On the panel on a sustainable world at the hui in October 2018 on What an Alternative and Progressive Trade Strategy for New Zealand, Aroha Mead, from Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou, reminded us what it means to live in Aotearoa.

Aroha is chair emeritus of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy and has recently been appointed to the advisory board of Fonterra.

[He mihi]. I am going to take us into a very different space and come back to some of the issues you have been hearing since the beginning when Ngati Whatua welcomed us here. You have seen there remains some fundamental issues of a constitutional nature that have yet to be resolved in Aotearoa in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi and the rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga of hapu and iwi over their taonga, the treasures inherited from the ancestors. These treasures include not just lands and waters, but landscapes and ecosystems and species and the genetic resources, as well as a very rich cultural heritage that includes a knowledge system about the environment and the interaction of people with the environment that is deeply embedded in inter-generational wisdom and values and practices.

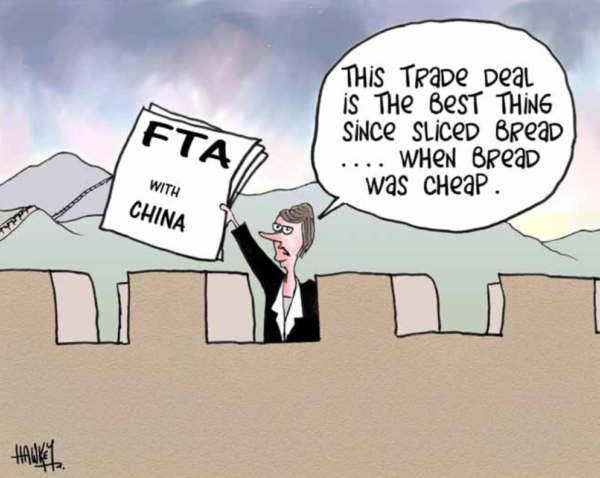

Until such time that these fundamental issues are satisfactorily worked through there will always be an underlying scepticism about the promises of global trade. And when the Crown says that it has a priority to protect and enhance national interests as a bottom line in the various trade agreements it enters into, we can’t help but have reservations about who is actually included in the national interest. We can’t see ourselves in there. Because if there is no agreement at the national level about hapu and iwi have kaitiakitanga over their taonga tuku iho then there is a high risk that Maori rights and interests will be eroded rather than enhanced through trade agreements.

In 1999 you may have heard of the Wai 262 claim, the number of the claim with the Waitangi Tribunal. The claim is known as the indigenous flora and fauna claim. The claimants sought confirmation of Maori rights and interests through Article 2 of the Treaty. The Tribunal conducted two sets of hearings and after 19 years in the system finally released their report, Ko Aotearoa Tenei, in 2011. And 8 years later we are still waiting for the Crown to respond to the report. The Wai 262 claim challenged the colonial culture of asserting ownership over everything and anything. Not just Maori land, but also native flora and fauna. This colonial culture uses legislation to assert ownership, and be very aggressive about ownership, almost treating it as a hoarder collecting and collecting and dumping somewhere with no order to it, no structure to it.

We would argue that the same attention that the Crown has put into claiming ownership has not ever been paid to the duty of care, caring for what it has assumed ownership of. As a result in the latest report over 4000 indigenous peoples are threatened or at threat of extinction. Put another way, between 2010 and 2016 nearly 80% of our birds, bats, reptiles and frogs are classified as at risk of extinction or highly threatened. Our rivers are degraded. According to the Ministry for the Environment Our Land 2008 report 192 million tonnes of soil was lost through erosion. I recently saw a video that my whanaunga from Ngati Porou put out of going deep into the heartland of the Raukumara ranges. You would expect in the heart of these native forests to hear all the birds and have thick undergrowth. Two days into tramping and the undergrowth was all gone. You could just walk through the forest and there was nothing there. No sound of birds. That’s the kind of care the Crown has given to what it says it owns.

What I have always found as a really unusual and puzzling dynamic in NZ is that many who are committed to the environment, even though they know how much harm is being caused through neglect by government, they still would rather have that than have lands returned to Maori. They will do anything but actually return the lands to Maori. And even though we have had some quite innovative Treaty settlements – we have had part of our nature become legal personality, we have co-governance, we have co-management, we have everything on the table except the return to Maori outright of the right to make decisions. Part of that comes from this fear that Maori will somehow do exactly what the Crown has done, which is regulate, not allow access, and perhaps further diminish.

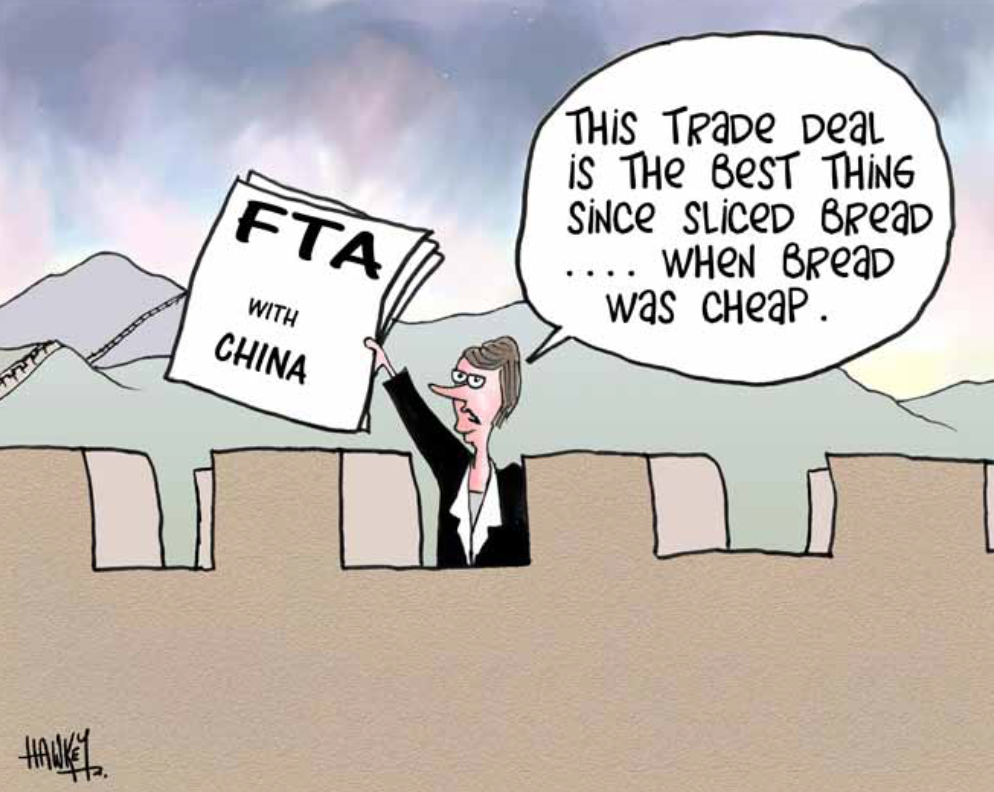

For me, a progressive future is one where people have more trust that Maori as tangata whenua actually have the best interests of the environment and the richness of this country at heart. The harm that’s been caused wasn’t a century ago, or during the time of the moa that is constantly dragged up. These were quite recent. These are poor policies and poor decisions that are being made right now. And Maori cultural expressions are still being appropriated by overseas companies, including companies that NZ has free trade agreements with.

I just want to come back to my initial point that until such time as government has the very discussions with Maori that it has been steadfastly avoiding – the constitutional status of the Treaty, tino rangatiratanga of hapu and iwi, responding to all of the issues raised through Wai 262 – the scepticism of government to adequately factor Maori interests will remain. And I also want to say to this concept of a global citizen. While I can relate to it as in terms of a global community of people, I think the fundamental issue of your identity as a tangata whenua person belonging to a land is of such paramount importance to making wise decisions that I wouldn’t want to see this leap into global, because the whole part of being local is that it makes you make wise decisions to protect the resources.

Barry Coates (chair): Perhaps a counter-point of the global identity is a greater connection of indigenous peoples around defining those rights and restoring those rights. To what degree do you think that has power as a concept, or is it necessary to struggle on a country or iwi by iwi basis?

Aroha: That is not an easy question. What I am suggesting is more than an acceptance that Maori and indigenous peoples have rights and interests that should be protected. It is that the societies in which we live should also be comfortable with those values and trust them a little bit more, that wise decisions can be made by applying indigenous values. Especially around the environment, where the knowledge system of that interaction has existed and survived and been proven to be robust. It is there and able to offer some sound solutions to many of our problems. But it is being denied purely because it is indigenous.

Question from the floor. Climate change and inequality – we can’t address one without another. What changes do we need when we also look at social inequality as well?

Aroha: Any environmental issue has social dimensions. Displacement of indigenous peoples from their lands is an obvious example. But marginalisation of indigenous peoples from their lands has been a global phenomenon. It’s behind a lot of the poverty we are experiencing in the world. And although it might be complex, if we haven’t yet got the picture that you have to deal with the environment and culture and social and economic factors all together at the same time then you are going to inevitably repeat the mistakes of the past and only deal with one fraction. We need policies that can go across all of them.

People are always impacted upon by decisions. Let’s just take it as given that every decision has a social dimension. When we are talking about resources, and there are indigenous peoples in those countries, it’s also going to impact on them, that’s a given. We have to fundamentally change the intellectual framework we use to analyse things. I always found it amazing that it took until 1992 for the governments of the world to acknowledge there was a link between environment and development. That’s pathetic. Since then the link was acknowledged they have carried on as if you can separate the two. We will not change the environmental degradation or eradicate poverty or deal with any of the other millennium development goals or the new sustainable development goals, without bringing all these elements together.