was a fully-developed bullshit detector. I still think teachers in all areas should be striving to instill that.

It now occurs to me that in all the enthusiasm for allegedly standard-based assessment, English teachers inadvertently allowed the study of the language of advertising to be expunged from all Unit and Achievement Standards.

If so, that would be highly convenient for our Commercial Influencers, wouldn’t it?

This is a sad, sad, thing and I think you have hit the nail on the head about the education ministry promoting ‘data’.

Comments are closed.