I awoke early on my first day in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to catch the women walking to work in droves. I must have seen thousands, not a child between them, all walking stoically toward the fenced factory doors, their brightly coloured dresses and scarves surreal in the bleak grey surroundings.

It’s been just over a month since an upmarket New Zealand designer, Denise le Strange Corbett, was caught selling shirts from Bangladesh as New Zealand made. She explained away the fraud by claiming it was just the labels that were made in New Zealand. She went on to say that the factories in Bangladesh where the shirts come from, were made in factories where the workers had the same conditions as workers in New Zealand.

It’s been just over a month since I claimed she was wrong. It’s been 4 days since I arrived in Dhaka to prove my point.

My host while in Dhaka was Amirul Haque Amin, General Secretary of The National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF), a union that represents over 80,000 workers. Amin happily furnished me with the facts before dispatching me out into the Dhaka traffic madness to visits factories and meet workers. The garment industry is vast. It employs more than 4.2 million workers, 85% of whom are women. There are more than 5,500 factories.

As I read through the laws I started to think that maybe I was wrong. Maybe it was me who had a Eurocentric worldview and couldn’t accept that things were actually all tickety boo. That would suit many peoples world view, especially those people with a passion for fashion. According to local employment law people are paid a salary calculated monthly and after normal work hours can expect overtime which should be paid at twice the normal rate. Workers are entitled to at least one day off each week, casual leave for 10 days, earned leave of 18 days, annual leave of 18-20 days and of course maternity leave of four months on full pay which is going to be significant if 85% of your work force are women. It sounds fair, generous even, there were even 11 days allotted for festival leave. Perhaps I would not be a fashion passion killer after all?

My first factory visit was to Dica-Tec in the suburb of Ashila. A German/Bengali partnership that employs 1,200 workers over five floors. The factory was beautiful; open, breezy, clean, and everyone was wearing protective masks. The women were decked out in a plethora of colour, a flurry of floaty fabric perpetually in motion like an industrial Monet. I was encouraged to walk the floor and take photos. I insisted on asking permission from the workers before taking photos much to the amusement of the general manager. “They only work nine hours per day and they get a full ½ hour break,” he said. I asked about over time and he assured me they got paid for that too, they did two hours overtime a day. So they actually worked 11 hours each day with ½ an hour break. A small white lie that signalled a bright red flag in the field of colour.

Factory 1: Dica-Tec

The second factory, Multiple Fashion Ltd, was older and nobody was wearing masks. It employs a mere 700 workers. The machines were old, it was hotter, they showed me a sick bay with a doctor – okay he wasn’t an actual doctor – I confirmed this by asking if he could write me a script. More like a first-aider. In hindsight I think he may have just been some guy. The thinly veiled attempt to show off world class working conditions was beginning to fail.

Factory 2: Multiple fashion

Over the following evenings I was able to speak to workers without the watchful eye of employers at local branch offices of the NGWF. In all I would have spoken to more than 80 workers. The workers were from many different factories. They create the clothing for H & M, Zara, Max and Kmart among others. Almost every worker I interviewed had worked on H & M clothing. The following is a synopsis of what the workers told me, and each point was backed up by at least one other worker.

When there are visitors to the factory, the owners tell the women what to wear or provide the clothing. Several women spoke of factories where they rented children for the day and turned a room into a crèche. I only heard of one factory that actually provided childcare. This went someway to explain the lack of children on the streets in the morning. They did the same with sick-bay rooms, creating mock health centres when visitors, especially buyers, were expected.

They work anything from 11- 21 hours a day, the average being 16 hours. They get one break of ½ an hour or an hour, depending on the factory. Overtime is not voluntary. You work the hours requested. You stay till the orders are filled. There is huge pressure placed on everyone to meet the production targets.

The women are routinely verbally and physically abused. Examples of this behaviour, and there were many, include yelling, slapping, pushing and humiliation. ‘Beating’, said a couple of workers,

‘We get beaten and we get punished.’ I asked what punishment was and this is one of the examples they gave; a woman forgot to change her outside footwear to indoor so the supervisor bound the shoes to the workers head and then paraded her around the factory floor while pushing her and mocking her, telling everyone how useless she was.

They aren’t allowed to talk to each other. Talking slows hands. If you have time to talk you should be sewing faster. Everyone is so busy, the one thing there is no time for is checking IDs. Several people knew of underage workers – it is not as common as it used to be but it still occurs.

If workers are sick they simply lose pay. They just take their money. Not that they routinely pay them correctly anyway. They don’t record overtime. If these women want to take a holiday day then they work late the entire week before. Some factories only allow one day off a month, some none. If they complain, they get fired. If they are sick they get fired. If they are old, they get fired. If they get pregnant they need to conceal it as long as possible, otherwise management will just keep increasing the person’s production targets so they start to fail, and then they fire them anyway. These are the conditions your clothes were likely made of.

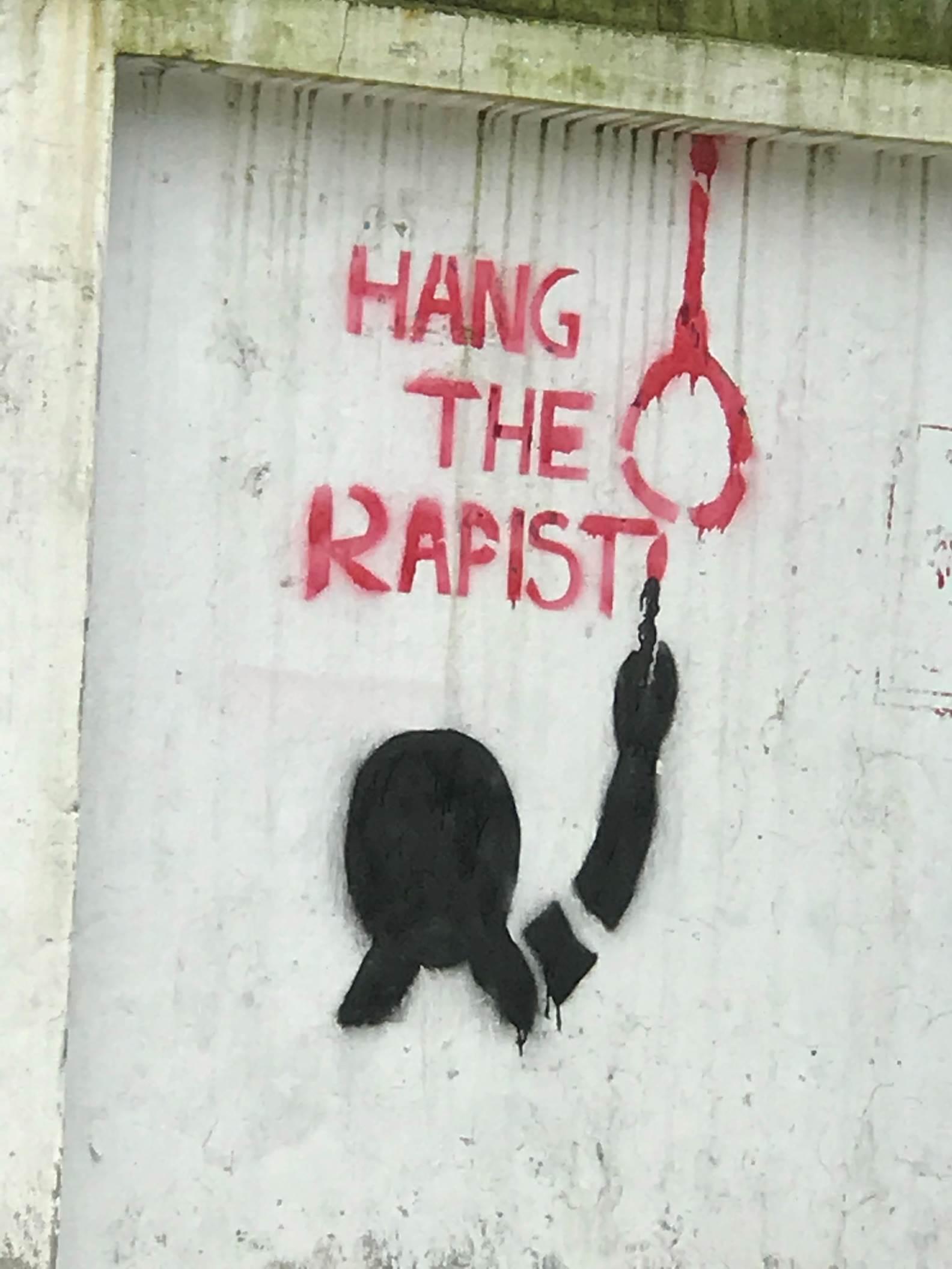

Then at the end of the shift they walk home. I asked if it was safe. They looked nervously at each other then all talk at once. It is safe if you have someone to meet you, or walk in groups, but when you have no one it is not. There have been assaults. Attacks. Rape. Most of them can’t afford to live to close to the factories because rent is too expensive. Most of them walk for around an hour to get home.

When I went to finish the interviews I asked the woman what they wanted to change. What would make their lives better? More pay was rapidly followed with less abuse. They just want people to stop harassing, hitting, and belittling them. Their pay varied from Tk 5000 to Tk 7000 ($85-$120 NZD per month). Many get less than the legal minimum.

Graffiti in Dhaka

Then after working all day, meeting with me at night, some of the women kindly offered to take me home and show me where they lived. The following day we drove from the main roads, to the side roads, down alleys. We were still in downtown Dhaka and yet a world apart. A world where they have never heard of World Fashion.

My first visit was with Kulsum. She rents two rooms. The two rooms are home to her, her sister, two young brothers, her baby, and her mother. Six people in two rooms the size of my office and bathroom combined. She has lived in the slum for 25 years. Almost her entire life. Both she and her sister work in the factories. Their income provides for the entire family. The rent on the tin shacks is Tk 5000. Almost her entire wage, leaving what her sister earns for everything else the six of them need to survive.

Kulsu, her sister and her family.

Then I squeezed down some more alleys, ankle deep in mud, to visit Rani. She also rents two rooms – one for her, her husband and child, and another for her sister and brother in law, and their children.

There is no running water. There are four shared latrines for 15-20 families. In the morning there are queues. She has lived here for 15 years.

We sit for a bit and talk. These women are in some ways lucky. They have their children with them. They see them at the end of each day. Many of the other women leave their children in remote villages and will go up to a year without seeing them. I spoke to those women too. So many women I wish you could meet them all. As we sat, Kulsums mother who was cooking on the floor beside us offered me dinner.

Top Rani, her son and her sister and in the room next door her brother and sister in-law.

As we drove back to my hotel it started to rain. Outside I watched the streams of women walking along the road, too poor for even a rickshaw. They smile and laugh, still eye catching in the vivid colours that brighten the bleak streets. It is so easy for us to romanticise them, fetishise them – these beautiful and exotic workers. But you don’t need to look too closely to see that their saris are soaked, their hands full of scars, and their shoulders are sagging with exhaustion from the hours and hours they pour into their work, for the lives they sacrifice so we can have a few dollars off. In the case of World Fashion you don’t even get the savings. It makes it all the more horrific. The sweatshops that emerged from the late 1900s have not disappeared, as much as we all would like to think. These companies have not spent years perfecting the craft of garment-making; they have spent years perfecting the craft of concealing slave labour and it’s worlds apart from what the rest of the Western World imagines. You don’t have to look hard, you just need to bother to look.

That’s grim Kate, but not buying from Bangladesh would remove what meagre income these people do have have wouldn’t it ? It does make it impossible for NZ domestic factories to compete. There’s a complex moral conundrum here. Should we look after NZ workers at a decent level, or should we allow them to be redundant in order to allow Bangladesh workers to survive? I think that Bangladesh’s problems are outside of the scope or capacity of New Zealand to remedy, and we should attend to the welfare of our own people for whom we are responsible and do have the capacity to look after.

D J S

There is a much better strategy than changing where we shop as individuals and it’s been done before: Target one brand (that sells in the western world) with bad publicity and a boycott, tell them the campaign will stop when independent auditors confirm they meet acceptable standards. When they cave in, which they usually do, move on to the next brand.

“not buying from Bangladesh would remove what meagre income these people do have wouldn’t it”

We don’t know that.

Perhaps if the employers were told we wont buy their good while they treat workers so appallingly things may change. So we have to tell KMart we wont buy goods imported from these employers.

Which means we all have to.

But most wont because their life here in the ‘wonderful’ New

Zealand is so difficult they have little energy to fight for Bangaldeshi women.

Hi David, at no point do I suggest a boycott. I am writing two more blogs and the last one will include my thoughts on how best to support the worker from a trade union perspective.

From an environmental perspective the entire industry is unsustainable. At some point we will have to confront our wanton consumerism.

The cheap bargains always come with invisible baggage.

But honestly, in a country where nearly half the population vote for a political party that uses its police force to harass political opponents, can we expect anyone in sleepy hobbit land to care a f… about worker exploitation in Asia, in Africa, in anywhere?

Sadly, no.

Not if it means they have to pay a bit more for their undies and t-shirts.

Stories like this should be lead story in daily newspapers, on TV news and in Stuff (yeah right).

Very good article, I wish it would reach the attention of those in the world who could do something positive about it.

“Not if it means they have to pay a bit more for their undies and t-shirts.”

Sorry, Mike. Those items are pretty scarce at the op shops.

If it wasn’t for the underpaid in Bangladesh and China and other places the underpaid in NZ wouldn’t be able to afford even half-way decent clothing.

And it doesn’t last. It often can’t be passed along to the next size down because the elastic has gone, the colours have faded, the seams have given up.

It’s bad at both ends of the chain.

Comments are closed.