We are starting to hear, again, more discussion about the ‘future of work’, and about robots taking over. This was a fashionable topic in the 1820s (the machinery question), the 1920s (automated production lines), and the early 1980s (computers). It’s a misguided concern, because its premise is that there will not be enough work for our workforce in the future.

It’s a bit like being concerned that we will not have enough pollution in future, and certainly more pollution creates more work; so, more pollution must be a good thing. Yeah right?

Work is unambiguously a cost (not a benefit), and we should never ever forget that. The real concern is the future of income, not the future of work.

In the late 1920s there was a substantial process of automation. A good example in New Zealand was the introduction of milking machines, and the migrations to the larger urban centres on account of less labour required on the farm. In Germany and the United States it was a time of huge investment in fixed capital, ramping up the global mass-production system just when markets for wage goods were collapsing. It was the era of Taylorism and Fordism; time and motion studies of workers doing repetitive tasks, and then assembly-line production.

Aggregate income, by definition, is the same as economic output. But we use the word ‘income’ most when we are emphasising the distribution of output rather than its composition. The really important concept, that of ‘wage goods’, captures both the idea of income and the idea of output. It was a commonly used phrase in the 1920s, rarely heard today.

In the early 1930s – the depression years – the world economy was ramped up to produce lots of wage goods, but workers’ earnings were so low (in large part because so many were unemployed or on short-time) that the market demand for wage goods collapsed. So, capital became as unemployed as labour was. Indeed Keynes was as concerned about unemployed factories and machines as he was about unemployed workers. Under these conditions, economic investment made no sense.

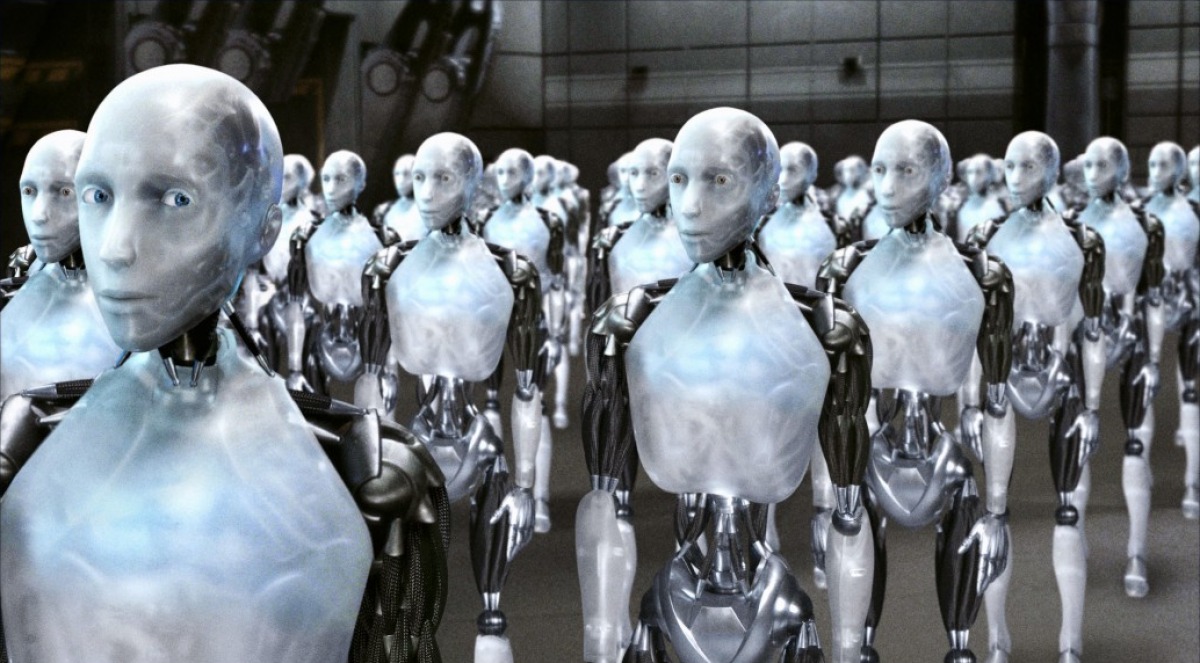

If, in the future, robots take over much of our work, then not only do workers stand to become unemployed, but so do robots.

The central structural crisis in the world economy today is that we have a productive structure based on pumping out masses of wage goods – ie the goods and services that wage workers buy – at a time when ordinary workers are paid too little to be able to afford them in the quantities we want to produce. At least Henry Ford understood that, if he was to create a great company and a great automobile industry, his own workers (and other workers like them) would need to be able and willing to buy automobiles. So he paid his workers more. Ford understood that, if the car was to have a great future, it would be as a wage good, not an elite good that only the rich would buy.

This system, where workers are not paid enough to buy the wage goods they make, may be called ‘scrooge capitalism’.

Debt is the short- and medium-term solution to scrooge capitalism; when the system requires the mass consumption of wage goods, but does not pay ordinary consumers sufficient income to buy them. If we won’t pay workers enough, we instead lend them the difference, so that the workers can buy the wage goods that the scrooge capitalists make. Indeed this system does work, so long as these capitalists never insist on the repayment of these credits. That can actually work for a long time, because it’s in the nature of scrooges that they do not wish to be repaid; rather they like to simply accumulate credits. (When one debtor repays a scrooge, the scrooge invariably looks for other debtors to lend to, rather than spending the repaid debt.)

Scrooge capitalism crashes when the scrooge capitalists stop lending to the communities of workers and to the workers’ communities. (We saw such a crash in 2008 with the temporary cessation of sub-prime lending.) Workers’ households must buy the wage goods; it’s central to industrial capitalism that they do so. Captains of industry live by making and selling wage goods. (The remaining rich mostly live by selling financial and business services to these industrialists, or by selling such services to each other.)

Is there another way? Yes, it involves distributing income in such a way that the ‘plebs’ – the 99% in recent parlance, but better thought of as the 75% – receive as of right bigger income shares than they presently do, despite this being a time when there is less need the labour.

So, if capitalism is to survive, the future of income has to involve a much more equitable distribution of aggregate income. It cannot be through higher payrolls, because wages are a cost to individual capitalists, just as labour is a cost to individual workers. (Capitalists, like workers, are cost minimisers.) What is required (in addition to present forms of income) is a return on collective equity; the recognition of the social need for a form of income that is more equal than wages.

By its very nature, private equity income is the most unequal form of income. Public equity income can compensate, by being the most equal form of income. Just as high wages helped Ford and his workers, public equity income can help today’s budding Fords sell their wares, can help ensure their workers are able to enjoy what capitalism offers, and can help those many people who are worse off than fulltime wage workers.

Further, once the plebs get a bigger share of the cake – both as an equity right and as a pragmatic means to maintain a market for the capitalists’ robots’ outputs – the working plebs can choose to work fewer hours, happily passing up the overtime (which I regard as anything more than 30 hours a week of wage work) to the robots and to the unemployed. The result can be substantial productivity gains, bearing in mind that labour productivity is total output divided by the total hours of labour supplied.

All society gains when we are able to choose to work less, while continuing to enjoy the same amounts of wage goods as before. Further it’s sustainable; the demographic transition to permanently low birth rates occurred in advanced and emerging economies once there was widespread income security. When we have income security, the production system responds to genuine consumer needs, rather than overloading us with the needs that its marketing machine requires of us. It’s no longer ‘profit or perish’.

In Economics 101, the production system (supply) is our servant, not our master. It can be so.

“is there another way? Yes, it involves distributing income in such a way that the ‘plebs’ – the 99% in recent parlance, but better thought of as the 75% – receive as of right bigger income shares than they presently do, despite this being a time when there is less need the labour.”

It is called “sharing the common wealth of a nation.” We had this in our previous era under Savage/Nash Kirk ect’ “egalitarianism” period.

We all need to belong and feel as a contributor to a society as our genes as a species dicate iit to us all.

To make us redundant will create anarchy and civil strife the world has never seen before.

I’ve thought about the sharing and contribution things a lot. Just a minor adjustment to the hours of the working week, with punitive taxes on the employer for “overtime” would make job sharing quite viable. It wouldn’t take much to deal with unemployment.

I think wealth and property taxes will be a given. The huge advantages they give must be recognised. That people will try to avoid them is also a given, but I don’t buy in to the idea that it would make them unworkable. I expect a few sent to jail as examples would get the rich in line pretty quickly.

Seems to me that the great fall down of this is that the ‘scrooge capitalist’s ‘ ie the superbanks, the IMF , the World Bank ….do not want to see this because of short term gain.

It would seem to me that Henry Ford was a cross point in world economics…he could well afford to indulge in that philanthropists view…although it was not only that but sheer pragmatism also.

The problem is with the scrooge capitalists…as we now find ourselves up against an entrenched neo liberalism – thought not that different from the Lassez Faire of the 1920’s I might add…

And can be overturned…but herein lies the problem…it can only be overturned by catastrophic economic collapse unfortunately…whereas before Lassez Faire mainly involved the enriching of the west…now neo liberalism involves great swathes of the worlds economy…..and neo liberalism is hostile to long term sustainability.

It is the perfect analogy of the self consuming parasitic ideology.

Self consuming because it actually feeds upon itself as it practices its scrooge capitalism.

Parasitic because it involves consuming the consumer by denying that consumer the very ability to consume the goods it creates…foolishness exemplified.

The wisdom of Ford was in part his great success…also…his proximity to being directly at the USA markets was another…

However – we also have had large company’s here in NZ with the same advantage in being able to offer good wages to its workers to produce a product affordable to the workers… but what happened?

The free market ideology of the neo liberal hijacking in 1984….soon changed this with these company’s going offshore for ever cheaper sweatshop wages …to avoid tariffs, union award rates , and regulatory practices…

And the laughable thing?….

Many of these iconic NZ company’s came unstuck and were eventually bought out by overseas concerns…and thus became foreign owned …as well as diminishing this country’s domestic manufacturing base.

And creating more unemployment here.

These company’s would have been far better off to ignore the neo liberal carrot dangled before them and carried on under the social democracy we once practiced and did as Henry Ford once did…

Simply make products that the workers could afford simply by paying their workers a realistic wage proportionate to the times they were living in.

Now that is a shrewd way to conduct a business.

But then again ….wisdom never changes no matter what age we live in , …..does it.

I’m not sure it’s going to take a catastrophe. I think people are waking up. I believe there is a chance we can change things with democracy.

I think every Hoskings column in the Herald probably creates 10 new socialists, we just need to give them something worth believing in.

Corbyn, Sanders, And now Sue Bradford

This is worth watching :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Pq-S557XQU

Or if the link doesn’t post, search for “Humans need not apply”

Search for a youtube video called “Humans need not apply” for a more “lifestyle cost of automation” analysis.

This film is far more comprehensive in terms of the threats that technological unemployment poses.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5twaJeq0uw&list=PLw-8zz6_M3J7A3_zGC0tFQMSQGe8SyK_o

So people think that Sky Net which is the artificial intelligence from the movies Terminator is not real but still some way off in the future?

NEWS FLASH: artificial intelligence runs Google and the U.S strategic nuclear deterrence and with increasing pace military drones.

There are also plenty of studies and news reports about high frequency trading bots. Computer algorithms designed to make trades on every exchange on the planet. Bots are responsible for 90%+ of all trades. They speak to each other and funnel investment into tech stocks. Look it up, it is these bots investing in automation. In a rudimentary sense these bots are talking to each other.

What’s worse is traders design bots to produce there own articles with which to post to Internet blogs and social media in order to recorde the number of hits, likes and comments. Then makes trades based on the data.

Sky Net is! Real.

Obviously these machines have no need for money, a point I’ll come back to. But. They still work even if these bots have no natural predators. Any species introduced into a foreign environment with no natural predators grow to overwhelm the ecosystem. Make no mistake bots are a species.

But what is the one economic factor that drives a species to overwhelm native species? It’s the idea of energy being priced at zero. Said in another way when an introduced species has no natural predators the idea of harvesting food becomes free, they don’t have to watch there backs for lions or sharks, they just go about eating and f$&king. For free.

Which brings me to my point about wages. Yes wages or money is important in the since of finance, trade and trust. The idea that the amount of effort I put into producing food is the same as the amount of effort put into to the chair I want to trade for. To mitigate seasonally adjusted imperfection we created alternate means of setting prices then coined them. Still based on trust. That system is fine when the ideas of energy sources use up whole forests or frakes the land so hard it’s toxic. Then there is a high price to pay.

If energy was priced at zero then the ideas of human interaction become free. There would be no need for wages. The idea of accumulating objects and extracting resources becomes a wast of time and effort. People would want to improve. They would want to be explorers with the skill sets and intelligence of astronaughts to be good human beings. And we would all work towards that, they would want to be captain. This is not socialism because statues still has value. Your rank and you accumulation of skills means your resource allocation is higher than cooks.

What drives these realities is energy priced at zero. Renewable energy sources like the photoelectric cell wind and solar are rapidly approaching zero. Which leads me to believe what I describe is accurate.

I like the term “Scrooge Capitalists”. More people today will think of Donald Duck’s uncle than Dickens’ Ebenezer. Perhaps that’s a good thing if they can be laughed into oblivion, but I doubt laughter will be enough.

You haven’t figured out yet that there already isn’t enough work for our workforce? That’s why we need to produce more than we need to then export. Once the developing nations are developed there really will be a massive over-supply of labour.

That’s a valid point. Under present circumstances as the jobs disappear we end up with ever more poverty. This needs to be addressed and it can’t be under capitalism.

Which is probably the main reason why capitalism brings about such uneconomic results. Cars and climate change are a great example.

One good example of a needed return is penal rates. This helps share the available work around. In this day and age we should be setting that to about 32 hours per week and four day weeks.

Keith wrote:

>> It’s a misguided concern, because its premise is that there will not be enough work for our workforce in the future.

It’s a bit like being concerned that we will not have enough pollution in future, and certainly more pollution creates more work; so, more pollution must be a good thing. Yeah right? <> We saw such a crash in 2008 with the temporary cessation of sub-prime lending <<

This is a footnote I know, and the main thrust of your article doesn't depend on it, but another economist, Jeff Rubin, claimed in his book 'Your World is About to Get a Whole Lot Smaller' that it was the spiking of crude oil prices that triggered the 2008 crisis. According to Rubin the oil price spike caused the tightening of credit worldwide, leading in turn to the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US, but other equally catastrophic economic effects in other countries. Any comment on this?

That comment got a bit mashed. Is it possible for mods to remove the >> << marks, and replace them with "" ?

I think AI the movie is amazingly prophetic actually, it seems to be looking more and more realistic as the future of Earth and robots unfolds. Truely a remarkable movie for it’s time.

http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/ai_artificial_intelligence/

Comments are closed.