Headline: Dean Parker: Let’s remember the martyrs on May Day

The fight for workers’ rights has been a long and bloody one, with deaths on both sides of the political divide.

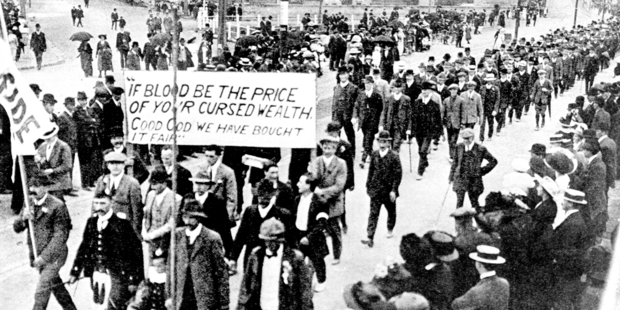

A striker’s march in 2013

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Go down to the Queen’s Wharf on the waterfront and you’ll see the beginnings of a heritage trail with cut-out effigies of figures from the past and background information.

These figures are described as “Lovers of Auckland”, Tamaki Makaura, Tamaki of a Thousand Lovers.

It’s a catchy theme for a heritage trail but problems arise when dealing with major historical events of waterfront history. Such as the strike of 1913.

Last year the trail included, as one such lover of Auckland, the figure of a 1913 Police Special together with a plaque saying, more or less, that this bloke loved Auckland so much he came down to the wharves and beat a whole lot of other Aucklanders’ heads in.

Following reservations about the wisdom of this, the 1913 exhibit was removed and never replaced.

Today being May 1, May Day, International Labour Day, it’s worth remembering a similar attempt elsewhere to commemorate one side of history, the bosses’ side – and the consequence, and all of it rooted in May Day history.

If you’re ever in Chicago, head west on Randolph. You’ll cross over two arterial routes, the river and then the thick cordage of midwest railway lines. Just as you reach a third artery, the Kennedy Expressway, pull up. You’ll be in a bleakish urban clearing of concrete surrounded by characterless offices and warehouses.

There’s a pedestal there. It’s a bit knocked about, but evidently once served a purpose. If you approach and bend forward, you’ll see inscribed on it, “In the Name of the People of Illinois I Command Peace”.

But there’s nothing there commanding anything. The pedestal used to host a2.7m bronze statue of a 19th-century Chicago policeman with a raised hand.

The bronze policeman had stood there, firm and unyielding, until 1927 when a Chicago street car driver deliberately jumped the rails and rammed his tram into it.

It was re-erected and stood on its pedestal for four decades until, in 1969, it was blown up by the urban guerrilla group, the Weathermen. It was replaced and blown up again.

A suggestion was made that the Chicago City Council investigate having a series of duplicates made out of fibreglass so as each was blown up it could be the more easily replaced.

This was opposed by the Mayor who wished the statue restored in its original bronze. The Mayor had his way, but a 24-hour police guard was engaged.

After 12 months the bill for securing the statue had reached US$67,440 ($78,800).

Rather than expending further civic finance, the council came up with a novel cost-cutting alternative. Instead of bringing the police to the statue, the statue was brought to the police, removed from its pedestal and placed in the lobby of the Chicago Central Police Headquarters.

There it remains.

The genesis of the bronze policeman was a period of international labour agitation for an eight-hour working day: eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest.

Nineteenth century Chicago had been the centre of that agitation.

In May, 1867, 10,000 union members had marched through the city and struck for the eight-hour day. Some employers caved in. Most took advantage of a time of unemployment to bring in jobless from out of town. The strike was defeated.

Twenty years later the eight-hour day movement was again a force.

Meeting in Chicago, the Federation of Organised Trade and Labour Unions of the United States and Canada resolved, “That eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labour, from and after May 1, 1886”.

The date may have been chosen to commemorate the May strikers of 1867, but just as likely is that the delegate who sponsored the motion, a carpenter, figured the beginning of spring would see the building trades back in business after the winter lay-up and more willing to settle.

Nationwide a total of 340,000 workers struck on May 1, 1886, a Saturday. Almost a quarter of those were from Chicago.

In the world’s first May Day parade, Lucy Parsons, a labour and women’s rights speaker, together with her husband Albert and their two children, led 80,000 Chicago workers up Michigan Avenue, arm-in-arm, singing.

The following Monday, 200 eight-hour day supporters marched to the McCormick Reaper Plant (now the International Harvester Company) to join a picket. Chicago police under orders of a minion of Cyrus McCormick II – of McCormick Reaper – turned up and fired on the crowd, shooting two men dead.

Next day 2500 protesters gathered in the evening near Chicago’s Haymarket Square to condemn the shootings.

Waiting were 176 armed police. This time someone got the retaliation in early and threw the first-ever dynamite bomb, killing one policeman and injuring others.

The police immediately fired back, killing four and wounding 20.

The leaders of the protesters were rounded up and four hanged. One was Albert Parsons.

Two years after the Haymarket deaths a Chicago businessman put up $10,000 for a statue to be erected in the square to commemorate the police action.

The statue was sculpted: a policeman with raised hand and the inscription, “In the Name of the People of Illinois I Command Peace”.

The policeman who modelled for the statue was later removed from the force for trading in stolen goods.

In 1889, in Paris, at a meeting of the International Labour Congress celebrating the centenary of the storming of the Bastille, a delegate from the American Federation of Labour requested that May 1 be adopted as International Labour Day, upon which the working class would march for the eight-hour day, for democracy and the rights of workers to organise – and would remember the labour martyrs of Chicago.

And that is how workers come to celebrate May 1, and how there is a bronze statue of a policeman, arm upraised, in the lobby of the Chicago Central Police Headquarters, a warning to all about taking history lightly.

Dean Parker is an Auckland writer

– NZ Herald

—