Deep in the basement, in the East wing of London’s impressive Somerset House, an important exhibition is drawing a small but steady number of visitors.

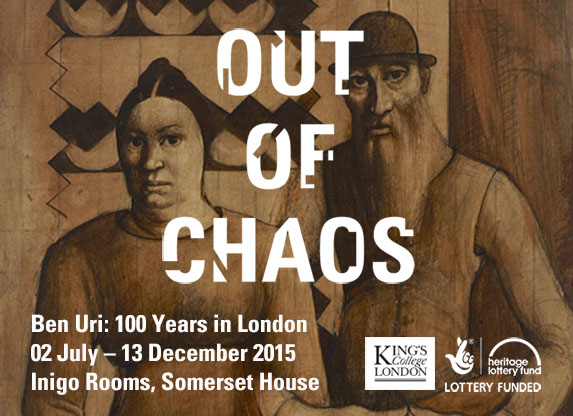

“Out of Chaos” celebrates the centenary of Ben Uri Galley and Museum. Ben Uri’s origins can be traced back to 1915 when an art society was founded in Whitechapel area of London.

Today, Ben Uri is the only specialist art museum in Europe that aims to communicate the experiences of forced migration and identity through the visual arts’ lens. “Out of Chaos” explores the formative history of Ben Uri, its experiences through both world wars, and it’s future role in driving debate around the central issues of migration and identity.

As an almost perpetual immigrant, grappling with my own sense of identity and belonging, I made my way to the exhibition not entirely sure what to expect.

The impact of the visit has left me in a haze of emotions that has not faded since.

Although the collection is predominantly based on Jewish artists and their experience of persecution during Nazi Germany, it is clear that the immigration experience has a universal story to it: the cultural difference yet the yearning to belong, the struggle for integration and the rootlessness are all themes that I, with my non-Jewish, Middle-Eastern background, can readily identify with.

The first exhibit that greets me is familiar and evocative.

The Sabbath Rest by Samuel Hirszenberg (1894) shows members of three generations, including a bedridden elderly, gathered in a humble room to keep the Sabbath. The youngest member of the family is reading from a letter. The glimpse of the view outside, through a small window, is one of industrialization; its modernity and promise of riches are at sharp contrast with the poverty and piety depicted so masterfully inside the room.

The younger members of the family are positioned near the window; they clearly feel safe and connected with the outside world where the promise of a brighter future draws them closer to the host culture.

The same cannot be said for the older family members whose sense of exile and alienation are palpable. They sit in the darker corners of the room in contemplation and somber reflection.

What chaos brought them here? What sacrifices did they have to make? What fears do they have for the future?

Hirszenberg’s work transported me to Gothenburg, the city where three generations of my own close relatives have migrated to, and where I went last year to visit my beloved Aunt Simin before she passed away.

Simin was bedridden, just like the matriarch in Hirzenberg’s painting, and although she lived a privileged life, her life in diaspora was always filled with longings for her beloved hometown of Shiraz in Iran.

The little Swedish that Simin had painstakingly learnt so late in her life, had completely escaped her.

In her last years, she thought and talked about little else but the rose-scented Persian gardens, the classic poetry of Saadi and Hafez, the warm sun that covered Shiraz in its glow, the beautiful folklore songs that nourished the souls, and, most of all, of family gatherings that were filled with love, warmth, acceptance and belonging.

She spoke to her lovely but completely bewildered Swedish carers in Farsi; she asked them if they knew what spiritual joy Shiraz could evoke in one’s soul “ Shiraz che safai dareh..”.

Today’s Shiraz bears little resemblance to the glorious memories that my Aunt Simin treasured and relived so often in her head; but the fact that she had those memories sustained her and elevated her until her last day came to a gentle end.

Now, the younger members of the family she has left behind are dotted around Europe and America; bicultural, multilingual, highly educated, ambitious, different but integrated, they are all contributing to their adopted counties. That is the immigration story.

Another work by the Polish-Jewish painter, Joseph Herman is simply titled “ Refugees” (c. 1941). The work was produced in my birth-town of Glasgow where, like Herman, I found refuge after leaving the post-revolutionary Iran.

At the center of the painting, is a father with a mattress rolled under his arm. He is standing anxiously next to his wife who is clutching a small baby with a little girl clinging to her leg.

The expressions on the family’s faces and the use of dark blue and black colours convey a sense of horror. The presence of an enormous black cat carrying a bleeding mouse in the background symbolizes the fate of those left behind; it also conveys the loss of control and the refugees’ feeling of being hunted, always on the run, on a forced journey to the unknown.

Here again, we find universality in the story of refugees, be they modern refugees fleeing from Syria, Libya, Eritrea or any of the 20 million Europeans whose Polish ancestry share Herman’s experience of displacement. The story is of forced migration due to war, political or religious persecution, dictatorship, and oppression.

As I stand witnessing the pain and suffering of the past European refugees (60 millions of them after the devastation of the Second World War) I ponder if today’s wealthiest continent in the world by far, has forgotten its past and the need to honour the fundamental right to asylum.

French Protestants were forced to flee from France in the 17th century.

Jews, Roma and many others fled from horrors of Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s.

Spanish republicans, Hungarian revolutionaries, Czech, Slovak and Yugoslavian citizens were all forced to flee from their homes. Nearly everyone in Europe comes from a refugee ancestry.

The impressive Ben Uri collection is, not only an excellent eyewitness to the émigré story, but also a testament to the contribution and achievement of those who come from distinct cultures.

In London, where more than 37% of people are born outside of the UK, Ben Uri needs to build on its impressive collection to include, as Jackie Wullschlager says:

“…the story of the Palestinian diaspora, of the Arab Image Foundation, of Jewish-Arab co-operative projects. If Ben Uri seizes such provocative opportunities, it will truly become a must-see museum for everyone…”

As the world is facing a refugee crisis, let us look to the art and its power to bear witness to horrors of the past. Let’s consider the contribution of those who were once regarded as outsiders but are now woven, so successfully, into the cultural fabric of their adopted countries. Let us be reminded of our own past and our responsibilities to offer refuge and stability to those who find themselves where once so many of our own ancestors found themselves in.

There is nothing to fear from refugees. What we should fear is our apathy towards the pain and suffering of others and the horrors that could follow from it.

Donna, what a wonderful exhibition to come across. I’m going to London early next year and it looks like I’m just going to miss it 🙁

As the grand daughter of WW2 Eastern European refugees and a mother born stateless I can relate well.

“Here again, we find universality in the story of refugees, be they modern refugees fleeing from Syria, Libya, Eritrea or any of the 20 million Europeans whose Polish ancestry share Herman’s experience of displacement. The story is of forced migration due to war, political or religious persecution, dictatorship, and oppression.

As I stand witnessing the pain and suffering of the past European refugees (60 millions of them after the devastation of the Second World War) I ponder if today’s wealthiest continent in the world by far, has forgotten its past and the need to honour the fundamental right to asylum.”

This current refugee crisis has affected my mother quite badly, especially the responses of most Western countries, and sadly the attitudes of many of the general public. They went to Australia, who didn’t want them because they weren’t British, but reluctently took Europeans that at least looked white and weren’t Jewish (so not a lot’s changed there, has it?) From my perspective, many of the 1st, 2nd generation decendents of WW2 refugees will be well aware of how the traumatic effects of the war still haven’t gone away, and in fact, have led to intergenerational trauma. So watching history repeat and knowing what will happen to these people in the long term, it’s heart-wrenching. Especially since PTSD is recgonised now and people stand a better chance of not having to suffer in silence and without help.

Whatever the solution, finding somewhere for refugees to go is just the start.

Dear Kay, you are right about the intergenerational trauma and the hear-wrentching suffering of the current refugees.

For your information, Ben Uri has a permeant gallery on 108a Boundary Road, off the famous Abbey Road in St John’s Wood in London. I hope you get the chance to visit on your trip next year and, like me, make a suggestion to the museum officials that this wonderful exhibition should expand beyond its current focus and deserves a permanent base in central London.

Thanks for that information Donna, I’ll do some research on his gallery. I’m only going to have a few days in London so will be quite time restrained; that particular exhibition I’d have made a point of seeing though.

Thank you Donna for sharing this with us.

Comments are closed.