The Tuesday announcement by Climate Change Minister James Shaw that the Zero Carbon Bill will be passed by the end of the year is a big victory for this Government, following a number of key disappointments around taxing capital gains and glacial welfare reforms. The legislation certainly has its critics from both sides (and rightly so), but we finally have some bipartisan movement on our generation’s nuclear-free moment, as the Prime Minister declared in October 2017 soon after entering office.

The legislation proposed a ‘split-gas approach’, whereby emissions like carbon dioxide – which are less immediately harmful but more persistent – are subject to more initial stringent targets, while short-lived but more damaging gases like methane are given a long phase-out period. This is a concession to the agriculture industry, which is responsible for around half of NZ’s emissions, mostly in the form of methane.

However this announcement got less attention than the latest offer of 2200 square kilometres of land around Taranaki for the controversial process of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas, or ‘fracking’. Green MP Chloe Swarbrick explained to her followers that this under the current law this was an administrative decision, while Energy Minister Megan Woods was quick to note that among the offer’s benefits was that it didn’t include offshore oil and gas. But why frack now?

What is fracking?

Many communities have voiced their opposition to the decision. Local iwi have expressed their concern over potential impacts of fracking in their ancestral land, with Ngāti Ruanui chief executive Debbie Ngarewa-Packer asking “what happens if they ruin our whenua and then go off when they have found nothing and dug holes everywhere?” Similarly Climate Justice Taranaki have raised the red flag on the climate emergency, launching a petition to oppose the decision.

Bizarrely, fracking didn’t get a mention in the Ministry for the Environment Environment Aotearoa 2019 report, which clearly identifies climate change as one of its major themes. And yet in Russia, China, the USA and Australia fracking has become one of the most important areas of discussion on environment and energy.

The fracking boom in the USA – a country whose conventional oil supplies peaked in 1970 (kept on life support when extraction began in Alaska in the 1980s) – pushed US oil production back to those record levels of 10 million barrels a day in November 2017, likely surpassing Saudi Arabia and Russia sometime last year to become the world’s largest producer again.

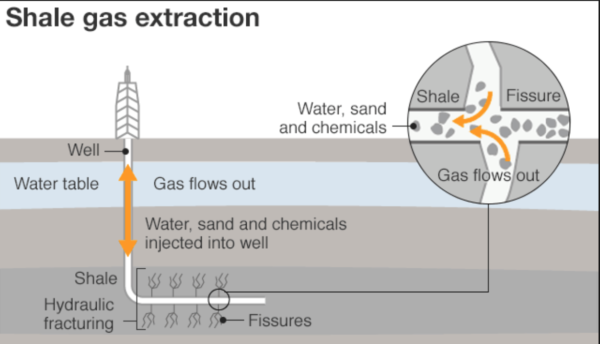

A closer look at fracking is helpful to understanding how we got to here. Fracking is not liquid fuel extraction as we know it – it involves blasting highly pressurized liquid into deep rock formations, forming tiny cracks out of which pockets of oil and gas are able to emerge. As with other non-conventional extraction techniques, the environmental risks are much higher, as are the overall carbon emissions.

In particular, fracking’s methane emissions are much higher than conventional extraction, which brings us back to the Government’s split gas approach: these gases have a longer phase-out period under the proposed law, meaning that it’s possible to still reach the targets set under the proposed legislation. However, with students striking across the planet for an end to fossil fuel extraction, the question must be asked, is ‘because we can’ a good enough answer?

Fracking and the global energy outlook

The fact that we’re even having to consider such unorthodox extraction techniques is evidence that perhaps the global oil outlook is much more fragile than we think. As the International Energy Agency noted in its 2018 World Energy Outlook, with no new investment, global oil production would halve by 2025, resulting in an average loss of nearly 6 million barrels per day. This was on page 159 of a paywalled report, so you probably didn’t just happen across it.

Of course the idea that there would be no new investment in the oil sector is outright absurd. Just a month ago, state-owned Saudi Aramco offered bonds to investors, expecting around US$10-15 billion in new investment, topped US$100 billion in orders.

Adding to this is the suggestion by the IEA challenging the conventional wisdom that oil demand will peak; instead their March 2019 World Oil Report expects demand to grow by an additional 7.1 million barrels per day by 2024. In October last year the world hit one hundred million barrels per day for the first time ever.

The IEA puts hope for reaching those targets squarely in the hands of the US fracking boom, with Executive Director Fatih Birol noting that the “second wave of the US revolution is coming … [which] will see the United States account for 70% of the rise in global oil production and some 75% of the expansion in LNG trade over the next five years.”

However the long-term viability of that boom has been called into serious doubt. As geologist J David Hughes writes in the exhaustive 2018 report Shale Reality Check, “the nature of these reservoirs is that they decline quickly, such that production from individual wells falls 70-90% in the first three years, and field declines without new drilling typically range 20-40% per year.”

Indeed investigative journalist Bethany McLean notes that some of the biggest sceptics of the fracking industry can be found on Wall Street – in 2017 the 60 biggest exploration and production firms in the US industry were not generating enough cash from their operations. One of the key reasons for this was their rapid rate of decline.

The requirement for constant drilling activity means heavy capital expenditure, meaning fracking requires high oil prices to turn a profit. It is no surprise, therefore, that while fracking technology has been around for decades, it was only after geopolitical factors (like the Iraq War) and unprecedented speculation in the oil market that prices reached a level where fracking was considered.

Where is our just transition?

Recently PM Jacinda Ardern moderated her statements about climate change being our generation’s nuclear free moment, noting that the public just wasn’t unified on this issue. A conference taking place in Taranaki over the last couple of days calling for a Just Transition has been a critical part of rallying some of the key actors affected by the transition – most notably workers and their unions – towards engagement on the issue.

However unless we’re looking at the energy picture alongside the issue of climate change then we’re going to consistently struggle to build the necessary consensus. Given it takes between five and ten years to bring new oil production onto the market, it’s possible that the Government has made a prediction in line with the IEA that by 2025 there is going to be some serious shortage.

It’s also possible that this remains a bit of a policy blind-spot. We don’t see discussion or activism around energy depletion in the same way we do around issues like climate change or child poverty. But that won’t make it go away – if anything it should redouble our commitment to a transition away from fossil fuels.

However there is a hard truth to be swallowed here. While recent studies tell us that a global transition to 100% renewable electricity is feasible throughout the year and more cost effective than the current system, it’s hard to see us scaling up renewables in time, particularly if we’re not looking at the whole picture. With risks like this, now is certainly the time for a more open approach on our energy situation.

Edward Miller is a trade unionist

‘Why is it ok to frack Taranaki if we’re going carbon neutral?

Because we are not going ‘carbon neutral’ -the government is just pretending. And NZ is desperate for energy.

Peak Oil never went away; the global economic system is now propped up by fracking and other short-lived desperation measures that add to environmental stress and add to planetary overheating.

100% Athur & AFEWKNOWTHETRUTH

We needed to lead by example and this is not an example of “zero carbon activity is it as the intangibles cancall out any ‘clean burning’ of gas, because the transportation and fracturing using chemicals cancels out any stated ‘positives’.

‘Smoke & mirrors’ from Jacinda here sadly.

If climate change is NZ’s “nuclear free moment”, Jacinda should be using her new found popularity and respect overseas to push for anti AGW action as hard as she can at overseas fora. However, whatever she does will not carry much weight unless NZ is seen to be doing everything it can to mitigate climate change. Fracking, from that point of view, seems counterproductive.

Perhaps they should change the law to make it a government decision rather than an administrative one.

“Recently PM Jacinda Ardern moderated her statements about climate change being our generation’s nuclear free moment, noting that the public just wasn’t unified on this issue.”

Surely, JA new this 18 months ago. I’m constantly having to battle with man-made climate change deniers

The public doesn’t have to be unified. The government has to show leadership and grow a pair.

Although Fracking is not a new technology, it is basically untested over time and highly controversial; directly associated to higher methane emissions, subsequently contributing to accumulation of greenhouse gases and related climatic events.

How can the allocation of 2200 square kilometers of land around Taranaki just be an administrative decision?!

?!

The analysis of Edward Miller shares some very interesting observations that would certainly justify further investigation and clarification:

• “Bizarrely, fracking didn’t get a mention in the Ministry for the Environment ‘Environment Aotearoa 2019’ report, which clearly identifies climate change as one of its major themes.”

?!

• “In particular, fracking’s methane emissions are much higher than conventional extraction, which brings us back to the Government’s split gas approach (through the recently introduced 0-Carbon legislation): these gases have a longer phase-out period under the proposed law, meaning that it’s possible to still reach the targets set under the proposed legislation.”

?!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kfx80H3N1g

Physical risks and concerns of Fracking:

• Contamination of groundwater

• Methane pollution and its impact on climate change

• Air pollution impacts

• Exposure to toxic chemicals

• Blowouts due to gas explosion

• Waste disposal

• Large volume water use

• Fracking-induced earthquakes

• Workplace safety

• Infrastructure degradation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dEB_Wwe-uBM

‘The Shale Boom Is About To Go Bust’

https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/The-Shale-Boom-Is-About-To-Go-Bust.html

Whereabouts in Taranaki are they going to track?

Comments are closed.