“Aspirations might be similar, but culture, the makeup of the whanau, hui, beliefs, language, marae, it’s all very different to the dog-eat-dog individualistic capitalist Pākehā model.” Were those the words of an indigenist Māori thinker? No; in fact, they were the words of television presenter and relatively liberal-centrist yarn-spinner Duncan Garner on the subject of building a new prison run on kaupapa Māori, or Māori values. Rachel Smalley, another presenter, also agrees. It is an idea that the political wing of the Iwi Leaders Group, the Māori Party, was the first to advance, closely followed by the Labour Party (although this has been subsequently retracted by leader Andrew Little). After all, Māori are drastically overrepresented in crime and imprisonment statistics; something like 55-56% when they constitute around 15% of New Zealand’s population. The disproportionality is only increasing, despite the fact that the Māori Party, which we would expect to be a strong lobby group on this matter, has lent its support to the current government for nine years. But it has been insisted by Kelvin Davis that the new prison won’t just be for Māori prisoners; it’ll be for everybody. A lot of ‘progressive’ minded people seem to be charmed by this idea. But some, including Garner and Smalley, write as if Māori prisons were only for Māori prisoners. Regardless, having a Māori prison would at any rate allow the culturalist vision of social policy to be tested. But there are still some questions that remain unanswered. What would a ‘kaupapa Māori prison’ actually change about a prison? Indeed, what does ‘kaupapa Māori’ mean to the proponents of this idea?

It has become fashionable in some quarters of the Left to, in the way Duncan Garner has, contrast an apparently universally applied ‘individualistic’ culture of European or Anglo-Saxon peoples with a ‘communal’ culture of indigenous peoples (Māori and Pasifika in this country). This binary applies no matter whether real Anglo-Saxon or Māori people actually behave differently or not, so much so that people now describe that penchant for individualism or collectivism as if it were an essence inherent to a particular group. This discourse serves a very simple – and really rather patronising – function. It implies that Anglo-Saxon culture is inherently opposed to reciprocity, family and inner spirituality, whilst Māori culture is presented as free from the corrupting individualism and materialism.

If this sounds familiar, it is because such a formulation almost exactly maps onto the colonial stereotype of Māori as a wholly different, rural, spiritualist, naturalistic ‘Other’. What has changed from colonial times is the valence of this characterisation. Māori culture today is purified of any real ‘bad’ elements whilst Pākehā culture embodies only bad elements. Not only does this way of thinking revive Romantic notions of the ‘noble savage’, or ‘natives’ as ‘closer to nature’, it universalises the current experience of Māori regardless of expressive they are of this ethos or whether they are materially alienated from the wider society. In other words, Duncan Garner obscures the concrete, material status of different groups of both Māori and Anglo-Saxon people by reducing each to a ‘cultural’ identity whereby Pākehā equals rapacious capitalist and Māori equals nativist non-capitalist. Needless to say, this strange, mystifying talk does very little for Māori or for anyone in prison, yet it is this imaginary antagonism that is behind the debate, indeed, the very idea, of a ‘Māori prison’.

It is also clear that, like the binary culture formation, ‘kaupapa Māori’ is also a politically contested term. No Pride in Prisons, an activist group quick to oppose the new prison idea, disagrees with the Māori Party and Labour, alleging that prisons and kaupapa Māori are incompatible. Indeed, No Pride in Prisons have the upper hand on this over the politicians. Emilie Rākete, the group’s press spokesperson, correctly claims that prisons did not exist in traditional Māori societies and that from a historical point of view, prisons are in fact not compatible with any tikanga, or customs, of justice. What is important to remember in this debate that prisons are directly related to the often irreparable psychosocial and material damages done to their denizens; the effects of which reproduce across generations. If this intergenerational harm principle is caused by the structural character of the prison itself, it is not clear what a Māori-values prison can do about it. I myself am not convinced in the slightest that the politicians’ conception of “Māori values” (which they seem to have trouble elaborating on in public discussion), when applied to the prison, will result in anything truly that different from the existing corrections systems.

The Māori Party and Labour/Kelvin Davis have a clearly different idea of kaupapa Māori as they believe it can be subsumed into the prison system. In a Māori prison, Duncan Garner has been told, prisoners would learn their language, customs, and pēpeha (origins), and be able to meet their whanau. This might be good, Garner says, because prisoners often have no role models other than gangs and abusive parents. However, plenty of questions arise just from Garner’s description. What of those who are alienated from any family or have no family left (one in five Māori report zero tribal affiliation, and many other affiliates themselves have little connection to the tribal structure)? How would this help address the long-lasting social harms and stigmas that come from having been an inmate, even for a very short time? How would they be able to meet and having meaningful relationships with whanau from inside a prison? Why would prisoners want to meet whanau if they were abusive, as Garner alludes to? Garner & co. also fail to address the actual fact of the matter – and this is the big smackdown against the idea of the Māori prison even having an effect – that the Department of Corrections have already been administering programmes ostensibly based on kaupapa Māori, like the Tirohanga initiative, since 1997. Kaupapa Māori programmes from within prison have essentially reached their 20th anniversary. The consequence of such programmes is the depoliticising of prisons by recoding an entrenched social deficit into a cultural one. The implication is that prisoners are lacking in ‘culture’. As Rākete says, “teaching waiata to prisoners does nothing whatsoever to address the real causes of imprisonment.”

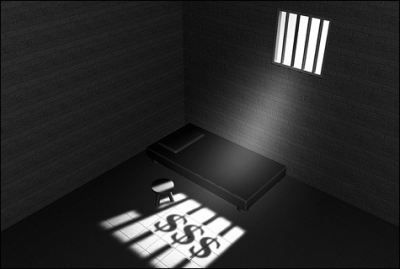

What are those “real causes”? Crime occurs for a multiplicity of reasons, but the overwhelming majority of prisoners in New Zealand stem from conditions of socioeconomic poverty, ontological insecurity, and psychosocial torment. It is a truism to say that crime causes harm and harm is bad, but it does not necessarily follow that such harm must be punished by being locked in a cell with other people who have done harm. Even the most threatening, violent, drug-addicted individuals deserve a chance. These groups are socially and economically alienated, and if any prisoner had an OK life before they went into prison, the chances are that afterward they will be just as lost and rejected as the rest. There is a consensus in criminological research that handing down official sentences actually increases recidivism. It is rehabilitation and human service provision that actually works best for prisoners – this is a fact that has simply proven unsavoury for politicians of all currently relevant parties, who often like to boast about how ‘tough on crime’ they are – this includes Labour, as this more and more appears to be the main line it is taking to the election.

We cannot wax lyrical on the problem here. Māori have suffered from a project of colonial domination that entrenched an imperial government and set about expropriating land, natural resources, and precious landscapes in order to repurpose their materials into goods to be circulated in a profit-motored capitalist economy. To that end, Māori overpopulate the lower rungs of class society because that is where they started, and we know that capitalist society, being anti-meritocratic, entrenches the overarching majority in their social positions of origin. There is a correlation, and very often an exact causal link, between the antecedents of this material situation, racism, and lack of opportunity, and a Māori person (often man) being sent to prison.

Duncan Garner thought he was being progressive ‘for once’ on a ‘Māori issue’, but in fact, he has lent support to one of the worst ideas for Māori that have been dreamt up in the world of politics. To be frank, the solution proposed by the Māori Party and Labour is a coup de grace for any prospective plans or commitments of theirs to ending the plight of Māori prisoners. It is an affirmation that the prison is a natural site of justice and a reinforcement of the ethic of vengeful punishment that scours societies all over the world. New Zealand’s incarceration rate, like Canada’s, Australia’s, and the United States’, is just embarrassing, and to top it all off wastes billions of dollars of taxpayer money every year. The Māori Party, who have supported the current government for nine years; the government that passed the Bail Amendment Act and has run the corrections budget broke from the new influx of prisoners, have presided over a worsening of this problem. Neither them nor Labour can be trusted to do anything on this issue. There is little political will or discussion for non-prison rehabilitation. Bill English was admittedly right when, before he became Prime Minister, he said prisons are a “moral and fiscal failure”, but it seems those were just empty words; since he became Prime Minister he has done absolutely nothing to alleviate the situation. He has done nothing, and Māori families tormented by the spectre of the prison stand to gain nothing, from idle cultural politicking. It is past time to start to think about and eventually realise a country, perhaps a world, without prisons.

Alex Birchall is a researcher and postgraduate student in sociology. Born in Whangarei, his family hails from the north of New Zealand and Rotuma (Fiji). He is currently researching the limits of current housing policy in Auckland. Alex’s academic interests include: Marxism, the politics of racial ideology and nationalism, the philosophy of social science, the politics of globalisation, and the sociology of knowledge and education. His work has been published in New Zealand Sociology and sonic art journal Writing Around Sound. He identifies as a ‘left communist’ and a ‘critical Leninist’.

Excellent blog Alex.

I think the three things we need to alleviate this burgeoning problem are…

1) proper investment

2) proper investment

3) proper investment

Unfortunately we, as a society, are not prepared to do this.

The vast majority will not vote for such investment.

The current talkfest will continue, the band aids won’t work and the problems will escalate as the prisons keep releasing people who have no chance of surviving out there….

No prisons = no capitalism.

Having been a teacher for 13 years,and part of this specialising in remedial education I have a fair idea of what is required educationally.And as a follow on there needs to be an apprentice/skill learning program that enables a prisoner to equip himself to earning a living. All this is not going to happen in the grim environment of our current prisons.So this needs to change. Prison needs to be a place that the prisoner wants to go to because it will solve the problems that got him imprisoned in the first place.Substance abuse needs to be treated as a condition to be treated, like alcoholism.And there needs to be jobs available to all who are able,conferring dignity and a sense of belonging to a community.So the real problem is the unwillingness of society to invest in structures that will solve the problem once and for all.The resources already exist.They are in places like our Armed Forces.Who is attacking Us? All we have ever done in the last 100 years is attack countries on the other side of the world.That has actually only made us less safe.That would free up the 20 billion dollars the National Govt intends to use on military hardware. Lets instead fight a war on poverty,on incarceration, on rectifying the ills of our society,so N.Z can become an example of what a truly decent society looks Like!!!

I agree that merely teaching kapa haka to downtrodden kiwis of Māori heritage is not going to magically change the material conditions in which crime and punishment occur, nor those people’s psycho-social response to those conditions. But in the context of Davis’s suggestion, this is a strawman. As evidenced by the fact that the “Māori prison” would be for people of any ethnicity, clearly this is not an idea based on using traditional entertainments to stimulate mythical tikanga genetics in people of Māori whakapapa. It’s more like a suggestion of a different cultural vantage point from which to rethink the goals and practices of criminal justice from first principles.

“There is little political will or discussion for non-prison rehabilitation.”

Perhaps this is why the concept of a “Māori prison” has been raised? If a compulsory residential rehabilitation program for people convicted of doing harm to others was actually run according to any kind of functioning tikanga (whether a generalized “kaupapa Māori” or tikanga specific to an iwi/ hapū), it would be a “prison” in name only. In practice, it would be more like compulsory treatment in a mental health facility, except in this case a *social* health treatment facility.

Imagine a system that actually restores justice, rather than merely taking its revenge on those who engage in disorderly, anti-social behaviour. Much that prison abolitionists want could be achieved in this model, and yet the concerns of those who fear violent crime or the invasion of their homes could, perhaps, finally be addressed too.

In dismissing the suggestion so glibly, Alex engages in a classic progressive assimilation argument that is part and parcel of “noble savage” colonial thinking. It’s for the good of Māori themselves, the thinking goes, that any suggestion of cultural distinctiveness be written off as mythology, and any individual of Māori ethnicity simply be treated as a brown Pākeha. The idea that it might be beneficial to Pākeha to attempt to assimilate ourselves into local Māori ways of being, rather than continuing the failed attempts to assimilate Māori into imported British ways of being (dysfunctional agriculture unsuited to the geography, backwards calendar, punishment based justice etc), never even enters the discussion. It’s about time it did.

This comment is ridiculous. I did nothing of the sort. The political use of kaupapa Maori is mythological because kaupapa Maori has nothing to do with prisons. It is essentially the same argument as what the Maori caucus from No Pride in Prisons has put forward; are they ‘assimilationists’ too?

I don’t think Strypey read, or in any case understood, your excellent argument, Alex. Keep up the good work! It is so refreshing to see real critical engagement with these issues in amongst the tide of wishy-washy, lack-lustre pseudo-liberalism.

I broadly agree with Alex.

The Maori Party stands for the iwi leaders forum.

They have appropriated Maori ‘culture’ as a cover for building Maori capitalism.

This puts them in the same camp as the main capitalist parties.

It is not surprising to see Davis stake a claim for Labour since they are competing with the Maori party for the Maori leadership.

So ‘Maori jails’ run by iwi are just a cover to grab 15% of NZ capitalism.

Strypey thinks no doubt that “No Pride in Prisons” not to mention open Maori communists are part of ‘noble savage’ neo-colonial thinking.

On a practical note, if the present justice system does not help much to rehabilitate or reduce reoffending, then why not try any Maori alternative justice system?

It would have to be better than what happens now.

Comments are closed.