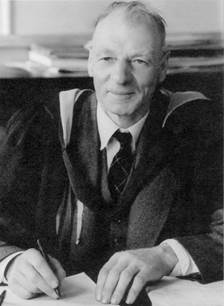

Andrew Davidson: Schoolteacher; architect of New Zealand’s welfare state; the third of “The Three Wise Men of Kurow”)

HOW COULD I have forgotten him? The third wise man of Kurow? I can only put it down to my lamentable, political commentator’s, habit of seeing the parliamentary world as the be-all and end-all of politics. If anybody has ever proved how mistaken that viewpoint can be, it was the headmaster of Kurow School, Andrew Davidson.

In the early 1930s, in that little North Otago town, Davidson worked every bit as hard as his two good friends and colleagues: Arnold Nordmeyer, the local Presbyterian minister, and Gervan McMillan, the local GP.

Thanks largely to the 2,000 construction labourers and their families who had moved into the district to work on the Waitaki hydro-electric power scheme, the number of pupils attending his little school had swollen from 63 to 339. That would have been enough to keep most people busy, but Davidson felt morally obliged to do more. Like Nordmeyer and Girvan, he had been shaken by the suffering of the Great Depression: suffering that had penetrated all the way to Kurow; all the way to his classroom.

The artist and writer, Bob Kerr, has recorded it all in his wonderful book The Three Wise Men of Kurow, and on his blog, Undercoat. If you visit the latter you’ll read about Bob’s trek up the narrow Awakino Valley to a place called “The Willows”:

“It was here [by] the Awakino Stream that over 350 unemployed men and their families set up the Willows Camp during the worst years of Great Depression of the 1930’s. Many of them would have walked up the valley from Oamaru and finding there was no job they would have waited at the Willows rather than make the long trudge back down the valley.”

One should bear in mind that this was inland North Otago: stinking hot in summer; freezing cold in winter:

“The hills on either side of the stream would have protected the squatters from the worst of the freezing westerly winds but they would also shade the valley and winter frosts would have remained for weeks. Local legend has it that ‘whiskey froze in the bottle and nappies hung like boards on the line.’”

Whole families lived in canvass tents or in “shacks made out of willow branches and beaten out fuel cans”. These are the sort of conditions we associate with reports of poverty in the Third World. But during the Great Depression, shacks and tents were as close as thousands of New Zealanders came to a home.

Bob writes on his blog that Davidson, McMillan and Nordmeyer “were soon in regular contact with the families at the Willows. It set them thinking. The three wise men, as they were affectionately called, were appalled at the squalid living conditions.”

In a vivid series of watercolour sketches, Bob depicts what he calls “The Conversations” that took place at McMillan’s house. It was out of these, the intense discussions of three socially conscious and politically committed young men, that the policy remit which McMillan took to the 1934 Labour Party Conference was drafted. That remit would provide the bones of Labour’s 1935 manifesto promise to construct New Zealand’s welfare state. In 1938 its six key policy points, distilled out of countless conversations around Girvan McMillan’s dining room table, became the basis of the First Labour Government’s Social Security Act.

It is worth quoting the Act’s title in full:

“An Act to provide for the payment of superannuation benefits and of other benefits designed to safeguard the people of New Zealand from the disabilities arising from age, sickness, widowhood, orphanhood, unemployment, or other exceptional conditions; to provide a system whereby medical and hospital treatment will be made available to persons requiring such treatment; and further, to provide such other benefits as may be necessary to maintain and promote the health and general welfare of the community.”

In 1935, to make sure their innumerable conversations bore fruit, Andrew Davidson’s mates, McMillan and Nordmeyer, were both elected to Parliament on the Labour ticket. But the Kurow schoolteacher did not join them. In the years after 1935 he devoted himself to education, ending his career as the Principal of Macandrew Bay Intermediate School.

Along with Nordmeyer and McMillan, New Zealanders owe Andrew Davidson a huge debt of gratitude. Who knows what it was about Kurow and the broad Waitaki Valley that made it, for a few extraordinary years, a crucible of radical thinking. Who can say why three young men together decided that from this isolated spot, in the farthest reaches of Britain’s vast empire, a blueprint for social change could be drafted that would, for the next 50 years, make New Zealand the envy of the world.

I am sure that it was of people just like Andrew Davidson, the third of Kurow’s three wise men, that Margaret Mead was thinking when she wrote:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Want to support this work? Donate today

My Grandfather was one of the workers who descended on Kurow, he was a cook for the road gangs and got traded to the hydro workers in a card game.

He was a small fellow, just on 5 foot, and couldn’t do any of the heavy lifting and hard labour that was needs. He was however, a talented cook who could stretch a meal to feed many more mouths than he was officially cooking for. He was also a talented thief, hunter and a shocking womaniser.

He worshipped Arnold Nordmeyer and everything the labour party had done to improve working peoples lives. He had 7 children, 1 of which made it to university – An achievement he was proud of, as he left school at a very young age. Of his grand children I was one of many who attained higher education.

The dams and civil works jobs meant he was able to make a living and have a family – The grand public works were something he was proud of and proud to have been a part of. I remember as a kid always stopping at some such place were he’d been the cook. Roxburgh dam was his favourite job, as it was the first job, when he could buy all and any of the raw ingredients he needed to cook for the crew.

I think he would be rolling in his grave to think all the achievements to improve the lot of the average kiwi has been rolled back. He was a simple man, of simple pleasures – and he hated when people were not able to eat. He understood what deprivation and hunger meant, especially for children, it was this lack of nutrition and decent food at an early age which meant he was so tiny and he had health related issues from this, which eventually killed him.

Thanks Chris – that was a joy to remember all that stuff.

Thanks for this Chris. You’ve reminded me that my Dad was at the Willows camp in 1931 or 32.

As a twenty or twenty-one year old tramp he’d walked there from Picton, having heard there was work at Waitaki. He arrived starving and with frostbite and stayed awhile, doing meaningless chores assigned by the ‘ganger’ – thereby assuring he would be fed. It was a critical time in my Dad’s political education and though he didn’t become a parliamentarian he spent many years as a leading trade unionist and left-wing activist.

We need reminding of this history and the legacy we betray.

The Wellington theatre group The Bacchanals are touring a play next year, election year, about the creation of the Waitaki dam and the 1938 Social Security Act. Play is entitled ONCE WE BUILT A TOWER. (Title comes from that great depression song, BROTHER CAN YOU SPARE A DIME: “Once I built a tower to the sun / of brick and rivet and lime / Once I built a tower, now it’s done / brother can you spare a dime…”)

Comments are closed.